“Wild, no hold- barred use of materials from eggshells, metal, and correct me if I’m mistaken – but I think this was the time you started to do highly elaborate performance works. This medium exploration is also parallel with your subject- matter at that time, which said a lot about societal anxiety, fear and hidden/repressed violence in relation to cultural identity, religion and faith, and politics, with striking, grotesque, theatrical visual language. Can you mention one work during this time that you regard most important, or special?”

– Farah Wardani

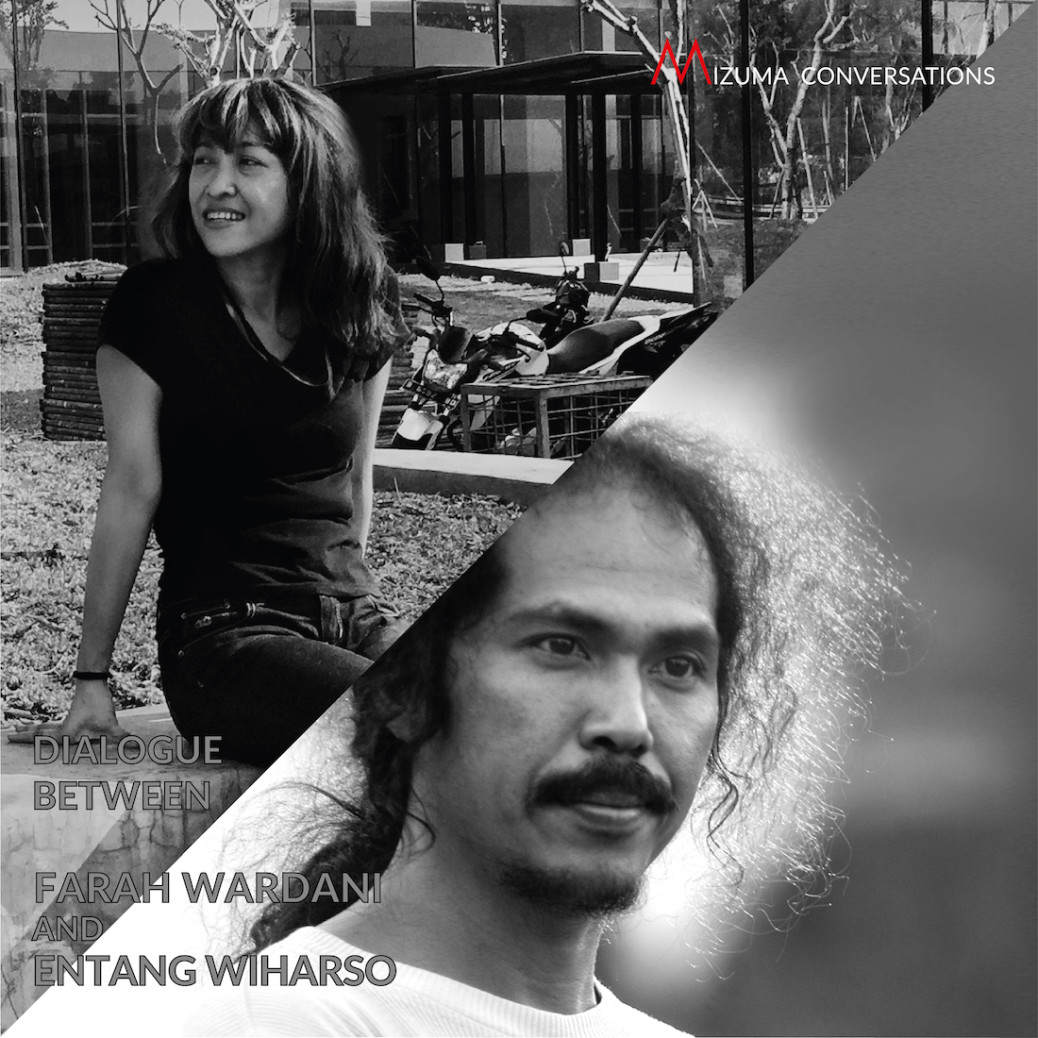

Tune in to our latest IGTV with Art Historian and Curator, Farah Wardani in conversation with Indonesian artist Entang Wiharso !

Farah Wardani completed her MA in Art History (20th Century) from the Department of Historical & Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths College, London, UK, in 2001. She has been active as a teacher, researcher, writer, curator and art organizer since 2001 in her home country, Indonesia. Her works comprise projects collaborating with art spaces like Cemeti Art House, Yogyakarta and ruangrupa, Jakarta, Indonesia. From 2007 until 2015 she was the executive director of Indonesian Visual Art Archive (IVAA) in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, with works include the IVAA Digital Archive, the first digital archive of contemporary art in the country. She is now a part of the Board of Advisory of IVAA. From 2012-2013 she was involved in Biennale Yogyakarta XII 2013 as the artistic director. From 2015-2019 she was the Assistant Director of the Resource Center at the National Gallery Singapore. She is now the Executive Director for the upcoming Jakarta Biennale 2021.

Entang Wiharso (b. 1967, Indonesia) is one of Indonesia’s most acclaimed contemporary artists and is known for creating provocative works loaded with bold visuals and distinctive imageries. Since 1997, Wiharso, his American wife, and two children have shuttled between Yogyakarta, where his Indonesian studio is located, and his studio in Rhode Island, U.S., progressively belonging and un-belonging to his land of origin. These two vastly different countries have become important parts of his identity, and this dichotomy of cultures, personal opinions, and experiences are reflected in his works. Wiharso graduated from the Indonesian Institute of Arts in Yogyakarta, majoring in Painting, in 1994. He has also been included in such major group shows in China, Singapore, France, Indonesia, Japan, United States among others. He is represented in numerous notable collections, including the Guy and Myriam Ullens Foundation, Switzerland; the Olbricht Collection, Germany; the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the Rubell Family Collection, Miami, United States; and the Singapore Art Museum. Entang Wiharso lives and works in Rhode Island, United States, and Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Scroll through to watch a video excerpt of this dialogue. A full audio recording of this dialogue is available on our podcast, and as a text transcript below.

Watch the Video:

Tune in to the Podcast:

| |

| |

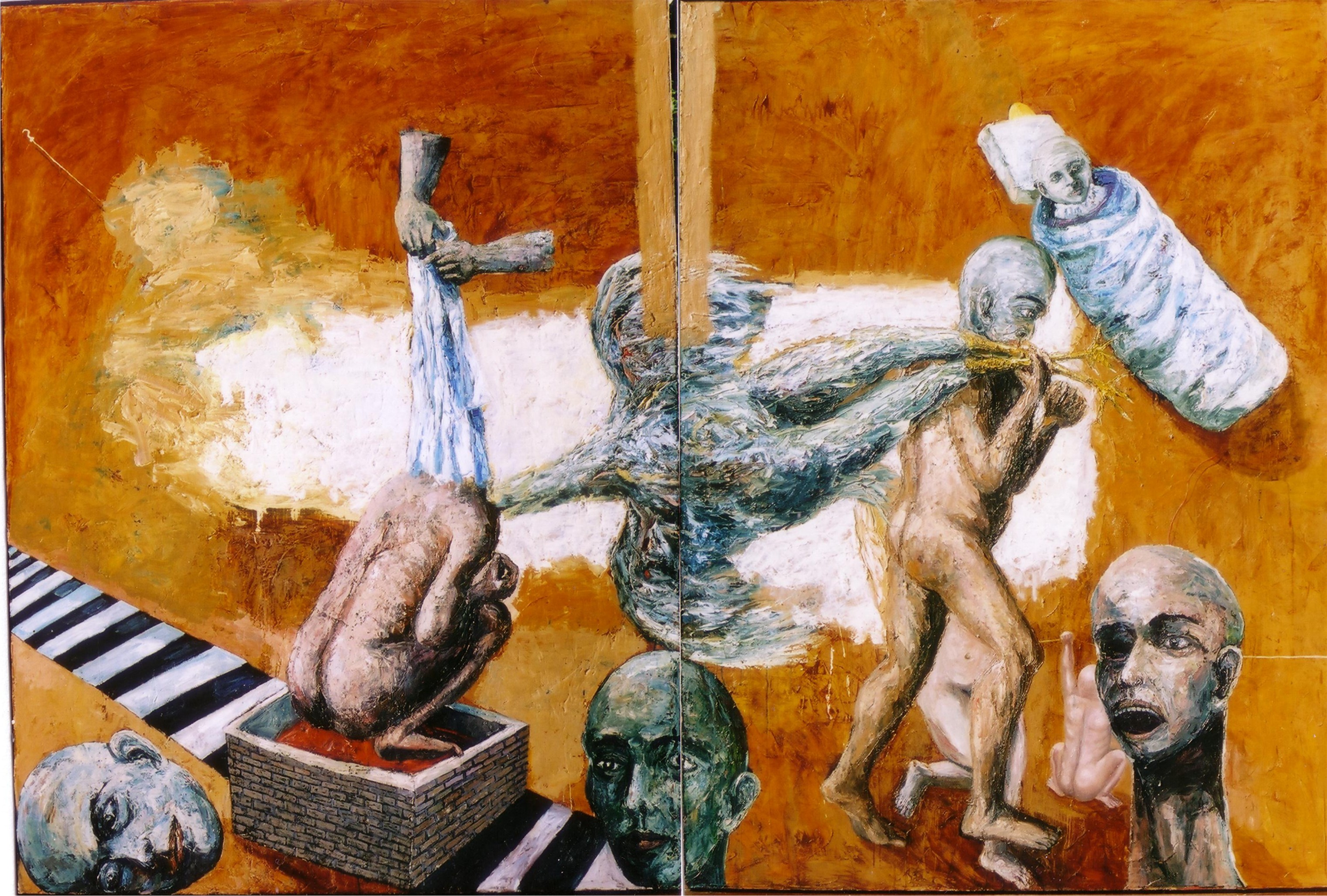

Farah Wardani (Farah): I see that 2001 to 2003 was a defining period in your journey as an artist. 2001 was your first major solo exhibition ‘Nusa Amuk’, which was a traveling show from Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and Washington, D.C. Then in 2003, you had another solo exhibition in Rhode Island, where your work Portrait in the Gold Rain (2002) was banned due to some reasons that were considered offensive for American viewers.

‘Nusa Amuk’, as well as your works during those times were somehow very relevant with the spirit of Indonesia post-1998 and it’s interesting how it resonates with the post-9/11 American audience too. If you look back, what was the most significant point in your artistic phase during this period?

Entang Wiharso (Entang): The experience that I am most aware of is how I tried to put myself in the position of being a neutral person in seeing the situation and the socio-political conditions where I was, both in Indonesia and in the United States. I remember that during that period I was on fire. I worked so hard and put all of my energy into my art to capture the psychology of that particular time and those conditions. It was constant working, rethinking and evaluating as a citizen and also as an artist.

I was away for a few years and I came back to Indonesia with my fresh eyes and my new ideas about how to create art and engage with the public. It was a fertile time with new hope. I tried to put art in a real context, as something that was given to the world as a tool, to create more possibilities, no matter the conditions. The key when I am creating art is, my art is not a measure of morality, nor a tool to document events, and it also does not contain a linear narrative in telling the suffering of people. As I recall, I tried to disassemble, to question and to evaluate the system and our mindset.

I live in two places that are full of dark and heavy history. In Indonesia, life holds traces of colonial times and communism, whereas in the US, it holds traces of slavery that resulted in a civil war. I try to eliminate control and often press to bring something real to the work without censoring myself, to dig at something important even though it is hard to see or difficult for us to think about. Often the work comes across as grotesque or has a strong punch.

Farah: From there, I also noticed how your exploration of the medium became more daring, multi-dimensional, and versatile, as shown in your seminal exhibition, ‘Inter-Eruption’ at Bentara Budaya in 2005. Wild, no hold- barred use of materials from eggshells, metal, and correct me if I’m mistaken – but I think this was the time you started to do highly elaborate performance works. This medium exploration is also parallel with your subject- matter at that time, which said a lot about societal anxiety, fear andhidden/repressed violence in relation to cultural identity, religion and faith, and politics, with striking, grotesque, theatrical visual language. Can you mention one work during this time that you regard most important, or special?

Entang: I have to discuss two works, Floating Eyes and Fucking Lucky (2004), because they are really connected to each other. Floating Eyes highlights two landscapes (mindsets), that describe the internal and external, as well as the individual and the collective. The work follows the flow of the majority group that watches the individuals within it who are following or resisting the system. The eyes seek protection or seek to protect, to monitor and judge individual actions. This work is a reflection on the Reformation Era in Indonesia. Under the Suharto regime, people were forced to follow along and when change came, the people followed the majority opposition. A change in power still maintained a lot of the systems, because our understanding of power hadn’t changed. You can’t just shrug off a mindset that has been instilled over generations and those changes in Indonesia are still in process. The legacy of colonialism, which the Indonesian people despise, still is present in the way we live and think. I see this in the art world in Indonesia as well, and people don’t want to discuss it.

Fucking Lucky is a personal examination of those conditions. People subconsciously or consciously follow a system that defends the majority, namely the white people. Fucking Lucky presents the idea that no matter what, I am always a lucky person for marrying a White person. People always see with one eye full of prejudice. Fucking Lucky is a symbol of the privilege of skin color and the political orientation of domination. It’s about how certain power is always protected. The wide variety of materials I use in these works and throughout my practice are important because I need them to express the development of my vocabularies and to maintain freedom from the system that is still trying to limit or define what is possible. Choosing various media for me represents freedom of expression.

For a long time, the world has been controlled by systems that divide us. This is true in the art world as well. It has always been divided from the beginning through the hierarchy of societies, including churches and academies, by the designation of palace artists and outsiders, the influence of gatekeepers on the official canon and the insistence of isms. As an art student, I needed to understand styles and periods and so on in order to understand the origin of art. For me, ideally, art is free from the burden of any system, whether religious, political, racial or educational. The most influential systems that exist to this day are the colonial, slavery, and gender systems.

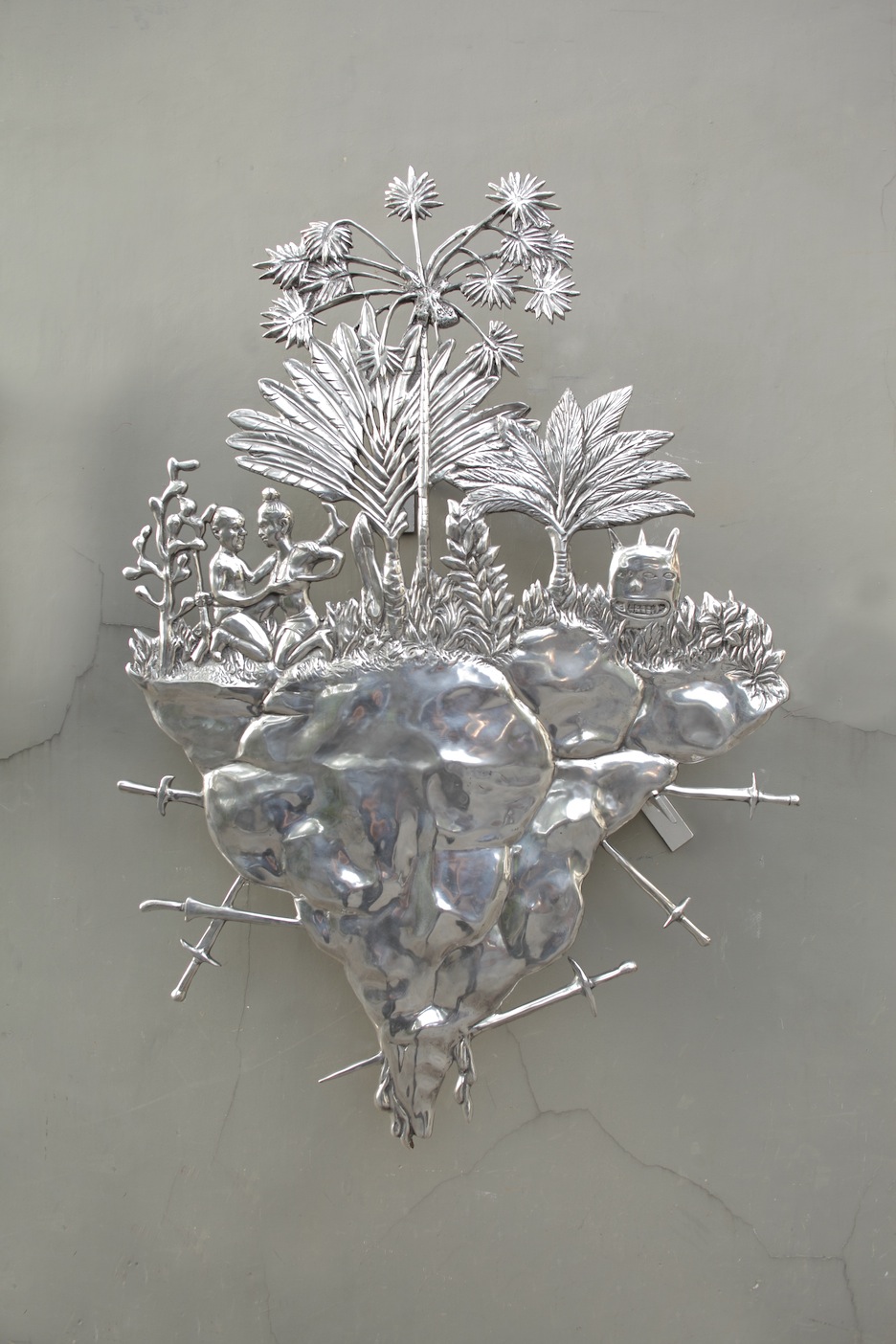

Farah: From around 2010 onwards, you started to develop your famed aluminium works, while the subject- matter – as shown in the paintings such as the Floating Island series, somehow shifted towards something broader on how you see the world,the idea of Paradise Lost but also at the same time more hopeful. I wonder what’s your take about these works now, including your choice of medium, like aluminium – which you’ve been very consistent in using from then on, until recently.

Entang: The origin of my aluminum works began with a painting whose background failed. I wanted to save the human figures in the painting, so I cut them out and mounted them on aluminum and from there they developed into flat statues resembling puppets. My exploration of aluminum continued when I made embossed prints using aluminum cut- outs and then reactivated the negatives by rearranging the cut-outs into independent works mounted on the wall. The beauty of raw materials such as aluminum, stainless steel, and copper is something else. These materials represent modernization, with these materials appearing in our daily lives.

The works Paradise Lost and Floating Island are open-ended questions about how imagery was used in the colonial era and how that use continues to resonate and influence us today. I researched how people describe and document to take and determine ownership of their colony. As I looked at the colonial controlled images of my country, I determined a new way of representing the Indonesian landscape. The orientation is the land rather than blue sky. The land is always here as a witness and the sky is always moving and changing. I began to create an extremely divided painting, delineating two sections of land and sky. The sky is raw canvas to create as sharp a landscape as possible to present a black and white division and establish a sense of shadow or silhouette. I want to reclaim my own landscape in order to separate from the past, which is heavily claimed by western powers. This painting was influenced by my own practice of creating cut-out metal work as flat sculpture. This work reflects my intention to throw something I don’t need out, which in this case is the background or something non-essential to me.

Farah: Can you tell us more on your current project with Guggenheim, Temple of Hope: Tunnel of Light? From our last conversation I also see how you are now working a lot with the subject of nature, like your observation of plants and trees and archiving them. You also spent a lot of time – especially during quarantine, nurturing your garden. Is there any relation to the project, or what’s your most current interest now?

Entang: My Guggenheim Fellowship is to research and develop ideas for a new body of work through travel to areas of the United States with historical significance and to sites where artists have created artworks dealing with landscape, light and shadow. The historical context of the sites illuminates the current state of discourse about migration, tolerance and peace.This research informs my current projects and plans I have going forward. For the research part of the project, I planned to visit areas of the United States with important connections to the American story, particularly places connected with narratives about expansion, conflict, morality, belonging, and equality.I’m interested in the origin stories of the American character and key historical experiences that shaped American relationships with the land.

I have had to adapt to the new situation caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. I wasn’t able to travel to several places in my original research, in particular to see Walter De Maria’s installation The Lightning Field in New Mexico, the painted desert region of northern Arizona where James Turrell’s Roden Crater is located, as well as the mid-western American landscape, including the Grand Canyon. I did travel to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to study the area where the pivotal Civil War battle between the North and South took place and learnt more about how American history was shaped by the landscape. I traveled along the Eastern seaboard from Rhode Island in the north down through Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and finally to Marfa, Texas where Donald Judd created much of his seminal works. During these trips I made photographs, video, and sound recordings as well as sketches and drawings. In addition, I documented conversations and collected books, articles and other publications to inform my research. I will continue with this project when it is again safe to travel.

For the last ten years I have been interested in works about objects and light. This interest is inspired by the use of shadow in performances of wayang kulit, as well as in traditional and modern theater and the Hindu and Buddhist temples in Indonesia. Light and shadow play an important role in traditional Indonesian art forms and temples. Shadow puppetry has the capacity to connect audiences to all kinds of issues in global society. It has been used in Java to create awareness and as a form of propaganda.The temple sites surrounding my studio in Yogyakarta were built with lava stone from nearby Mount Merapi, one of the most active volcanoes in the world. The black and grey-hued stone creates darkness in the temple interior and generates contrasts with the bright sun of the tropical surroundings.

Landscape is critical in the development of human history, impacting the creation of civilizations that mark our existence and our ability to survive. Landscape also has strong associations with home. Every time I visit a temple in Indonesia and look out at the surrounding landscape, I remember James Turrell’s work, especially Roden Crater, and Walter DeMaria’s The Lightning Field. I feel that their works, man-made structures like the ancient temples, underscore our connection to the earth, de-emphasize the now and force a reckoning of our ephemeral place in the trajectory of time. Architecture changes and marks the landscape, creating and building memory and history.

For the Guggenheim, I want to extend my previous installations of temple structures into the landscape, bring the setting and background into focus.Based on my research, I have created small scale models for the project Tunnel of Light. Whereas previous works in my Temple of Hope series removed the structure from the landscape, bringing it inside, this work will take the temple back to the landscape to create a different feeling and perspective. The work engages with the growing intolerance and polarization arising from extreme politics. Misunderstanding, conflict, and tension always exist as part of the human experience. Artwork can compress the past and present, memories and histories, mythology and reality, conflict and peace, hope and despair, weakness and strength. My intention is to create a site where people from different backgrounds can have an experience that reflects hybridity and creates a sense of borderless-ness.

Tunnel of Light is a long-term project about history and storytelling through our physical and psychological connection to the landscape. This project comes from a sustained interest in landscape stemming from my experience as an immigrant, which can be seen in my Floating Garden series that focuses on plants and vegetation. It builds on ideas that connect spirituality and transcendence with national narratives about progress and destiny that I have explored in a series of installations created over the last decade. Botany and gardening have been passions of mine since I was a child. I use imagery of vegetation in my work, especially flowers and edibles, as these are often brought to new lands by immigrants. The use of local ingredients in cuisine, including spices, are often the first step in cultural understanding and fostering friendship and solidarity. My gardens are an integral part of my studio. The care of and experimentation I do with plants in my garden, and my research on agricultural practices directly impacts my artwork and is a part of my creative practice.

Farah: To conclude, after more than 25 years of a very adventurous artistic journey, and also a very transcontinental life between Indonesia and US, what is the next challenge for Entang Wiharso? How do you see your art, the art world, and also the world itself in the future? I also wonder if this pandemic that we are all experiencing now has something to do about it.

Entang: The immediate challenge is how to fund large installations like my project for the Guggenheim Fellowship to realize a full-scale version of the Tunnel of Light installation in a permanent location. One of the big challenges I face is how to maintain my archives so that in the future people have access to the development of my work and my practice as it occurred and within an historical context. Christine and I think about this often. We understand the importance of planning for this now and the need to lay the groundwork, especially because it is a transcontinental undertaking. I think the pandemic will change the art world and how we operate and interact. I think this situation will have a sustained impact on how artists will be functioning in society, maybe rethinking how and what medium will be more functional in this new normal.

Copyright and Image Credits:

© Entang Wiharso and Mizuma Gallery.