“I’m trying to capture silence. Even though it’s an impossible task and silence is what captures me for the most part, I persist.”

– Albert Yonathan Setyawan

Indonesian contemporary artist Albert Yonathan Setyawan is busy preparing for his upcoming survey exhibition, “Capturing Silence” (6 October – 5 November 2023), at the Jogja National Museum in Yogyakarta. The exhibition, curated by the artist himself, will feature more than 90 works spanning 15 years of his artistic output. From his studio in Tokyo, Setyawan sat down with Singapore-based art writer Yvonne Wang to talk about his approach to art making, his discovery of phenomenology, and his admiration for German artist Wolfgang Laib.

___________

Yvonne Wang: You have consistently used ceramics as your main medium. What are you able to convey through the medium that you cannot express using other materials?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: This is an old question that I have been grappling with since my university days. During my graduation show, my teachers asked me, “Why clay?” But I was unable to give them a straightforward answer at the time. It was a mystery to me as to why I was interested in clay. I originally wanted to do printmaking. I hated painting – it’s just so boring. I needed something more tangible. I wanted to work with matters – with plates, inks, and machines. I was fascinated with printmaking at first. But then I came upon ceramics and found it to be even more fascinating. It just clicked. Still, I never fully understood why until I came across phenomenology or philosophy of experience. One of the first books I read on the subject was Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. In it, he emphasises the poetic dimension of objects and spaces. He talks about how through the power of imagination and poetic reverie, objects can take on new meanings and become vessels for creative expression. In this sense they cease to be ordinary objects as they transform from their physical existence into the realm of imagination and symbolism. I was fascinated by this concept and realised that this is what I want to do with clay – to look deeper into things. From there, I discovered two of his books about clay titled Earth and Reveries of Repose and Earth and Reveries of Will. He delves into the various ways in which earth is perceived and experienced, both materially and metaphorically. He discusses the concept of earth offering shelter and how the feelings of stability it evokes help to inspire creativity and introspection. I view clay now from this perspective. I see it as an extension of the human body – a repository of memories. It is a medium through which I can look deeper into things.

Yvonne Wang: You wrote your PhD thesis on Hendrawan Riyanto, the late Indonesian contemporary ceramist who taught at Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) when you were an undergraduate student in the Ceramics Arts department. Riyanto viewed clay as a metaphor of the human body and saw ceramic-making as a symbol of spiritual transformation. Do you agree with him?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I used to agree with him but now I see it differently after I encountered the works of Bachelard. I wish I read it when I was writing my PhD thesis because if I had, I would have written it differently. I am less convinced now that clay is about spirituality. I think Hendrawan understood it in that way. I used to see it from the same lens when I first began my practice. Whenever I had to write about my work, I wrote about it from the perspective of spirituality. I grew up in a Christian family and spent most of my youth in the church. My worldview at the time was very much shaped by the church, the bible, and the gospel. My mother died when I was a first-year student in university. By the time I was about to graduate, I felt mentally and spiritually exhausted. I left the church and just wanted to focus on art – on becoming an artist. Somehow, I came across the Theosophical Society which is an international organisation that encourages open-minded enquiry into world religions and philosophy. From there, I was exposed to Buddhism, meditation, and the mandala. When I think about clay now, I am less convinced about spirituality which is where Hendrawan and I are different. Spirituality implies that you believe in something that is not physical – for example, the idea of the spirit which is opposed to the body. It is underpinned by a dualism between material things and immaterial things. When you talk about spirituality, there is always an emphasis that the spirit is the true self. I try to surpass this dualistic thinking in my work in the same vein as Dutch thinker Baruch Spinoza’s claim that the mind and body are two sides of the same coin. What I’m doing now is based on the physicality of my own body. I cannot do what I do without realising that I am this body. Hendrawan saw clay as a metaphor of the body, but a metaphor by definition implies a kind of detachment. For me, clay is not a metaphor for the body, it is the body. Having said that, I think Hendrawan and I both agree on the potential of clay as a medium through which abstract things can be made concrete and perceptible. Clay is one of oldest materials used by humans. So many creation myths and origin stories across cultures are based on clay. The medium is really an embodiment of human experience.

Yvonne Wang: It is true that clay objects possess the capacity to draw together seemingly incommensurable transcultural and transhistorical narratives. What story or stories do you wish to tell with your ceramic practice?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: This is a very tough question. I don’t really know. This is a very good question.

Yvonne Wang: How about we come back to this one?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Okay.

Yvonne Wang: When I look at the motifs you use in your work. You draw your inspiration from traditional ornaments, symbols, and historical sites across diverse cultural and religious traditions. Would you describe your approach as syncretic?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I would. That’s a very good way to describe my practice.

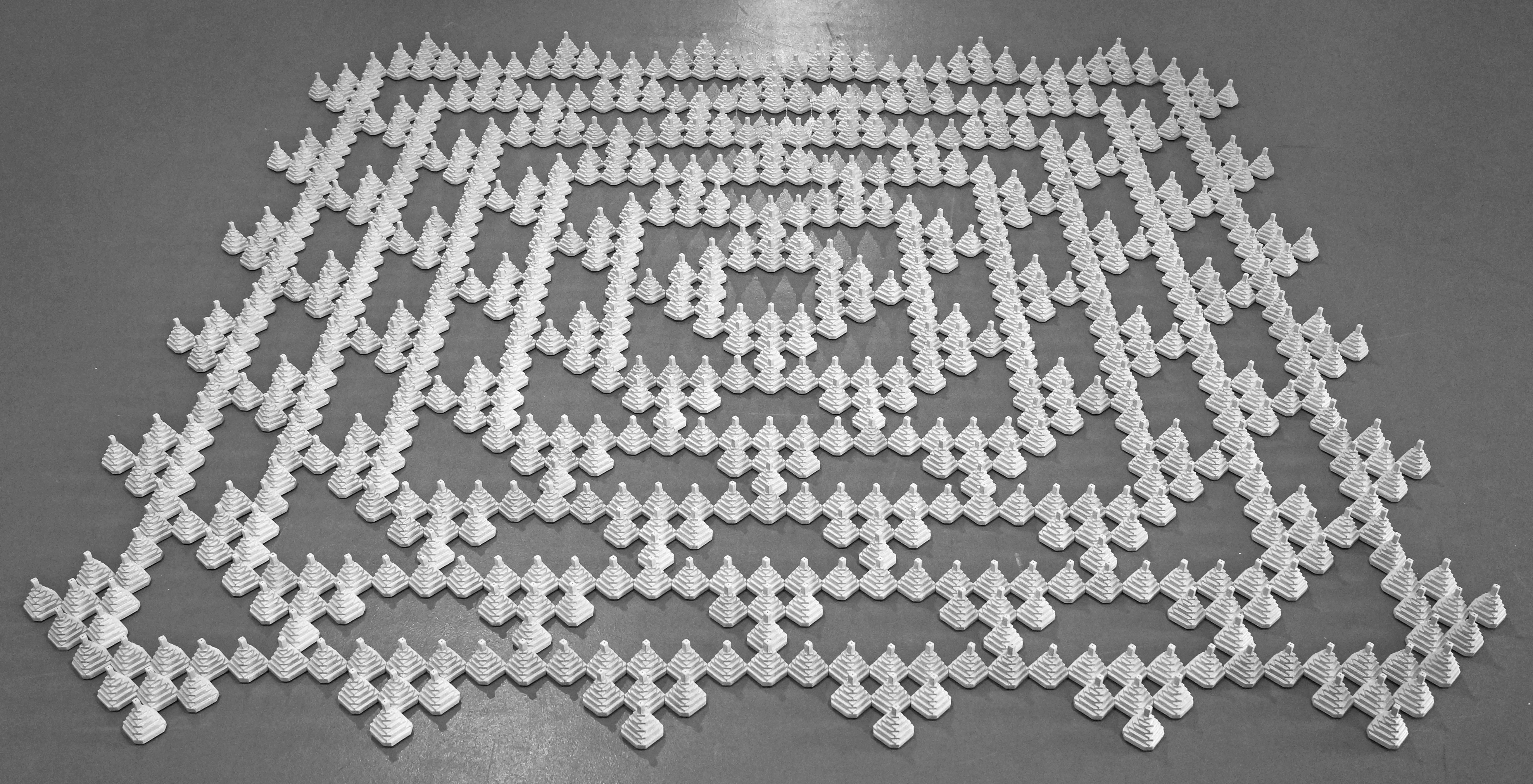

Yvonne Wang: Many of your installations are based on the mandala, a symbolic representation of the cosmos in the Buddhist and Hindu religions. In Jungian psychology, the mandala is seen as a representation of the self – an archetype of wholeness within the human psyche. What draws you to the mandala and what does it represent to you?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: When I was doing my master’s, I was interested in exploring the idea of using my art as meditation. Instead of sitting in the mountains, I sit in my studio for hours making works following a process that I’ve developed. That is my meditation. What you see in the work is a result of that process. It was through my interactions with Buddhism that I became fascinated with mandalas. I made many works based on the mandala, but after a while, I asked myself why am I so interested in this visual form? It occurred to me that what I’m most attracted to is the idea of multiple emanations embodied in the mandala. I’m interested in repetition, sequence, and the idea of multiplicity. From there, I began to look at the mandala with more depth. One thing that I’ve always been interested in is “the body” which I wasn’t aware of at the time. Every mandala requires the physical presence of the body. The creation of a mandala requires the performance of a physical act. I think Buddhism is one of the few religions that doesn’t reject the body. It acknowledges the body. The body isn’t necessarily something that you have to overcome. It is through the body that one achieves enlightenment. This is what I’m looking for.

Yvonne Wang: So, mandala as a representation of the body?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: In a way, yes. I really like this TV series called Cosmos by Carl Sagan, the American astrophysicist. He famously said, “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff.” In this way, we are connected to the cosmos. If the mandala is a representation of the cosmos, then it is also a representation of the body. When asked how many times you would have to cut an apple pie in half to reach the size of a singular atom, Sagan gave a number which I can’t remember off the top of my head. The point is that if you look into an atom, there are protons, neutrons, and electrons that exist within a vastness of space. They say atoms are 99% empty space and if they make up 100% of the universe, then everything is composed of nothing.

Yvonne Wang: We’re often misled into thinking the mandala as a static form or image. Imbued in the mandalas you create is a sense of movement around a central axis. I’m really intrigued by the notion of the mandala as something that is constantly moving, changing, and unfolding. Could you elaborate on this idea?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I agree. I think that’s a beautiful way to put it. I never saw it as a static thing. I was interested in the mandala as an organic thing that changes – like the sand mandala that is created and then destroyed. I like your description of movement. I think this was the reason why I smashed the bells in Cosmic Labyrinth: The Bells (2011-2012). I created the work when I was doing my master’s and I carried it around, using it as a tool to perform and create different mandala structures. At the final stage, I thought of how I am going to end the performance and I thought I’ll just smash it. Because I feel like at the time when I smashed the bells, I freed the mandala from its binding. I think that’s how it is supposed to be – to be organic and impermanent. I never thought about it in the sense of movement but now that you’ve mentioned it, you’ve given me some ideas.

Yvonne Wang: In Tibetan, the term kylkhor (Sanskrit: mandala) is used to describe a magic circle that contains. It is also associated with the term khorlo or wheel which implies a sense of movement like the turning of the wheel of Dharma.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: This is very interesting to me. I think when people look at ceramics, they also think of it as a static thing. This is also part of my struggle with the medium. In ceramics, there’s often this fetishism of technique. When ceramicists get together, they obsess over the type of clay and glaze, and the firing temperature. They focus so much on the technique and output as if they want to preserve the beauty, value, or quality of the objects they make. So, it becomes static. But it’s about movement and change. I think we can translate the idea of the circle into our relationship with objects. I’ve been making ceramics for 15 years thinking that I am the subject that makes the object but then it dawned on me that it’s actually the opposite. It’s not me who makes the object, but the object makes me. Through the act of making, I become the project. It’s this idea that when you cast something it eventually comes back at you.

Yvonne Wang: Like a boomerang.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: That’s right. You think you’re the subject but then the object sort of looks back at you and you realise that you are the one that is in the making. I think it’s beautiful.

Yvonne Wang: Is the object looking back at you or is it holding up a mirror?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I think the object is more like a mirror. It reflects back at you. I think that’s how consciousness works. We project onto things to get a sense of who we are. This is something that I often thought about when I was a child. How is it that I’m only able to gaze outward but never inward? I can see all these beautiful things outside of my body with my eyes, but I can’t see what’s inside. It creates a blind spot. I read an article about how our brain mutes the sound our bodies make so that we can tune out and focus on the outside world. I think that’s really interesting. That’s what we’re dealing with when it comes to objects. Overtime, humans learn that they are hard-wired to create, to make things. But then these things serve as a mirror to reflect back on their makers’ own conditions. This idea that we extend our physicality to things and in so doing, it produces a sort of mirror that reflects back at us so that we can understand what’s inside, what we cannot see. It’s beautiful. I see art in that way.

Yvonne Wang: You put a lot of emphasis on physicality. I think it’s interesting how clay engages virtually all sensory modalities of the maker yet from the point of view of the audience, so much of the experience is removed.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: This is what I’m struggling with. It’s so true. So much is focused on the output and not the process. All these beautiful objects weren’t so beautiful when they were in the studio. All that mud, glaze, and dust. They are born of mess. These are important aspects of ceramics that are cut off when they’re presented to the public. It’s a detached experience. I’m trying to figure out how to bring back these sensory experiences to draw people in.

Yvonne Wang: Speaking of mess, I’d like to talk about the idea of orderly chaos which is embodied in the definition of the mandala that you explore in works like Cosmic Labyrinth: The Bells (2012), Mandala Study #3 (2015), and Mandala Study #4 (2015). Could you talk about how this applies to your practice?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I mentioned Spinoza earlier. He has this theory of modes which says that modes are particular expressions of the one divine substance which he refers to as God or Nature. According to Spinoza, everything has two modes – a material mode and an immaterial mode. The material is not opposed to the immaterial. They are different aspects of the same thing. His philosophy is often considered pantheistic, as he viewed God and Nature as synonymous. I agree with Spinoza, and we can approach the idea of orderly chaos from his perspective. Order and chaos are not separate things. They are two modes of the same thing. You can’t split them apart. Cosmic Labyrinth: The Bells is an exploration of this idea of orderly chaos.

Yvonne Wang: Your practice is incredibly labor-intensive and time-consuming since you handcraft everything on your own. I see this temporal dimension to your ceramic practice that is akin to durational performance. Could you talk about the presence of performance or performativity in your practice?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Performativity is inherent in ceramics. There’s always a performative aspect to ceramics no matter how you talk about it. For some artists, the performance aspect may not be their key focus. When it comes to the ceramics-making process, I’m convinced that I must make things myself rather than outsourcing it to artisans. Because the audience is largely detached from processes like we talked about earlier, it became even more important to me to engage myself in every aspect of execution from mold-making to casting and firing. I disagree with conceptual art’s claim that ideas alone can be works of art. I don’t think the idea is the most important aspect of an artwork. I think both the idea and the object are important because ultimately what you’re presenting to the audience is the object. If only the idea is important then why bother presenting the object at all? Why not just write a paper about it? Ultimately, I’m against the separation of the idea and the object. I’m opposed to this dualism. This is why I do everything myself. It’s really hard sometimes to keep up with the demand and recognising the limits of my own capacity to make things. In Indonesia, it’s so easy to find artisans to do the work for you and it’s so cheap. There’re a lot of artists who send their sketches to foundries and have the works made in one or two months. The artisans get paid very little and the artists get paid a lot for what they don’t make themselves. I don’t want to do that.

Yvonne Wang: Your employment of restricted palettes, geometric elements, serial arrangements, and common material in the form of terracotta shows an affinity towards the visual strategies of Minimalism which came to prominence in America in the 1960s but has its roots in Eastern philosophies such as Taoism and Zen Buddhism. The latter had a huge influence on the art and culture of Japan. Could you talk about how your experience of living in Japan has affected your work?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I’ve been living and working in Japan for 10 years. I think living in Japan has influenced my work ethics and approach to materials. Many artists I like are part of the Minimalist art movement such as Agnes Martin and Mark Rothko. Separately, I also really like Wolfgang Laib’s work. He’s one of my favourite artists when it comes to matters. You can see his work from a Minimalist perspective, but Minimalism has this aspect of reducing the involvement of the artist. But in the case of Laib, it’s quite the opposite. He was very involved in his pollen work. He went out every day to gather jars of pollen in the countryside and used them to create installations that resemble Minimalist-style paintings. It’s Minimalism, but it’s not that kind of Minimalism.

Yvonne Wang: It’s Minimalism with maximum effort.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Yes, exactly. I realised that’s what I’m drawn to – the physical engagement or art labour. I’ve always had this desire to rebel against norms. The reason why I use terracotta is because in ceramics, there’s this excessive fascination over the sensual aspect of glaze. Everyone worships porcelain and shiny surfaces which I just hate so much. I want to use the cheapest and simplest material where there’s no mystery to it when it comes to technique. When people ask me to conduct a workshop I usually say no because I have no secrets to show people. My practice is really simple, basic, and minimal.

Yvonne Wang: You’ve always been fascinated by the idea of repeatedly performing certain actions to a point where the action’s significance goes beyond its original meaning. I’m interested in the transformative element of your work, particularly how you blur boundaries between the sacred and the profane. Could you talk about this duality in your work?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: The idea of repetition came to me very early on when I was doing my bachelor’s degree. I thought if I do one thing over and over again, eventually I’ll end up in a different place. This is the nature of things. Everything moves and it cannot stay the same. I was very intrigued by this. I was also rebelling against the idea of creativity – of the idea of the artist as a creative genius. There is so much emphasis on newness. People often ask me whether I get bored doing the same thing or working with the same material because they think creativity means you have to constantly engage with different things. They think the value of the artist comes from the fact that the artist is able to use different mediums. One minute the artist is doing video work and next, he’s off to performance work and painting. I hate this idea. Why do I have to explore so many different things? Why can’t I just stick to one thing? I just want to do the same thing over and over until eventually I end up somewhere else. I want to prove that you cannot understand creativity in that way. In fact, I don’t like to use the term creativity now precisely because of this obsession with newness. I don’t think we ever create anything new. I don’t think what I do is an act of creation. I prefer to use the word “produce”. I’m not creating things; I’m just composing things. It gives me this understanding that things are already there and I’m merely uncovering their potential by combining them in different ways that are unique and authentic to me. Does that make sense?

By doing things over and over again, I’m trying to demystify the idea of the artist as the genius who owns the idea, and the object is just a product of the technicians who translate the idea of the artist. I want to defy this separation by engaging in the process myself and by being present. The act of making is an experience. The object is the manifestation of the experience in its concrete form. It embodies traces of the experience.

Yvonne Wang: In your ceramic installation, each identical part is an integral dimension of the expressive whole. How would you describe the dynamic relationship between the individual parts and their relationship with the cohesive whole? What about the correlation between different works?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: These are interesting questions. Even though they are separate works, I always see them as one whole ensemble like an orchestra with many different instruments. They are different works when it comes down to individual pieces. But when it comes to process, they are more or less the same. Sometimes I think of the pattern first and then the object but sometimes it could be the other way around where I’ll think of certain shapes and then the arrangement. I rarely use sketches. I normally just use clay. When it comes to presenting my works, I always see them as part of a bigger picture. That’s why I like to do solo shows because I get full control of how the works are presented in a coherent way like my upcoming show at Jogja National Museum. I’m terrible at titles. The title always comes after my work is finished. If I look deep down, what’s important to me is the repetition. That’s what I enjoy. The individual shapes are less important than the process of making them. For example, I’m working on a big installation for next year which has over a thousand pieces. Oftentimes, people ask me about the symbolism of the individual shapes, but I don’t really get excited by it. I’m more interested in the repetition. When it comes to the reality of making, when I’m holding an object in my hand and carving it, I seldom think about its symbolic significance. Instead, I’m focused on the lines. It’s about repetition, reproduction, and iterations of the shapes. It’s about continuous labour.

Yvonne Wang: The individual parts that make up a particular work appear to be identical, yet each piece is a singularity with its uniqueness. French theorist Gilles Deleuze explores the concepts of repetition and difference in his work. He suggests that repetition is not mere duplication but involves variations and differences. Could you talk about the idea of difference within sameness in the context of your work?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: That’s exactly what I’m interested in. It comes from trying to confront the tensions between the mechanical and the organic. I’m interested in the idea of using my body as a machine to produce the same thing over and over again. I try as hard as I can to achieve the same results but obviously, I fail because I can’t make them the same each time. There’s always something different. It’s like when you draw a straight line. You do that 100 times and you have 100 straight lines but they’re not the same. I got this idea from Agnes Martin’s work. When you look at her work, it seems so simple, so plain but then it’s so enigmatic and complex because you realise that you can try as hard as you can to draw the same straight line, but it’s not possible. They are the same, but they are also different. Sameness and difference are not separated. In Spinoza’s view, while things may appear distinct and separate on the surface, they are all expressions of the same underlying reality. That’s what’s important in my work. I hope people realise it.

Yvonne Wang: I’m struck by the modest scale of each ceramic component. There is a certain intimacy to objects that can fit in one’s hand. Yet together they point to grander revelations. Can you discuss the relationship between the personal and the profound in your work?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: There’s something really interesting working with small objects. They create a sense of intimacy and closeness. But if I multiply them and install them in a certain way – they create this strangeness. A large installation can overwhelm the viewer with its scale. It has this ability to draw you in. It makes you want to look closer and when you do, you realise each object is different. That’s the beauty of it. And it is why I insist on doing everything myself. If I give it to other people, this aspect of my work will be completely lost. People have to sense that by looking at these objects, the fact that they are different is because every single one of them came through my hands. I touched them, I held them many times from the moment I took them out of the mold, I carved them, I put them in the kiln, I took them out of the kiln, I wrapped them, I put them in a box and sent them to the gallery. They went through the touch of my hands.

Yvonne Wang: We talked about metaphysics earlier. Would you say your installation is defined by the ceramic objects or the space or void around and between them?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Both, I would say. This is something that came to me not long ago. I realised that the shadows they produce are very interesting. They create a different layer between the objects and the walls. In my essay, I wrote that the shadows help free the object from its objecthood. Objecthood refers to the quality or state of being an object. An object has certain properties and criteria that makes us see the object as an object under certain conditions that also establish us as the viewer. I realised that by focusing our attention on the shadows and space around the object, we become less aware of the object. The object becomes more elusive. And as a result, we longer see ourselves as the subject viewing an object, but we become part of the space, the cohesive experience between the object and ourselves.

Yvonne Wang: Light obviously plays an important role in your work.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Yes, without lights the shadows won’t appear. I’m very sensitive with lights these days. I try to use one light for one work so that shadows stay sharp. It has a huge impact on the way people experience the work. It makes me aware that it’s not just about the object, but how I present it to the audience.

Yvonne Wang: Much has been written about the meditative quality of your work both in terms of artistic process and visual experience. Riyanto saw no difference between art and meditation because for him, meditation is the practice of the mind and art requires the same practice. What role does meditation play in your work?

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: Meditation plays a huge role in my practice. I didn’t do a lot of shows when I was a student. I was experimenting and reading a lot. I didn’t really have a strong sense of purpose until I discovered meditation. I wouldn’t have arrived at where I am today in terms of my ideas without meditation. Being introduced to meditation practice allowed me to develop my artistic concept. I don’t meditate every day in the traditional sense. For me, art is meditation.

Yvonne Wang: The title of your upcoming solo exhibition at the Jogja National Museum is “Capturing Silence”. Could you tell me more about the inspiration behind the title? To me, silence is not something that we can capture, rather it captures us.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I agree with you. I named the show “Capturing Silence” because I wanted to expose the impossibility of it. The idea came to me when I was reading a book called Deleuze and Art. I was interested in understanding what Deleuze thought about art. For him, art is not about reproducing or inventing forms, but of capturing and manipulating forces. This is very much in line with my own understanding that art is not about creating new things, but of composing things that already exist. It’s about capturing the intersection of things, ideas, and moments. I’m really intrigued by the idea of capturing things. I try to use that metaphorically to explain what I do with slip-casting which is the main technique I’ve been using so far. Slip-casting is almost like capturing things because you trap the shape in the mold so that you can reproduce it. Then when it comes to silence, it’s a title that I’ve used for my very first work that I made shortly after I graduated from ITB in 2007. The upcoming exhibition is a survey show so it’s all about revisiting and looking back. So, I thought it would be nice to use a title that I’ve used at the beginning of my career.

I came across a book called The World of Silence by Max Picard. It’s a meditation on the idea of silence. Picard’s definition of silence can be very obscure, but it can also be very concrete. He says silence is not merely the absence of sound but a fundamental human experience. For Picard, silence manifests in so many different things. It can be found in different periods of transition, for example the changing of the seasons and the transition between dawn and sunrise or between sunset and dusk. What he’s trying to say is that silence is a place in our psyche where creativity emerges. It’s similar to Gaston Bachelard’s notion of reverie.

Yvonne Wang: This also reminds me of the Buddhist idea of stillness which is closely related to the practice of meditation. When you do breathing meditation, stillness can be found in the moment between breaths. There’s a certain suspension to the stillness. It is not emptiness but a vastness in which everything is possible.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan: I think that’s exactly what Picard is talking about. It’s really hard to describe it. When you mentioned meditation and the stillness between breaths, it reminds me of the idea of no-self where all kinds of potential exist. This is where the definition of silence comes from. It’s a poetic way to describe what I’ve been trying to do in the past 15 years. I’m trying to capture silence. Even though it’s an impossible task and silence is what captures me for the most part, I persist. We talked about how objects serve as a mirror that reflects back at us. I think it’s a beautiful way to frame my practice. It gives me a deeper understanding of what I want to do and how I want to proceed as an artist and as a ceramist.

Yvonne Wang: Earlier on, I asked what story or stories you wish to tell with your ceramic practice. I think you’ve just answered it. That’s the story.

—

This dialogue is taken as an excerpt from an online conversation between Yvonne Wang and Albert Yonathan Setyawan on Tuesday, 29 August 2023. “Capturing Silence”, a solo exhibition by Albert Yonathan Setyawan at Jogja National Museum (JNM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, will run from 6 October to 5 November 2023. Information about the exhibition can be found on www.mizuma.sg and on our Instagram page @capturing.silence.

Copyright and Image Credits: © Albert Yonathan Setyawan, courtesy of Mizuma Gallery.

About the Writer

Yvonne Wang is an art writer and publicist with over 15 years of experience working across the Asia Pacific. In addition to researching and writing about contemporary art for publications such as The Art Newspaper, ArtAsiaPacific, and Asia Art Archive’s IDEAS Journal, she also collaborates with art platforms to create bespoke content to drive engagement. Yvonne holds an MA in Asian Art Histories from Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research interests lie in understanding how culturally and historically embedded mediums become contemporary and global. She also has an MSc in Politics and Communication from the London School of Economics.

Yvonne Wang is an art writer and publicist with over 15 years of experience working across the Asia Pacific. In addition to researching and writing about contemporary art for publications such as The Art Newspaper, ArtAsiaPacific, and Asia Art Archive’s IDEAS Journal, she also collaborates with art platforms to create bespoke content to drive engagement. Yvonne holds an MA in Asian Art Histories from Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research interests lie in understanding how culturally and historically embedded mediums become contemporary and global. She also has an MSc in Politics and Communication from the London School of Economics.

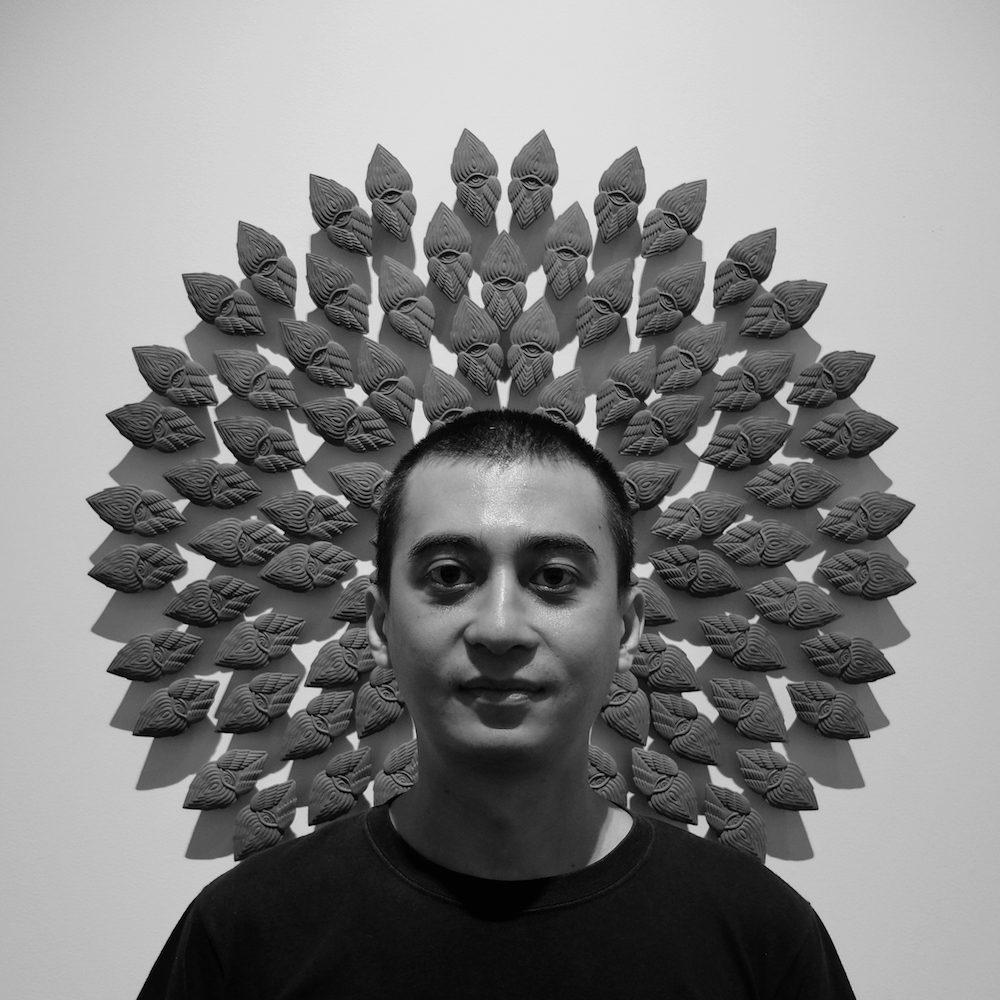

About the Artist

Albert Yonathan Setyawan (b. 1983, Bandung, Indonesia) graduated from Bandung Institute of Technology with an MFA in Ceramics in 2012. Following that, he moved to Kyoto, Japan, to continue his research and training in contemporary ceramic art at Kyoto Seika University, from which he received his doctoral degree in 2020. He has participated in several major exhibitions such as the 55th Venice Biennale (2013); SUNSHOWER: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (2017); and Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia (2019). Setyawan has undertaken artist residencies at Canberra’s Strathnairn Arts Association, Australia (2016); and The Japan Foundation at Shigaraki Ceramics Cultural Park, Shiga, Japan (2009). His works are in the collections of Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia; Tumurun Private Museum, Solo, Indonesia; POLA Museum Annex, Tokyo, Japan; OHD Museum, Magelang, Indonesia; Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu, Japan; Singapore Art Museum, Singapore; and Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park, Shiga, Japan. Setyawan has built his artistic practice mainly in the field of contemporary ceramic art, however, at the same time he also translates his conceptual ideas into various mediums such as drawing, multi-media installation, performance, and video documentation. Setyawan currently lives and works in Tokyo, Japan.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan (b. 1983, Bandung, Indonesia) graduated from Bandung Institute of Technology with an MFA in Ceramics in 2012. Following that, he moved to Kyoto, Japan, to continue his research and training in contemporary ceramic art at Kyoto Seika University, from which he received his doctoral degree in 2020. He has participated in several major exhibitions such as the 55th Venice Biennale (2013); SUNSHOWER: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (2017); and Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia (2019). Setyawan has undertaken artist residencies at Canberra’s Strathnairn Arts Association, Australia (2016); and The Japan Foundation at Shigaraki Ceramics Cultural Park, Shiga, Japan (2009). His works are in the collections of Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia; Tumurun Private Museum, Solo, Indonesia; POLA Museum Annex, Tokyo, Japan; OHD Museum, Magelang, Indonesia; Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu, Japan; Singapore Art Museum, Singapore; and Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park, Shiga, Japan. Setyawan has built his artistic practice mainly in the field of contemporary ceramic art, however, at the same time he also translates his conceptual ideas into various mediums such as drawing, multi-media installation, performance, and video documentation. Setyawan currently lives and works in Tokyo, Japan.