“Do you have any discomfort about aestheticizing nature for your art?”

– Adeline Chia

On the evening of 22 May 2020, Mizuma Gallery hosted our first-ever online Artist Talk in conjunction with our ongoing exhibition “The Seeds We Sow“. This live panel discussion featured the four exhibiting Singaporean artists: Ang Song Nian, Marvin Tang, Robert Zhao Renhui, and Zen Teh, in conversation with independent writer and editor, Adeline Chia.

If you missed the chance to join us, fret not – a recording of the discussion is now available for streaming! You may watch the video, listen to the audio recording on our podcast, or read the transcript by clicking the links below.

Watch the Video:

Tune in to the Podcast:

| |

| |

___________

Adeline Chia: Hi everyone, my name is Adeline Chia, and I’m the reviews editor of ArtReview Asia. Welcome to the talk. I’m an independent writer and editor, but I would like to make it clear from the start that I do have some relationships to the speakers on the panel, friendships with some of them, and my partner is Robert Zhao. Hence, I have a closer relationship to the material as well as to the people, so I hope that this can be a more informal and illuminating chat.

The artists are part of a group show called “The Seeds We Sow” at Mizuma Gallery, which has been extended to July 5. But the gallery is closed and you can’t actually see the show, so I hope that this will be a good proxy experience.

Some ground rules first: If you have questions during the course of this panel discussion, please type them in the chat window, and then we’ll look at them in the last 15 minutes of this session.

My first question is to all of the artists. Besides being in the medium of photography, all of your works bear a relationship to nature. That is the overarching theme of the exhibition. I would like all of you to give a brief introduction to the works being shown in the exhibition, and to share what specific relationship or aspect of nature your work explores.

Let’s start with Song Nian?

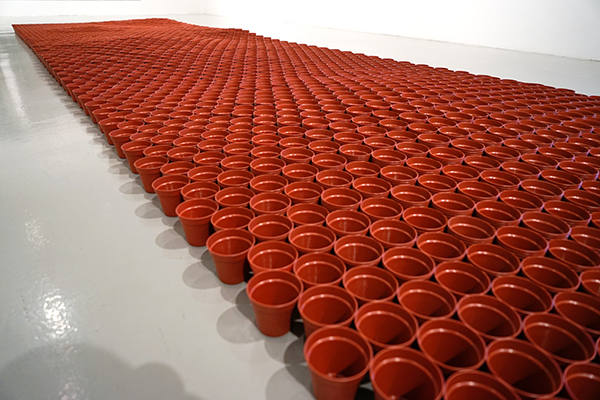

Ang Song Nian: Hello everybody, thanks for taking the time to join us this afternoon. In this show, I’m showing two bodies of work. One was made in 2016-17, an ongoing photographic series called As They Grow Older And Wiser. The second is a site-specific installation, Artificial Conditions, a work that was made late last year as part of a solo showcase at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum last November. I see the installation as an expansion of As We Grow Older And Wiser, which was started in a residency I did in Bangkok. There, I observed that all the new properties were adorned with a lot of potted plants. That led me to look at the way we were planting and incorporating plants into the urban landscape.

Exhibition view of As They Grow Older And Wiser and Artificial Conditions by Ang Song Nian at “The Seeds We Sow” at Mizuma Gallery, 2020.

I visited many nurseries in Bangkok. In my work, I wanted to provide an experience where we feel like we are walking into a natural environment, when in fact, the images we’re looking at are all manipulated and taken within plant nurseries.

Moving onto the installation. It consists of 10,000 biodegradable plant pots. This work came out of playing with familiar materials in plant nurseries. I felt that the plant pot is a synonymous with the relationship we have with plants. I was also playing around with the idea of landscaping. We convert what is natural into what is manmade, and then repurpose that into a landscape to convince ourselves that what we’re seeing feels very natural. My installation repurposes something that is manmade to create the look of a terrain. In the gallery, you can see very gentle and subtle [sloping] terrain that is being formed by the arrangement of the pots.

Marvin Tang: The work I’m showing in this exhibition is called The Colony Archive. It’s part of my research when I was doing my Masters in London, where I looked at Kew Gardens and its association to Singapore Botanic Gardens. More broadly, I was looking at how botanical gardens were formed across colonies, and why they were such important institutes in the colonies. During that time, I also stumbled on postcard fairs in London. There was this huge postcard fair that would happen every month, and that was where I started collecting postcards. There was a huge collection of Southeast Asian postcards (sometimes called the “Far East”) of botanical gardens. I realized that there was a visual similarity across the various gardens, whether in Singapore or Kandy, Sri Lanka. As I started trying to understand the purpose and agendas of these postcards, The Colony became a larger project where I explored how botany has changed our living environment and its impact on individual countries.

For this exhibition, I’m showing The Colony Archive, comprising a series of postcards created by me, as well as archive postcards I found along the way, putting them together to create a cohesive single botanical garden called The Colony. This is the first time I’m showing this work. In the future, I’m hoping to expand the number of botanical gardens you see in this installation.

Zen Teh: My work is titled Reclaimed Sculpture: Domestic Landscape. Recently I just started working with refurbished furniture sourced from second hand shops—this cabinet is from Carousell— because I wanted to make my practice more sustainable. My work involves a lot of found objects that are repurposed and, in a way, upcycled. The work in the exhibition talks about the idea of the domestic, in the sense of an interior space, as well as the mindscape of the artist. The nature motifs that you see in the different sides of the cabinet—some were already existing, others I added. If you open the different drawers and compartments, you see different motifs and scales of nature. Some show potted plants, for example. At the very top of the cabinet, you see a longing for larger landscapes and finally the mindscape of the artist.

This work was created during the Covid-19 period. Like all of us, I’ve been homebound. The different motifs and scales of nature represent the different yearnings toward different scales of nature that we have.

Adeline Chia: The decorations on the cabinet, you painted them? Or it was pre-existing?

Zen Teh: The motifs on the cabinet were already there. I refurbished and, in the parts, where [the paintings] were not so clear, I improved on them.

The lightboxes are created from scratch, and the images are local images. Some images are of landscapes close to my place, and others are from other nature reserves and parks.

My work has a strong Chinese landscape influence. The idea of the landscape being a representation of the emotion and the inner landscape of the artist is something that I borrowed from the Song Dynasty landscape painters. I show different scales of nature and in some images, embed people in them so you see the scale. Some of them are more daunting and some are quite unclear. In the image in the top drawer, part of the cliff is hidden in the fog. This is inspired by Liang Kai’s painting. He was a painter in attendance in the Song Dynasty Imperial Painting Academy and well-known for his paintings that are influenced by Zen Buddhism.

Robert Zhao Renhui: These images were taken in secondary forests in Singapore. Secondary forests are forests that have regrown from forests that were disturbed by man. Unlike primary forests, which are older and have more vulnerable ecosystems, secondary forests are very new, made up of invasive species. We have a few of these secondary forests in Singapore. They are not protected and are in an in-between state of “not being developed” and “waiting to be developed”. Meanwhile, nature takes over.

These forests are not planned. They are a different kind of nature from the greenery seen along the streets. Singapore is very green, but a lot of the greenery is made for humans in mind. Cities are made for humans, understandably, so that’s why all these green spaces are mainly for our enjoyment. They are low-maintenance and contain species that are for pure aesthetic reasons and have zero ecological use for non-humans.

By going into the secondary forests, I’m trying to find a way to look at non-human species and their presence on our island.

Exhibition view of Laughing Thrushes, Scolding and Monitor, Swimming by Robert Zhao Renhui at “The Seeds We Sow” at Mizuma Gallery, 2020.

I use photography a lot. It allows me to have a different sense of time with nature. These images were taken with heat and motion sensor-triggered camera traps used by scientists. These images are in sets of four, in a timed sequence, from a movie clip. Almost like in an Eadweard Muybridge time sequence, you can see animals moving from left to right, or going in and out of things. This is my seemingly objective study of animals going about what they do in a manmade landscape.

Adeline Chia: Thank you everybody for sharing. Some of you actually touched on this, but I want to go into it a little deeper. As Robert mentioned, there is a certain quality of photography that helps to bring out certain themes in your work that is specific to the medium. Robert mentioned that photography allows him to capture time (his is a timed sequence of images). Could the other artists share what about photography is relevant to the ideas that you’re trying to investigate?

Ang Song Nian: Those of us who own potted plants like to see it grow from a seed into a seedling. Photography allows me to, I wouldn’t say freeze the process, as plants grow very slowly, but to capture the plant at a particular stage of its growth.

During my Bangkok residency, I had to go back to the nursery multiple times. I was able to witness how vastly different the plants look within one- or two-weeks’ time. With potted plants at home, you see the plant in the morning and the evening, and you’ll be able to see it moving towards the sun. If you flip it around, the next day it will go back and lean towards the sun all over again. The whole process becomes more meaningful if we can witness the stages of growth.

Adeline Chia: So, you’re saying that photography is a record. In your work, there is also a play with the sense of scale. Why the work is interesting to me is that it looks like a forest, but actually when you look at it more closely, it’s a very cropped view of nursery plants. Do you consciously play with different scales and the “real” status of the photograph?

Ang Song Nian: The decision of the dimensions and the scale was influenced by my experience of going to the nursery when I was young. My father used to take me to plant nurseries not to buy, but just to look. Walking among the taller plants felt like I was stepping into a forest, and that was the experience I wanted to recreate in this series.

Adeline Chia: Zen mentioned the influence of the Chinese classical painting tradition, where landscape is a representation of the interior mind or mood. Could Marvin share more about the use of another genre, the vintage postcard, and your interventions into this tradition?

Marvin Tang: To look at postcards, you need to look at the history and the content in them. Postcards started featuring photography 60 years after the invention of photography. I’m interested in the 1870s to 1900s, the Victorian age of exploration. Postcards became an easy and accessible way for people to collect the world. A writer who talks about the archive, Ernst van Alphen, he wrote in his book [Staging The Archive: Art and Photography in the Age of New Media] that photography and imperialism would meet and collaborate. For example, you’ll see an image of a cluster of tribal men standing together. Postcards became a symbol of the exotic, a way of bringing in the exoticness that they can only imagine or read through books.

People were interested to see what the colonial powers were doing outside of the country. From Singapore, you see pictures of the Raffles Museum, Raffles Institute, Botanic Gardens. That’s when you realize that it’s not just the landscape people are interested in. They are interested in the institutions.

Postcards also blur the line of where the image was taken, they blur the line of the providence. For example, when I was collecting the postcards, I have postcards with stated origins of Japan or Indonesia, but they are actually the image of the Singapore botanical gardens. This ambiguity in postcards is actually very important as well.

Adeline Chia: In your work, I sense the complicity between imperialism and knowledge, specifically botany. You mentioned you wanted to create a singular garden, which speaks about a certain homogeneity in the colonial imagination, in trying to recreate the same idea in different places. Is this what you’re trying to get at?

Marvin Tang: Yes, if you talk about gardens and their similarities, you need to think of the gardeners. Who’s governing the space? A lot of gardeners who were in charge of botanical gardens across multiple colonies came from Kew Gardens. For example, Henry Riley, who was in charge of Singapore Botanic Gardens was from Kew, went to Calcutta to do his research and then came to Singapore. A lot of tropes in British gardening were carried forward into many colonies. In the Singapore Botanic Gardens, you’d see symmetrical patterns, and then later on, the British were very interested in an asymmetric style, and you’d see that being transferred into other botanic gardens.

Adeline Chia: In this installation, you include actual postcards and as well as ones you invented, featuring these tropes that you mentioned?

Marvin Tang: Yes. Also, the interesting thing for me is that when you go to these Botanic Gardens, plants from different regions may be presented in the same space. They form what I think of as impossible landscapes, things that would not occur in the wild, in first hand nature. Being put together, my collection of postcards, creates this feeling.

Adeline Chia: An interesting contrast to Marvin’s and Song Nian’s work is Robert’s work. Marvin’s and Song Nian’s work is about a very manicured and controlled version of natures, domesticated or colonized; whereas Robert’s work is trying to capture a bit of wilderness in a place that is not very wild. It’s trying to do the opposite, capturing a part of Singapore that is undisciplined by urban planning or human intervention. Can Robert share the thought processes behind your work?

Robert Zhao Renhui: I’ve been trying to document nature in Singapore for some time, which is extremely difficult to do. If you go to the forest with me before, you will know that nature is very boring. There’s nothing happening, just a lot of trees, mosquitoes, humidity—these are the first impressions of stepping into a tropical forest.

As an artist, I ask myself, how can I contribute another perspective to think about nature? We have so many nature photographers. Everyone has a camera. There are so many beautiful pictures of nature in Singapore. How do I contribute a different lens and viewing experience? I’m not interested in going out there, hunting for beautiful species with a large lens. This kind of photography has its own use, but what other kinds of dialogue can I open up?

That’s why I started doing walks in the forest. It enables me to take people to look at nature directly. I also started doing photography without me. As many as 50 of my cameras are inside the forest, and I just let nature do its thing. When it rains, or a leaf moves, a moth flies through, an image will be captured. After one year of doing this, I realized, “Oh my god, it’s so boring.” There are some things happening, but also nothing. Then I realized this is what nature is about. It doesn’t perform a drama, like an eagle eating a mouse, otters eating fish, the kind of nature we see in National Geographic. Nature doesn’t entertain us.

At the same time, every forest and landscape has a story in it. The patch of forest near your house is different from the one near my house. And all the species of the plants inside have their own history, history of our land use, for example. And even the birds there, they are the same species, but they behave differently from those in Bukit Timah. I’m trying to understand how each species of plant and animal are individuals in their own right. We need to take the time to enter the zone where it’s slower, more historical and personalized.

Adeline Chia: I think it’s interesting what Robert touched on, about capturing a different relationship to nature. You use motion sensor cameras, which translates to almost relinquishing authorial control, in a way, and avoiding imposing any order, aesthetic or framing onto the work. I want to pose a question to all of you: what is your comfort level of aestheticizing nature for your art? One of the questions that has been asked is how is your work complicit with the colonial imagination, which separates culture from nature very distinctively. My question is more formal: Do you have any discomfort about aestheticizing nature for your art? You could also share about the other strategies that you use.

Robert Zhao Renhui: I try to steer away from any colonial ways of engaging with or thinking about nature. A lot of science is like that, and I work with science; yet precisely because I’m not a scientist but an artist, that I try to steer myself away from that. Photography lends itself to the impulse of trying to capture and to take things away. That in itself is very colonial, the urge to amass something.

I think what my peers and I do is that conceptually, we try to resist the urge. It’s not a pure aesthetic experience that we take away from nature. Okay, it is aesthetic to a certain degree, at least, but speaking for myself, I try to avoid exoticizing the subjects. I try to give them a sense of unknowability. And I’m not trying to glorify them as a trophy. Nature photography tends to have a certain narrative and an approach similar to hunting, almost. I think none of us in this exhibition would do that, going out to collect trophies. We are trying to talk about different ways that we have messed up historically or in a contemporary sense.

Zen Teh: For me, the images are a composite of my travels and interactions with nature. They are collaged together to form another experience, a larger landscape than the human-centric point of view. It has more of an Asian, Eastern, or even Chinese point of view, of how we are smaller than nature. In the discussion so far is a Western point of view where human control nature. It’s not how I see nature. I see it as an experience that I would like to share in different ways in my work.

Adeline Chia: Let’s take some questions from online. This one is from June. How has the circuit breaker changed the way you work, seeing as a lot of the work involves going outside? Has it made you more investigative of your internal world?

Zen Teh: For me, it’s quite obvious. More than any other work I’ve created, this one is more about my reflections at this stage of life and the challenges I face. I wanted to create an inner mindscape that everyone can relate to and interpret it in their own way.

Ang Song Nian: It hasn’t really changed the way I work. I’ve just not been producing. [laughs]. We’re being dealt a pandemic and a lot of artists feel the pressure to keep on producing. I don’t think we need to feel the stress because these aren’t normal times. Having said that, I’m spending more time on research. Right now, I’m preparing for a work I can’t make yet. The situation forces and encourages us to slow down and read more, look and observe more.

Marvin Tang: I think what Song mentioned is absolutely right. There’s an inherent pressure to deliver. I’m supposed to be doing a residency now, which is quite impossible. It turned into a home residency. It is a good time not thinking about how the work will look like, but gathering the information first and getting a sense of where it can go.

I know digitalization is a buzzword right now, but the reality is that the pandemic really forces you to think how your work can exist on different platforms.

Adeline Chia: Anne Lim asks: “Looking at nature as a construct of humankind, and more specifically, the colonial logic of hierarchies that are human-centric, how do you think your work push against or are complicit with the colonial dichotomy of man and nature?”

I think Robert did address it a little in what he said. He uses camera traps and portrays nature as unknowable instead of using it for making an aesthetic image, or collecting it as a trophy, as he says. This question also refers to Marvin’s and Song Nian’s work. It addresses the domestication and control of nature. Could both of you share your response to the question?

Marvin Tang: Let’s start from how plants have been moved around to create gardens. In colonial times, when they were trying very hard to move ferns from Australia to the UK, they ended up coming up with a technology called the Wardian case to move plants, which became a way to domesticate plants. The Wardian case is the precursor to the terrarium today. Our modern relationship with plants involves having them around for decoration and fulfilling a psychological need. In the post-colonial period, we are still experiencing the impact of how plants were moved around. In Singapore, we see Brazilian rubber trees in our sidewalks, for example.

Adeline Chia: I feel that because your work is positioned as an artwork, it doesn’t aspire to capture any so- called reality that the creators of the postcards tried to capture. And of course, your agenda is very different to theirs. Your approach is more open-ended and searching, it’s imaginary, you’re constructing a new narrative out of the old narratives. So there isn’t such a direct hierarchical relationship between you the artist and nature per se. You are working with the mediated images of nature.

Song, any thoughts?

Ang Song Nian: Every time I’m back in the nurseries photographing, I can’t help but think of bonsai plants. To me, bonsais represent the degree to which we are manipulating, controlling and designing nature. I don’t know whether my work counts as being against or complicit with the dichotomy, to me it’s really just an honest reflection of what’s really happening.

Adeline Chia: I feel you flip the dichotomy around a bit. You are using the manmade objects of the pots to create a “natural-seeming” landscape. Maybe you relish the fact that our relationship with nature is so corrupt and fallen that this is what constitutes as natural right now.

Ang Song Nian: That’s what I gathered working with the potted plant industry for several years. The potted plant starts off as natural, and then we commodify it, and then we mass produce it in landscaping. My installation with the plant pots reverses that flow.

Adeline Chia: There’s a question for Zen. Does she plan to move in the direction of the new work and to create similar installations? Is there a reason for the choice of Song Dynasty for her inspiration?

Zen Teh: I will continue to make work using found or repurposed furniture or objects. That is in line with the development of my work as an environmental artist. Personally, I love nature and I love plants. One day I can show you on Instagram the hundreds of plants I have on my balcony, and I’m still greedy, trying to get more. It’s my lifestyle and personal passion. That’s how nature fits into my life. In my show in September at NDC [National Design Centre], I will be working with familiar materials such as native plants, moss and weeds.

As for taking the Song dynasty as an inspiration: Early on, in the Tang Dynasty, a lot of artists responded to the political situation by retreating into nature to find their sense of identity and to communicate the distress they faced in their lives. Their art was still a description of the visible world, and they represented their ideas through images of nature.

In the late Song dynasty into the Yuan dynasty, painters started to look at paintings as extensions of themselves. The paintings described their mindscapes and their thinking about life. That’s why there was the influence of Buddhism and Taoism present in their work. But that religious component is not there in my work, which involves more of a spiritual journey into nature.

The sense of travel in Chinese painting is very apt in my work, because you journey through a landscape of different scales in the different images and different parts of the cabinet.

Adeline Chia: Zen’s work also raises an interesting framework because it’s influenced by an Eastern view of nature, which on one level, shows the interiority of a person, on another level, and how humans are minuscule in scale compared to the larger universe.

One of the questions I wrote down and I didn’t get to ask is: What kinds of alternative conceptions of ecologies can art propose?

Robert Zhao Renhui: There is a common thread in our work, which is that we all fight against the urge to consume nature as a commodity or spectacle. Art can think about nature in a way that is not about consuming it. How do we have a relationship that is not pure consumption? Our works touch on different parts of that, trying to establish new positions and new ways of engaging with nature besides as a spectacle.

Adeline Chia: Thank you everyone. I learnt a lot today about your practices and the thinking behind your work.

—

“The Seeds We Sow” exhibition, featuring works by Ang Song Nian, Marvin Tang, Robert Zhao Renhui, and Zen Teh will now run until Sunday, 5 July 2020. We will announce the details of our gallery’s opening hours in due time, so stay tuned for more information!