“Where does it all come together as contemporary artists today, that these collages of western style, MTV style, Andy Warhol, mixed with traditional Indonesian folklore, and ideas and stories. How does this all come together? Is it purely a visual picture? Or does it also inform your attitude, your style?”

– Alan Oei

Tune in to our video this week to watch our latest release of Artist Dialogues series, featuring Indonesian artists indieguerillas (Dyatmiko “Miko” Lancur Bawono and Santi Ariestyowanti) in conversation with Alan Oei, director of OH! Open House. In this video, Alan discusses with indieguerillas about their take on consumerism, their background and influences, and their latest project, Murakabi.

Alan Oei is an artist-curator whose work and projects examine the intersection of art history and politics. He is the director of OH! Open House and was previously the artistic director of Singapore’s first independent contemporary arts centre, The Substation.

indieguerillas is an artist duet from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, made up of husband and wife Dyatmiko Lancur Bawono and Santi Ariestyowanti. Dyatmiko graduated in 1999 with a BA in Interior Design, while Santi graduated in 2001 with a BA in Visual Communication Design; both from the Indonesia Institute of the Arts Yogyakarta (ISI Yogyakarta). Founded in 1999 as a graphic design firm, indieguerillas’s philosophy of “constantly in guerrilla to find new possibilities” has led them to become full-time artists in 2007. Through their multidisciplinary works, they talk about their reality as Javanese people who live amidst a wave of global consumerism that demands everything to be instantaneous. Their art making process is an auto-criticism ritual and a method of self-reflection.

Scroll through for the video dialogue, as well as the text transcript below.

Watch the Video:

___________

Alan Oei (Alan): Hello, my name is Alan and I am an artist and curator from OH! Open House.

Today, we are going to be talking to indieguerillas, a husband and wife duo who started as designers, but today are much more well known as contemporary artists who transform and intersect traditional Indonesian culture with pop culture.

I visited both Santi as well as Miko in their house and studio in Jogja this year, but the first time I came across their works actually was an encounter, I still remember – I think it was back in 2010 or 2011, and it was a show that was called “Happy Victims”.

The show had a lot of its roots in Andy Warhol, but it also mixed a lot of traditional Indonesian folklore and symbols and motifs that sometimes I couldn’t understand, but I recognized the things that were Nike, LV, Gucci, sort of the “traditional” brands that we all want, love, and desire. The thing about this kind of luxury consumption is typically we see it as something that is negative, although of course there are people who love all that lifestyle, but as artists, it is unusual to see someone take all of that, and then celebrate it so unabashedly, and you called it “Happy Victims”, which is the best way to describe it. That we actually love being the victims of this capitalist machine that continues to churn out things after things and we want to desire and own all of these things.

So, tell me about that relationship between consumerism and all of these big brands and how does it inform your culture as well as your art practice.

Dyatmiko Lancur Bawono (Miko): Hey Alan, it’s nice to see you again. This is Miko from indieguerillas. Thank you for your interesting questions, and I will try to answer your questions in Bahasa Indonesia because it’s clearly very convenient for me to speak in my mother tongue. I hope it’s fine with you.

First, we want to emphasize that we interpret each of our work as a journal that contains evaluative value for us as the creator of the works.

“Happy Victims” was made in our early 30s. At that time, we began to set aside a little of our income to buy the things we liked as a form of appreciation to the designers of the products. At that time, we did not think further about the ethical or ecological impacts of our consumption patterns.

Exhibition view of Happy Victims at Valentine Willie Fine Arts (VWFA), Singapore, 2010. Image courtesy of indieguerillas.

Meanwhile, on the other hand, we also had access to information about the effects of excessive consumption. Well, these two conflicting facts naturally caused confusion at that time. However, as we always create works according to the situations and conditions that we experience, we turn this confusion into a fuel that drives us to work.

And from there, “Happy Victims” series was born. So, from the title, we can sense that it is paradoxical. Because each of our works has evaluative value, it contains self-criticism for ourselves. So, the series “Happy Victims” was eventually made into a study material.

The output of the study can be seen some time later in the collective project Murakabi, where instead of celebrating consumption patterns, we celebrate patterns of responsible production, distribution, and consumption.

Alan: Your background is in design, and I remember that you said you started with designing music covers for your friends, and later on you guys also published your own indie magazine. And so, where does it all come together as contemporary artists today, that these collages of western style, MTV style, Andy Warhol, are mixed with traditional Indonesian folklore, and ideas and stories. How does this all come together? Is it purely a visual picture? Or does it also inform your attitude, your style? And what are the underlying thoughts behind all of these that make up the core of who we are today as artists?

Miko: This will be quite a personal question, perhaps. We grew up when Indonesia was ruled by the New Order. The New Order liked to make statements about always preserving the values made by our ancestors. On the other hand, during the cold war they also opened up our country widely, allowing the flow of global or western culture. I happened to have a strong enough access to these two things.

So for example, I could be tuning into a wayang kulit (shadow puppet) radio show, and then went straight to listening to a song from Duran Duran. These things took place simultaneously in my formative years. So you could say that my memory is filled with things like this. It might be natural for me when these things reappear simultaneously in the works of indieguerillas.

In the beginning, what we made stopped at the visible appearance of the work. But as I said from the beginning, each of our works has a self-criticism characteristic for us. Over time, we try to continue to deepen the knowledge of what is around us. In this case, about Javanese culture, all at once without losing interest in global cultural issues.

Then, about the question whether these things influence our attitude or style? The answer is: Yes, they do. We always see that through the work of indieguerillas, we learn to be happy being ourselves. Accept ourselves happily. We rejoice to be Javanese persons in the midst of a global cultural arena. So, speaking a universal language with a thick Javanese dialect, not to raise the issue of identity politics, but merely to enrich the atmosphere. Contributing positively to the beauty of the planet which has been, and will always be beautiful. I suppose that’s all.

Alan: You have in the last few years embarked on a very ambitious project, moving away from the kind of gallery and art fair-centric way of thinking about both creating and producing and presenting artworks.

You started this thing called “Murakabi”. Could you tell us more about that? Tell us about your collaborators, who are the people producing things and how are the works and projects actually being presented and remembered, and not only that, have a life of their own thereafter?

Santi Ariestyowanti (Santi): Hey Alan, thank you so much for the questions. Now it’s my turn to answer the question about Murakabi. I hope you don’t mind if I speak in Bahasa.

Before speaking about Murakabi, I will go back a bit to 2014, when indieguerillas made a painting [Fragmenting Incomplete Memories (2014)] that talks about the life of urban people who had been uprooted, specifically uprooted from their connections to the natural surroundings. At that time, the work was exhibited in Art Basel Hong Kong.

Then in 2015, when we became the commissioned artists for ARTJOG. In one of our installations [Taman Budaya: Green Box (2015)], we made a bicycle that looked like a house, with the front of it made to look like a wagon planted with rice and some vegetables. It was an expression of our observations, that in the vicinity of our house there has been a decline in agricultural land, which is increasingly displaced by the presence of housing.

Taman Budaya: Green Box, 2015. Photography by Riki Zoel, image courtesy of ARTJOG and indieguerillas.

During this time, there was also a collaborative work between us, Lulu Lutfi Labibi, and Ari Wulu. We made a show entitled “Datang Untuk Kembali (Arriving to Return)”, which globally talked about fashion waste that we reprocessed into upcycled works. At that time we were invited by Prof Ute (Meta Bauer) from NTU CCA Singapore to make a performance in 2017.

Datang Untuk Kembali (Arriving to Return) by indieguerillas, LULU LUTFI LABIBI, and Ari Wulu. Presented at NTU CCA Singapore as a part of CITIES FOR PEOPLE NTU CCA Ideas Fest 2016/17. Photography by Eandaru Kusumaatmaja & Ig Raditya Bramantya, image courtesy of indieguerillas.

Datang Untuk Kembali (Arriving to Return) by indieguerillas, LULU LUTFI LABIBI, and Ari Wulu. Presented at NTU CCA Singapore as a part of CITIES FOR PEOPLE NTU CCA Ideas Fest 2016/17. Photography by Eandaru Kusumaatmaja & Ig Raditya Bramantya, image courtesy of indieguerillas.

And then in 2019, we received an opportunity to take part in a residency at the Akademie Schloss Solitude, also through the invitation of Prof Ute. We used this time to relearn, to contemplate on our work process so far, to re-examine the almost 20 years of indieguerillas’ process.

From there, there was a moment, towards the end of our stay, we gathered with Prof Ute, who apparently at that time had returned to Stuttgart, together with the director of Solitude, Elke aus dem Moore. We chatted during lunch. There was an interesting topic that came up, in essence, that we have to make something, because artists cannot just make beautiful works while we are aware and we understand that this earth is sinking. So, where is the responsibility of the artist, or the role of the artist, towards natural conditions?

L-R: Elke aus dem Moore, Dyatmiko “Miko” Lancur Bawono, Prof Ute Meta Bauer. Image courtesy of indieguerillas.

L-R: Prof Ute Meta Bauer, Yvonne P. Doderer, Elke aus dem Moore, Dyatmiko “Miko” Lancur Bawono. Image courtesy of indieguerillas.

From there we felt we had to make something which—well, we were moved by those words, and wanted to make something based on that experience. The results of our six months of reflection in Stuttgart, in the end we felt that all this time the work of indieguerillas has been on the plains of ideas and symbols, and still has not touched the real lives of everyday people.

Therefore, when ARTJOG offered a collaboration between indieguerillas and Singgih Susilo Kartono—he is a world-class product designer and an activist of a locality-based creative movement—we thought we had to create a work that must be in contact with everyday life. When discussing with Mr. Singgih, we felt that this collaborative work must be supported by various parties, and we thought of inviting Lulu Lutfi Labibi, a fashion designer; then Agung Satriya Wibowo, an activist of sustainable food culture; Adamuda, an advertising practitioner; and Sindhu Prasastyo, an upcycle activist. From our subsequent conversations, we thought of making a warung (small shop).

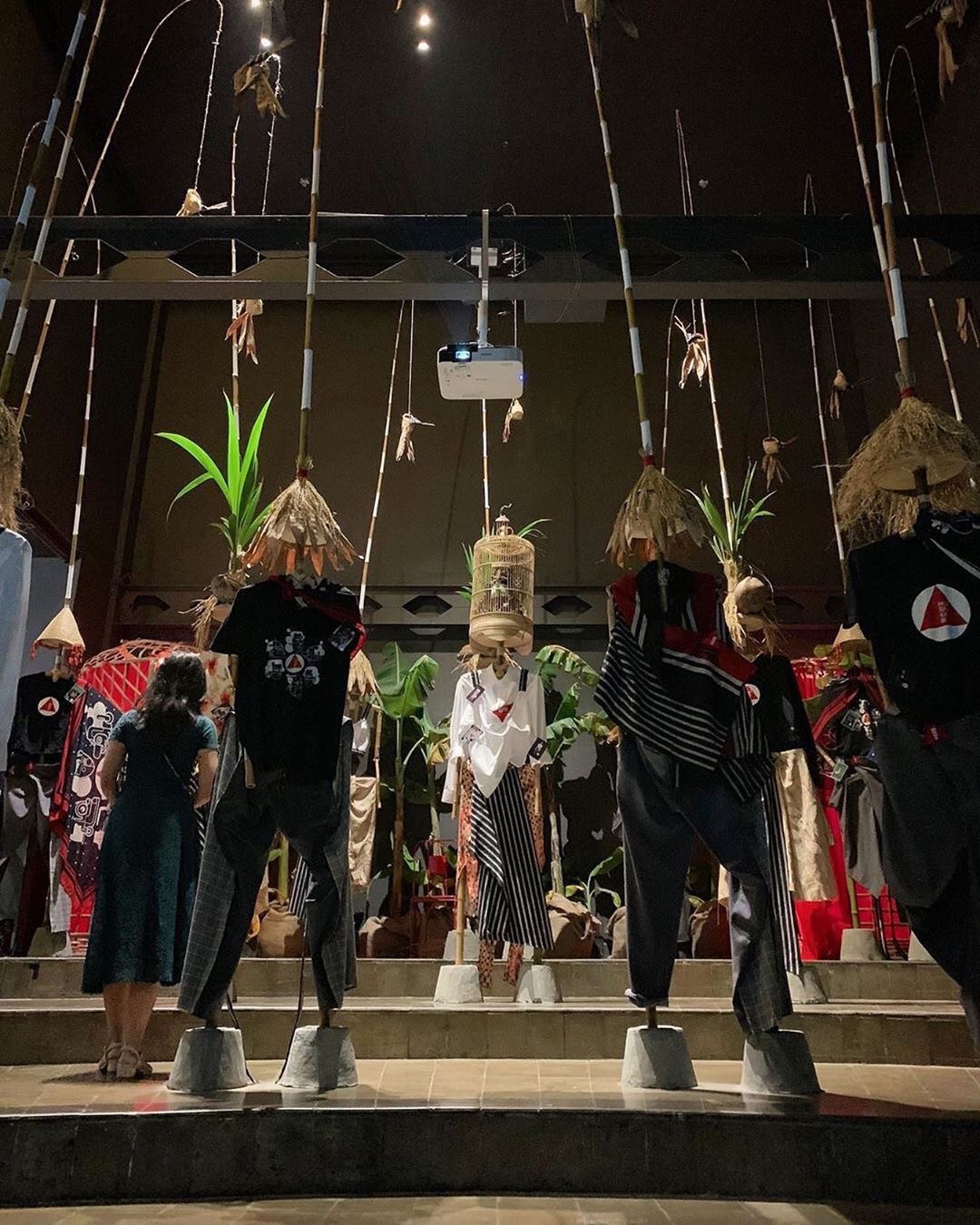

Exhibition view of Warung Murakabi at ARTJOG MMXIX, Jogja National Museum, 2019. Image courtesy of ARTJOG and Murakabi.

Exhibition view of Warung Murakabi at ARTJOG MMXIX, Jogja National Museum, 2019. Image courtesy of ARTJOG and Murakabi.

Exhibition view of Warung Murakabi at ARTJOG MMXIX, Jogja National Museum, 2019. Image courtesy of ARTJOG and Murakabi.

Exhibition view of Warung Murakabi at ARTJOG MMXIX, Jogja National Museum, 2019. Image courtesy of ARTJOG and Murakabi.

Exhibition view of Warung Murakabi at ARTJOG MMXIX, Jogja National Museum, 2019. Image courtesy of ARTJOG and Murakabi.

Then the name Murakabi was chosen to reflect the spirit of this movement. It is taken from the Javanese language which means ‘useful for many people’, and also means ‘adequate’ or ‘sufficient’. Murakabi can be translated as a creative movement based on mutual cooperation to realize the sustainability of life by making locality and independence its foothold.

Alan: We’ve come a full circle now, from “Happy Victims” to a complete opposite, which is thinking about the community – not only to be able to distribute, but also to be able to produce and own the creative rights to some of their own goods, and that in this scenario, the artist is not really the creator, but the person who enables and facilitates, so that the creative production can continue on and on, with or without them.

So, tell me a little bit about what has happened in Jogja over the last few years, and how that perhaps has shaped your thinking?

And of course, please tell us about your hopes and your aspirations for “Murakabi”, what do you hope it can become in say five to ten years’ time?

Santi: The main spirit that was built by Murakabi is to activate the usefulness of the potential of natural resources and creativity in the closest social space, to unite them into a common force. So in accordance with the name of this group, we are trying to be guerrilla, moving together with the power of creativity to continue making this shared space sustainable. So in the future, Murakabi as a movement will be open to participation and collaboration with various parties, so that the concerns of Murakabi will continue to be present as part of our lifestyle, and eventually will become our life force.

Some communities and producers that joined us as vendors in the Murakabi shop were Agradaya, Burung Hantu Sahabat Petani, Dapur Mooi, Depoide, Giriwangi, Kebun Kita, Keripik Bonggol Pisang Al-Barik, Koperasi Edukarya Negeri Lestari (KEN8), Kopi Sulingan, Krya Sorghum, Legoroso, Lokaloka Kitchen Lab, LULU LUTFI LABIBI, Mbale Jampi, Omaina Smart Cookies, Sage Livingfood, Sapu Upcycle, Sekolah Pagesangan,Tahu TOELEN, Tempe Tego, and Una Natural Care.

Now in 2020, we want to make a real Murakabi shop, not only as a part of ARTJOG, but a real shop. Well, our first shop will be in Minggir, sharing the same location as Agradaya, in the Minggir area, Sleman. There we will form a shop that really strives to meet the needs of the local residents.

Murakabi Minggir shop is present to meet the needs of the surrounding community and also as a place for local farmers, artisans, and local producers to collaborate with Murakabi shop. Of course, with the Murakabi shop in Minggir there will also be more exchanges of knowledge and hopefully this will lead to something else in the future. So actually there are several types of Murakabi, and this type will vary too. So Murakabi Minggir will be one of the examples of our next activity.

This Murakabi shop can also function as a cooperative. So our idea for the future, there will not be only one or two Murakabi shops, as the shops will be present based on the needs of a location or place, where they require quality products with environmentally friendly standards that are also very affordable for the surrounding community. And don’t forget that there is the role of art which makes things a little more different, as it brings a special approach to the patterns of cultural and social activities.

I personally consider that the concept of a small shop that was present in my memory and a form of cooperative as a concept, at that time, was very good, in the era of the New Order. But where the application was not going well, we felt that this is where art can play a part. Either as—from art we can see a new potential that is different from the previous perspective, or how to process things to be more flexible, softer, and more beautiful. So it uses the power of taste, intuition, imagination, so that these concepts that are actually good can indeed be brought back, revived, in a more interesting form.

In the end, we hope that the function of the designers and artists in the Murakabi shop community serve only as a trigger, as an example, as a catalyst so that the wider community has an idea or has friends to work with, and has more enthusiasm. That everything can be presented with a different taste. The rest, its sustainability will depend on the wider community, especially from the surrounding local community.

Another hope for Murakabi in the future is, Murakabi as a place to exchange knowledge, especially past knowledge from ancestors, knowledge from the village, knowledge from the community that is actually required as basic knowledge for us to survive. So bringing the humans closer to nature, wiser, more able to flow with the motion of the universe.

Our hope for Murakabi in the next few years, we hope that Murakabi will exist in various places with different cultural backgrounds. So the composition is: there are designers, artists, environmental activists, farmers, craftsmen, and many more, including maybe scientists. We gather together with Murakabi, and of course there will be various unique versions of Murakabi, according to their respective regions.

So there is no standard to what Murakabi must be. We exist out of necessity, Murakabi is not born out of a very rigid concept. So in the future, how it will develop will also flow as needed.

—

Copyright and Image Credits:

© indieguerillas, ARTJOG, Riki Zoel, Eandaru Kusumaatmaja, Ig Raditya Bramantya, Murakabi, Budi Laksono, and Mizuma Gallery.

Transcribed and translated by Theresia Irma.