This month on Mizuma Conversations, we put spotlight on artists Agan Harahap, Gilang Fradika, Okamoto Ellie, Yamamoto Aiko, and curator Hermanto Soerjanto and the group exhibition Hopes & Dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma currently on view at Mizuma Gallery, Singapore.

Moderated by Fredy Chandra, this conversation was held live at the gallery during an Artists Talk session on 25 January 2019. In this session, Agan Harahap, Gilang Fradika, Okamoto Ellie, Yamamoto Aiko, and curator Hermanto Soerjanto shared with us their stories and experiences of Rumah Kijang Mizuma.

Read the full interview here.

___________

From left to right: Hermanto Soerjanto (curator), Fredy Chandra (moderator), Yamamoto Aiko (artist), Okamoto Ellie (artist), Gilang Fradika (artist), and Agan Harahap (artist).

Fredy Chandra: Hello everyone, thank you for coming today to the Artists Talk session of Hopes & Dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma, our current exhibition in Mizuma Gallery. To start this off, allow me to introduce the speakers: first, we have Hermanto Soerjanto, the curator of the exhibition and also one of the founders of Rumah Kijang Mizuma; followed by Yamamoto Aiko, an artist from Japan who is currently studying in China Academy of Art, Huangzhou. Next to her is Okamoto Ellie, our current artist-in-residence who has had graduated with a PhD and MFA from Tokyo University of Arts; Gilang Fradika, a young artist who graduated with a major in Graphic Arts from Yogyakarta State University’s Department of Fine Arts, and continues to live in Yogyakarta [Jogja]; and lastly we have Agan Harahap, an Indonesian photography artist who is also based in Jogja.

Before we discuss more about this exhibition, I would like to first introduce the artist residency space of Rumah Kijang Mizuma. So my first question is to Hermanto, as the curator and co-founder of Rumah Kijang, how did Rumah Kijang come about?

Hermanto Soerjanto: In the beginning, I never had any intentions to open an artist residency space. As an art collector myself, I ran out of space to store my artworks so I wanted to rent a house in Jogja to store my collection – well, the rent in Jogja is so much cheaper than in Jakarta [where Hermanto resides]. So I asked my friends in Jogja, if they could please help me to find a house that I could rent. Soon enough, Angki Purbandono, a friend of mine and also one of exhibiting artists in this exhibition, showed me a photograph of a house that he came across. Angki and his wife were going out for dinner one day, but they made a wrong turn and he chanced upon the house which he thought was really nice. The next morning, he took some photos of the house and sent them to me. I told him that the house looks nice, kind of like an old house, 50’s style, and very big, but the condition of the house was not very good. He told me to come by whenever I would be in Jogja. After discussing with my wife, I spoke to Mizuma-san about this and he mentioned that it was a good house. But I told Angki that it was too big and he said, “Well, maybe some of the space could be for the artists, Mizuma-san’s artists, to work in.” “Woah…good idea”, I said and I called Mizuma san and asked, “Do you want to share the space with us? Your artists from Japan can stay and work in this space.” “Hey, that is a good idea.” he said. And there it is, Rumah Kijang. The name of Rumah Kijang actually came from Agan Harahap, because kijang means ‘deer’ in the Indonesian language. Let us hear Agan speak more about it.

Agan Harahap: In Indonesia, there is a Toyota car called Kijang, and there’s another car by Daihatsu called Zebra. I was curious about why should they be named after animals, so I looked it up. I found out that in the name Toyota Kijang, the word Kijang actually means ‘a collaboration between Japan and Indonesia’, as it is an abbreviation for ‘Kerja sama Indonesia Jepang’. I also found out that many Japanese cars were named after animals. Well, the name kijang sounds nice. And one night, while I was talking to Angki about the name for the space, I thought about Kerja sama Indonesia Jepang, a collaboration between Japan and Indonesia – house of Kijang. We both agreed on that, and rumah means house in Indonesian, so the name Rumah Kijang was created.

Hermanto Soerjanto: So looking at the history of Rumah Kijang, everything seems to happen spontaneously. The artist residency program in Kijang is very informal, do not imagine this space as an academic place, as it is not at all like that. I always believe that it is important for an artist to be able to produce artworks that is not necessarily based on theories or academic-driven. An artist needs to have an interesting life, and from that interesting life can they develop an interesting point of view towards life. I think that is what differentiates good artists from great artists. So our intention was for Rumah Kijang to act as a space where an artist can stay, and if they want to, they can create paintings. If they do not want to make paintings, they can just hang out with the guys, because in Rumah Kijang there are always people – many people. We have Angki’s office, his studio, and also the office of PAPs. PAPs or Prison Art Programs is a collective where we try to collaborate with people who are in prison to make art. Within PAPs, there are a lot of members who always visit Rumah Kijang. Many of Angki’s friends are always around too. Memet [also known as DJ Metzdub] is one of them, and he will be performing tonight in Block 9 at the Art After Dark event. Agan is also in Rumah Kijang almost on a daily basis. So Rumah Kijang is like a house with so many people of different interests and backgrounds. For foreign artists like Yamamoto Aiko and Okamoto Ellie, to be in that sort of environment gives them insight into a different culture, a different perspective of life, and I think that is what makes Rumah Kijang, Rumah Kijang. Hence, let’s not imagine Rumah Kijang as a very academic residency space or having a very formal setting—it is far from that.

Fredy Chandra:: Is Rumah Kijang a for-profit or non-profit space?

From left to right: Hermanto Soerjanto (curator), Fredy Chandra (moderator), Yamamoto Aiko (artist), and Okamoto Ellie (artist).

Hermanto Soerjanto: Well, it depends on how you see profit, if it is profit in terms of money, I guess it is a non-profit space. We practically donate to the space. We see profit in a different way. First of all, we profit from the promotion of Indonesian art through Japanese artists. I hope and I believe that the foreign artists who work and stay at Rumah Kijang will talk to their friends, fellow artists, curators, or collectors about it, and that to me is profit. Also, I work in the advertising industry—I am working in the art of bullshit, basically (laughs), for more than twenty years now. So through Rumah Kijang, I feel that maybe I have done something gratifying, because my work is not. Mastering the art of separating you from your money—that is my work. But with Rumah Kijang, I feel that I am doing something that is important, and that to me, is also a profit.

Fredy Chandra: From our history, over 25 artists have been there since 2014, undertaking different residency durations in Rumah Kijang. From your point of view, did the artists benefit from the residency programme? Has it resulted in any turning points in their lives or artistic careers?

Curator Hermanto Soerjanto in front of Yamamoto Ryuki’s artwork, Portrait Dairy, 2015-2017, acrylic on canvas, 14.8 x 10 cm, total 289 pieces.

Hermanto Soerjanto: I would not speak about their career, because that is relative. But here is something that I noticed about a Japanese artist Yamamoto Ryuki. I saw his portfolio when he first came to Rumah Kijang; his paintings were so great and stunning with many little intricate details. They were 3 x 4 meters big, and they were amazing. I noticed that there were hundreds of figures in those paintings, and every single one of their faces were of his own face. I looked at another painting—his own face again, then another painting, his face again. So I asked him, “Why do you always paint yourself?” And he said, “Oh, I have previously painted another person.” He showed me this one painting of him and his mother, and that was it. Every other faces that appeared in his works were still of his own.

While he stayed and worked in Rumah Kijang, he initially started painting his own face, but the longer he stayed in Rumah Kijang, I soon realised that he began painting the faces of other people. Here [gestures to a panel in Portrait Diary] is the first portrait that he painted of someone else: Daunbumi Purbandono, who is the son of Angki Purbandono. Subsequently, he painted Angki; Dian, wife of Angki; Kriyip, caretaker of Rumah Kijang; Fatoni Makturodi, fellow artist in residence; and everyone else. He told me that he lives alone in Japan and from what I see, he seems to be quite an awkward person. But in Rumah Kijang, he was surrounded by so many people, hanging out every night and he eventually became more open to other people. I hope he will continue to paint other people’s faces.

Another artist I would like to mention is Yamamoto Aiko, who studied textile. I remembered when she made a drawing on a small piece of paper which she got from Kriyip. She began drawing, and when it felt too small, she would add another piece of paper using duct tape and continued on to draw. As she drew, more and more extensions were made to the paper, resulting in a 3 x 2.5 m drawing.

Fredy Chandra: Let’s now speak with the artists present: Okamoto Ellie, Gilang Fradika and Yamamoto Aiko. While Okamoto-san is still undertaking her residency, both Gilang and Aiko-san have already completed their residency term. Can you share your experiences in Rumah Kijang and the impacts you felt it had on your artistic careers? Were there any ideas that had influenced you? Let’s start with Aiko-san.

Yamamoto Aiko: I was an artist-in-residence at Rumah Kijang Mizuma in 2015 for 5 months, and at the same time, Yamamoto Ryuki and Fatoni Makturodi were there as well. Back then, I was still a university student studying at the Tokyo University of the Arts. I took a year off university to go to Jogja and that was my very first time abroad. At that point, I could not speak English well, but Rumah Kijang, as Hermanto mentioned, is not an academic space. The dynamics of the space was very surprising to me, because back in my studio in Japan, I would normally work alone and be very focused on my artwork. But in Rumah Kijang, there are no walls; it is an open space studio, and when I am drawing, there would be other artists beside me working as well. There were always people around me, either drawing, drinking, or having a conversation. It was all so surprising for me. As Hermanto san said before, an Indonesian friend gave me a pencil and some papers and I started drawing using those materials given. While I was in Japan studying textile, I always used cloth and dying techniques. My time spent in Rumah Kijang changed my style and opened my mind to new materials and techniques.

Fredy Chandra: How about with Okamoto-san?

Okamoto Ellie: For me, as a Japanese, I feel pretty much westernized, and this is my first time staying in another Asian country for a long period of time. I have already been there for more than 6 months, but every single time when I communicate with other artists in Jogja and the local people, I feel like I am learning something new about this society that is entirely different from America, where I had previously spent 10 months during high school. I feel that the people in Indonesia are open-minded and that we can communicate and share knowledge together. Some of them were even willing to offer assistance to me during their free time, and I feel like I am learning these attitudes day by day.

Fredy Chandra: How about Gilang? Even though you live in Jogja, you took the time out to undertake a residency in Rumah Kijang for 4 months.

Gilang Fradika: I did my residency at Rumah Kijang from September till December 2018. The first impression I had of Rumah Kijang was that there were always people in the house. I thought that the work space was conducive. When people visit Rumah Kijang, they will often leave their stories behind, so being in a place with so many people really helps with your imagination. This was the first time that I did a residency and worked in another studio. I was able to learn about the other cultures, for example, from the Japanese artists and other artists from different countries. The Japanese artists are very disciplined in their work, while in Jogja, we on the other hand are so relaxed when it comes to making works.

Fredy Chandra: Next, I would like to ask Agan Harahap, who is not an official residency artist, but is always around in the house. Were there any experiences that you would like to share?

Hermanto Soerjanto: Agan is not an artist-in-resident, he is the resident (audience laughs).

Agan Harahap: When Fredy and Mr. Hermanto asked me, “Hey Agan, you have to join this exhibition on Rumah Kijang”, I said, “Are you serious?”. I think it is difficult for me because I feel like I am already a part of Rumah Kijang and I am not a residency artist there, so what can I do? But after thinking about it, my experience with Rumah Kijang is quite unique. Every time my wife asks about my whereabouts and finds out that I am in Rumah Kijang, she will be fine with that. It is like a safe house for me. I gained so many experiences there, which lead me to create my artwork in this exhibition. I have a specific story about two Japanese artists—cosplay artists—who were having their residency in Rumah Kijang. We were talking about cosplay ideas when an idea suddenly came to me. The Southern Beach of Jogja is a very mystical place. In Indonesian mythology, we believe in the Southern Beach lives a Queen called Kanjeng Nyi Roro Kidul. I suggested to them that they could cosplay as this mystical queen. A few days later, Kriyip came to me and said that I should not have made that suggestion, as people are forbidden from wearing the colour green at the Southern Beach. It’s a taboo. Green is the colour of the queen’s attire—anyone else who wears it may get cursed or harmed. From that experience, I realised that my work needs to communicate what identity is like nowadays. If I am an Indonesian, why must I wear batik to look like an Indonesian? It shouldn’t be that way. So, I decided to create works that juxtapose the different cultures. It started with the experience I had with the Japanese artists dressing up as Nyi Roro Kidul, but I changed the cultural and historical context and arrived at those artworks [Meisjes Uit Indonesië].

Fredy Chandra: I would like to direct my next question to Hermanto, a question we are frequently asked about – is the residency at Rumah Kijang open to anyone who wants to apply?

Hermanto Soerjanto: Yes, it is for everyone. The original idea for Rumah Kijang was for it to act as an open space for artists from around the world. Interested artists are welcome to submit their portfolios to us and we will then review their applications.

Fredy Chandra: How is the selection process like? Is it only limited to artists from certain countries?

Hermanto Soerjanto: No, it is open to all artists. One of the experiences you can get from the residency, especially if you are coming from Japan, is that you get a cultural shock. From the language barrier, transportation, to the time difference. For example, in Japan it is decided that we leave a place at 10:21, we will leave at 10:21 sharp. However in Jogja, people can decide to leave the place 20 minutes later, or even 2 hours later. There are so many cultural differences that you will get to experience in Jogja. I think that this difference in cultures is what makes the experience more interesting. By adapting yourself to the environment, it will temporarily or even permanently change your perspective on life. I think it is this experience that will change the way you look at things.

Fredy Chandra: I would now like to ask the curator and the artists more about this show – Hopes and Dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma. What was the idea behind this exhibition?

Hermanto Soerjanto: Hopes and Dialogues. When we; Mizuma-san, Angki and I, decided to open the house to artists from around the world, I personally did not have any expectations. We thought it would be a really good idea and we went ahead with it. What happened after that really amazed me. In Rumah Kijang, there are members of PAPs, and as I have mentioned, PAPs is an collective who works with prisoners to make art. I spoke with Fatoni [one of the member of PAPs], and asked him about how he felt being in the prison. He went to prison for 5 years, and he was incarcerated with Angki during this time after they were caught for smoking marijuana. Fatoni initially felt very frustrated and homesick, he longed so much to see his family and friends. However, during the second year of his sentence, he felt at home in the prison. He did not have to think about what to wear in the mornings. It was a very simple but cozy life. During the fourth year in prison, he suddenly felt very anxious and confused as to what he would do when he gets back out into society. Will they accept him for what he did before? There were a lot of questions running through his head. When he was finally released, he was even more confused, unsure of where to go and what to do. He could not go back to his parents’ house and so he chose to stay at Rumah Kijang. In Rumah Kijang, he painted every single day. He said that to him, Rumah Kijang is a place where he was able to rebuild hope and adjust his life back into the society. This is what I mean when we talk about about hopes in Hopes & Dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma.

Another memorable event that took place in Rumah Kijang was the birth of Daunbumi Purbandono, the first child of Angki and Dian, in 2015. This took place after Angki was released from prison, married Dian, and moved his studio into Rumah Kijang. Dian gave birth to Daun in Rumah Kijang through a water birth process. This, to me, was another representation of hope. As Aiko san had mentioned before, the place is always filled with people. While you are painting, there will be other artists beside you either making artworks or working. Sometimes, these artists are creating a painting of other artist’s painting. It is this sort of dialogue that is so important as it opens up minds and introduces new perspectives. So that is the hopes and dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma.

Fredy Chandra: As previously mentioned, there has been a number of artists who did residency there, around 25 since 2014. However, in this show, there are only 14 artists out of the 25. How did you, as the curator, select the artists for this show?

Hermanto Soerjanto: Well first of all, there were artists who were unable to participate in this show. Secondly, there was a space limitation. I chose the artists whom I have personal connections with. Otherwise, it will be quite difficult for me to curate. I have to understand their works and their progresses. Many artists who have been to Rumah Kijang were artists whom I have never met, or only met once, hence it would be very difficult for me to really understand what their process was like in Rumah Kijang.

Fredy Chandra: I would like to pose the next question to Agan. Is this exhibiting artwork series Meisjes Uit Indonesië a continuation from your earlier series Mardijker Photo Studio which was shown in the 2016 Singapore Biennale and recently at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart in Berlin? What is the connection between the two series ?

From left to right: Agan Harahap, Miss Toedjillah (Meisjes Uit Indonesië), Miss Ratmi (Meisjes Uit Indonesië), Miss Djoeminten (Meisjes Uit Indonesië), 2018, archival pigment print on paper, 60 x 40 cm, edition 1 of 3 + 1 AP

Agan Harahap: Well, the artwork that was shown at the Singapore Biennale in 2016 is similarly about identity. We are always labeled by what we are wear. For example, I must be an Indonesian just because I am wearing batik or you are a Korean just because you are wearing a hanbok. And of course with the internet and social media, we are already classified into separate communities. Three months from now, there will be an election in Indonesia and people are hating each other because of the separate parties involved. With my artwork, I want to show that no matter what, deep down we are all the same. I am an Indonesian and you are a Singaporean, yet ultimately we are still the same – Asians. Even if I am an Indonesian and you are an African, we are still one big community. So it does not matter if you are Japanese, wearing Indonesian traditional costume. That is the important message I want to send out through my work, and I try to portray it in a funny, light-hearted manner. If you think about it, back in those days, it was impossible for an Indonesian to be dressed in Western clothes, and likewise, a Westerner to be dressed in traditional Indonesian costume.

Fredy Chandra: Thank you, Agan. Gilang, you are an Indonesian based in Jogja who went for a 4-month residency in Rumah Kijang. The period of your residency overlapped with Okamoto-san’s and Kumazawa-san’s. What do you think of the residency and how has it affected you? Could you share with us your ideas and how you came about in creating this artwork?

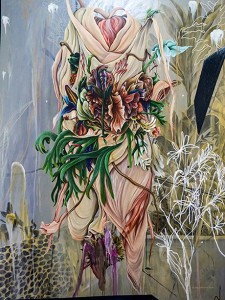

Gilang Fradika: Something interesting that came about from my residency was that I learnt from Ellie [Okamoto] and Mikiko [Kumazawa] to be more disciplined in my work and to get a better understanding of their culture. From then on, I aimed to be as disciplined. My work in this show, titled Kardiak, is actually an artwork done in response to the space of Rumah Kijang. I portrayed Rumah Kijang as a human body with plants sprouting out of it. There are many plants that fill Rumah Kijang and I imagined them to be like a heart – a cardiac.

Fredy Chandra: Okamoto-san, now that you have been in Jogja for some time, how has the experience of living in Jogja for the past 6 months influenced you and your artworks? Your earlier paintings were mostly about Japanese folklore. However, in this exhibition, you have painted an Indonesian man dressed in batik surrounded by tropical floras; also, a painting of a horse that speaks about Jathilan (Kuda Lumping), a traditional performance of Indonesia. Could you elaborate on the choices for these depictions and what influenced you to paint them?

From left to right: Okamoto Ellie, The Inner Fusion, 2018, acrylic on wood 124 x 35.3 x 5 cm, The Reunion, 2018, acrylic on teak wood, 67 x 21 x 6 cm, and Who is on the Horse?, 2018, acrylic on acacia wood, 16.5 x 16.3 x 6.1 cm

Okamoto Ellie: When I came to Yogyakarta for the first time, I thought to myself that I had to get some influence from the local culture because I felt that it is a key aspect of the artist residency programme. For the first two and a half months, I did not begin on any specific artwork, and instead had simply bought a 10-metre wide scroll of paper which I would scribble on every so often. After looking around, there are many different cultural elements, such as the Kraton [The Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat], a palace in Yogyakarta; Kuda Lumping, a traditional dance in which the people danced with a flat prop shaped to mimic a horse and subsequently falls into a trance after chanting a short prayer. There were various traditional cultures found in Jogja, so I kept note of all the things I witnessed, which then became almost like a test of how I was going to output them. Afterwards, when I finished the artwork, which is now exhibited on the first wall nearest to the entrance, I tried to sieve through subjects that were related to Japanese culture – a great interest of mine that I have cultivated for a long time, and is also a fundamental element to my artworks.

Let me speak more about the work Who is on the Horse?. In Japan, there are similarly many festivals or rituals related to horse. So when I watched several Kuda Lumping performances, I wondered and I tried to find out why humans consider horses to have any relationship with the spirit. Thus, the work [Who is on the Horse?] is a result of my attempt to express my interest and wonder on how I felt in Jogja after watching Kuda Lumping.

The idea of the work in the middle, The Reunion, started when I read the story Kancil dan Buaya (The Mouse-deer and the Crocodile), a children’s story originating from Jawa and Malaysia, and is now mainly popular within Southeast Asia. Another story similarly structured was a Japanese folklore of Inaba no Shiro Usagi (White Rabbit of Inaba), a folklore adapted by the locals in ancient times as a myth and still continues on amongst modern day Japanese people. Inaba is the name of the place in Japan that the myth originates from.

At that point I was so interested because prior to that, I did not have many opportunities to think about Southeast Asia and how the culture is deeply connected to Japan. So once I had arrived in Yogyakarta, I was chatting with Bunga, a former assistant to mas Angki Purbandono and also a supporter of all the artists who stays at Rumah Kijang. I mentioned to her about the folklore of Inaba no Shiro Usagi and asked her if she knew anything or any story similar to this story, and that was when she told me the story of Kancil dan Buaya. Upon learning that, I was so moved because the story is very actively shared amongst people and everyone knows that story. I felt like I found a really deep connection between the people of Indonesia and myself, or even with the people in Japan. Looking the clear relationship between the two stories, I decided to create this painting as an attempt to output that experience and put them into a painting on a piece of wood.

Lastly, the painting in which mas Kriyip is depicted—The Inner Fusion—without any explanation it might just seem like a Japanese man putting on a sarong. Before I started my residency term in Jogja, I already had an interest in how people put patterns on their body, or put clothes with specific patterns, and how those patterns affect the human mind. After I came to Rumah Kijang, I learnt that there are various patterns found in batik, and how each of them has its specific meaning or even bears some hope or wish to achieve something – prosperity, medicinal cure, et cetera. After learning about that cultural aspect, I felt that it was really close to interest in tattoo. When people make tattoos, they try to reflect their hopes and thoughts, or their attitude to life and channel that into the tattoo design. So I felt that commonality between tattoo and batik design. I then asked mas Kriyip if he had any tattoo ideas, to which he told me that he did and still does want a tattoo which shows him turning into a plant through the pattern of various other plants. Looking at his daily life in Rumah Kijang, he takes care of the greenery all around the house, and he has become really good at making gardens. He often makes kokedama (moss ball) in his own original way. I thought his tattoo idea was very reflective of his daily life, and thus I asked if I could make a painting of him with a his tattoo idea incorporated—to which he agreed. So I began combining that tattoo idea and batik pattern together to show the relationship between pattern and mindset—something that I have been interested in for a long time.

Hermanto Soerjanto: So is that the first time you have included patterns in your painting?

Okamoto Ellie: Yes, exactly.

Hermanto Soerjanto: I asked because I have seen many of her paintings, but I never did see one with patterns. This one is the first.

Fredy Chandra: Next, we shall move on to Yamamoto Aiko. During Aiko-san’s time in Jogja, you were still very young and had not yet graduated from university. How has the residency benefitted you and were there any influences on your artworks during this period? Please share with us a little more.

From left to right: Yamamoto Aiko, Waver #2, 2018, dye on silk, acrylic 80 x 70 x 3 cm and Waver #1, 2018, dye on silk, acrylic, 130 x 105 x 3 cm

Yamamoto Aiko: Yes, when I went to Rumah Kijang, I was 23 years old and everything I was experiencing then was very new to me. I did not bring any materials from Japan because I wanted to start anew. During the residency period, the people I made friends with shared their materials with me. I actually had not painted for a long time prior to that, since I did not major in painting. However, while I was in Rumah Kijang, there were many painters who were there as well. I was largely influenced by them and we began sharing knowledge about painting, to which I found was very interesting. Eventually, I grew to love painting. But in the 5 months I spent there, I was still quite unsure of what to paint. I painted in anyway that I wanted, simply releasing whatever expressions I had onto the canvas. When I look at it, I did not know what I had accomplished with the paintings.

After returning to Japan, I realised the importance of my time spent at Rumah Kijang. I began to mix my own techniques with the experiences I had taken from the residency, attempting to create something new in my own way. Thus, these new artworks Waver #1 and Waver #2 were done after I came back from the residency. The base of these two works were made from a textile technique I often use. While trying to incorporate a new aspect into them, I decided to include painting. To further explain my reasoning for doing so, I looked at the larger picture of my Jogja experience. Jogja is filled with so much nature and I could communicate with the people even without the use of verbal language, especially since I could not speak English or Indonesian well. Going beyond verbal language, we had shared so much together and I found a certain “aggression” within me. Since being passive had been such a natural feeling, Rumah Kijang might have helped me realised a more unreserved way of expressing myself.

Hermanto Soerjanto: I see, I suppose because many Japanese, especially the women, may be rather private. For Aiko-san, her time spent in Rumah Kijang has actually taught her to be more open and outspoken.

Fredy Chandra: Lastly, since not all the artists are here with us together, I would like to ask Hermanto if there are any other works you would like the audience to know a little more about?

Angki Purbandono, Flower Power Series, 2018, scanography, print on acrylic, lightbox installation, 38.5 x 38.5 cm each (total of 40 pieces), 1 edition lightbox + 1 edition C-print on paper, diasec + 1 AP

Hermanto Soerjanto: I find the works displayed outside in the window display, Flower Power Series by Angki Purbandono to be particularly interesting. The work utilizes photography as a means of archive, and the series will never finish as Angki will continue to produce other flowers. The series is almost like an archive of flowers, but he turned it into an art form—something I personally find very interesting.

Yoga Mahendra, sesuk yen wes aman walesku opo (Later when everything is OK, how can I repay?), 2018,

acrylic on canvas, 140 x 240 cm (triptych, 140 x 80 cm each)

Another work I would like to highlight is the painting by Yoga Mahendra sesuk yen wes aman walesku opo (Later when everything is OK, how can I repay?). His paintings are always overcrowded by people, because he lives in a kampong (slum settlement) where many people are always in a tight space, with one small house shared by 10 people, for instance. Spaces between the houses are also very narrow, hence people in such a formation is often painted. This painting, in particular, explains about the current political situation in our country [Indonesia]. With the election this year, all the political parties are set on stage and fighting one another. Being Indonesian, we are one of the most active societies in the world when it comes to social media usage. As you can see, the supporters are depicted surrounding the platform and fighting with each other—but of course, this only happens in social media.

Fredy Chandra: We have come to the end of the Artist talk. The curator and artists will still be around, so please feel free to approach them if you have any questions. Thank you so much for coming.

—

Hopes & Dialogues in Rumah Kijang Mizuma, a group exhibition curated by Hermanto Soerjanto, featuring Agan Harahap, Aiko Yamamoto, Angki Purbandono, Eguchi Ayane, Fatoni Makturodi, Gilang Fradika, Kumazawa Mikiko, Okada Hiroko, Okamoto Ellie, PAPs (Prison Art Programs), Ryuki Yamamoto, Tsutsui Shinsuke, Yoga Mahendra, and Yuna Ogino will run till Sunday, 10 March 2019