“The aesthetic quality of your works, the beauty, is inherently linked with that fear of impending loss through the fragility of medium and handling in craft. Can you further talk about the colouring and dyeing process that is at “the risk of ruining the paper because it is quite thin”?”

– Susie Wong

For this weekend’s artist dialogues with curators, we have artist Ashley Yeo in conversation with Susie Wong.

Susie Wong is an artist, curator, educator and art writer in Singapore. Wong has curated, and/or co-organised and/or participated in several solo and group Personae I & II (1994, 1996), Women Beyond Borders Singapore (2001), Hope (w.a.p.) (2001), My Beautiful Indies (2013), [after image] My Beautiful (2014), Take Care of Me (2018), [The Machine] Contemplating The Body (2014), Precious (2004) and Histories Identities Technologies Space (2001). Wong has also written for numerous publications on art since the late 1980s, and is a member of AICA (International Association of Art Critics- Singapore Chapter).

Ashley Yeo graduated with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts from the University of Arts London, Chelsea College of Arts, London, United Kingdom in 2012 and a B.A. in Fine Arts from the LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore in 2011. She has participated in numerous exhibitions in Singapore, Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom, and United States. Yeo was the first Singaporean artist to be shortlisted for the LOEWE Craft Prize, London, United Kingdom (2018). Revolving around themes of lightness and slowness, Yeo’s practice is built upon reflections on the accumulations of hedonistic culture and alludes to the soft and fragile. Her paper sculptures explore geometry, precision, and the spiritual power of simple materials. She is currently interested in maintaining a relationship with nature.

___________

Susie Wong (Susie): Ashley, thanks for sending me the images that include sketches and work-in-progress. Would you like to elaborate on some of them?

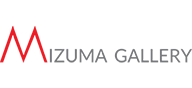

Ashley Yeo (Ashley): The sculptures I am making range from 5cm all around to 15cm max. As you can imagine they are quite small. I’ve included colours of light gradients and used pigments, glitter on the paper. They are all hand-dyed. My largest papercut piece so far is titled a soft spring (2020). It measures 44.5 x 44.5 cm and is circular in shape. I will provide the background of this work of gradient paper as well to bring out the work. I have yet to complete that; I am afraid most of these are still ideas till I resolve them. I have already completed parts and pieces but yet to join them to a full sculpture. The sketches that you see are the shapes that I am trying to complete.

I use colours that try to evoke peaceful moods or natural colours, although the pigments are not naturally derived but artificial. Natural pigments usually involve much bigger particles, and when I apply it on paper, they often tear the paper surface. Thus, I had to use artificially-derived pigments, which bothers me, but technically I have not resolved it yet.

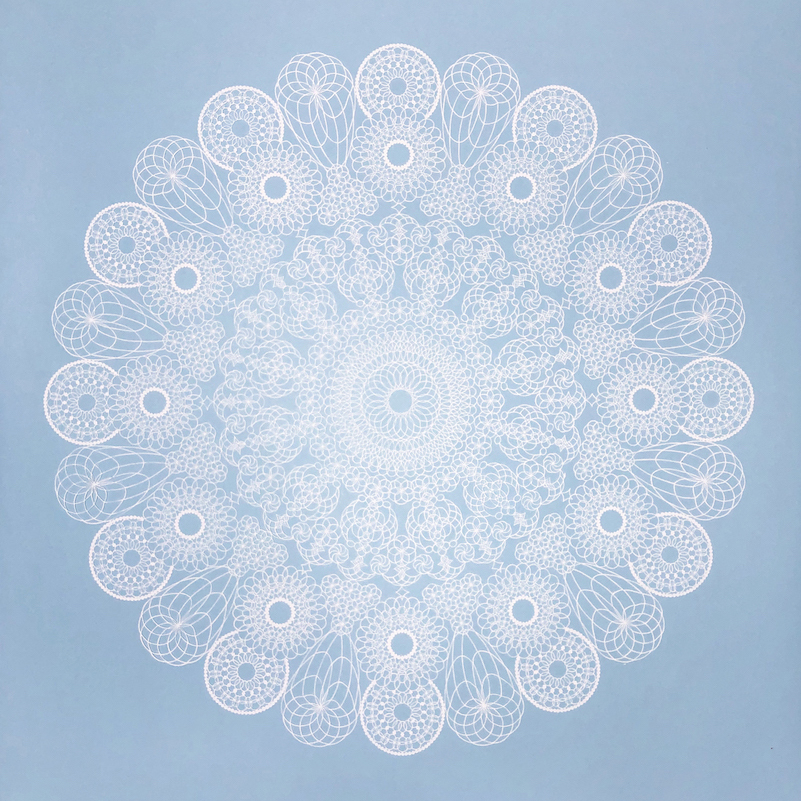

I’ve also included a 3D rendering of an installation: it will be made from white porcelain. It’s meant to hold multiple, repetitive forms to create an illusion between petal rain and waterfall. Each singular form resembles a petal and a droplet.

Conceptually—I think my work began initially for myself as a recluse in terms of my reacting to what is going on in the world, my trying to find a quiet and peace from my own anxieties which expanded into focusing on a kind of craft and taking time to make things. To generate a quiet experience for the viewer through observing the small objects.

I’ve always been drawn to vastness and landscape—thus my trying to complete an installation this time on a much larger scale. I’m still interested in drawing though I’ve yet to resolve the works. I’ve also shared with you PDFs of drawings I was doing but did not complete as technically I’m not satisfied with them but I was also stuck on the composition. I just wanted to share where my sensibilities led.

I stopped creating the black & white drawings of landscape, as I felt that to an extent they were limited and it felt too small for me to try to capture the vastness on a small piece of paper. Over time I felt that I needed to move on from the drawings as they appear very flat to me. But I still feel much keenness towards drawing and love the medium greatly. I draw flowers regularly but don’t think they can provide a contemporary and critical perspective currently, which makes me feel that they are not enough.

The title I’m thinking of for my upcoming show is “gentle daylight”, trying to encompass the small and the soft, the slow and the frail (materiality, visually, as experience, moods).

Susie: What inspires you to think of “gentle daylight”? In a sense, I understand your linking it with “the small and the soft, the slow and the frail (materiality, visually, as experience, moods),” but I am wondering about whether it is about the time of the day, or perhaps a place? Or any thing?

Ashley: Yes, “gentle daylight” also refers to the period where it’s starting to get bright, like dawn. I think it’s a little like warming up, a bit of it is to try to convince one to look towards a new day, maybe the idealised vision of what a new morning or a new day can bring.

Susie: What are you reading lately? Does any, do you think, help as an inspiration to your work?

Ashley: I was reading The Impermanence of Lilies by Daniel Yeo most recently, as well as Loss Adjustment by Linda Collins. I can’t say they contribute much directly, but between the poetic and cryptic prose in the former and understanding the aftermath of a daughter’s suicide (latter book), I think that’s where my mind wanders to nowadays.

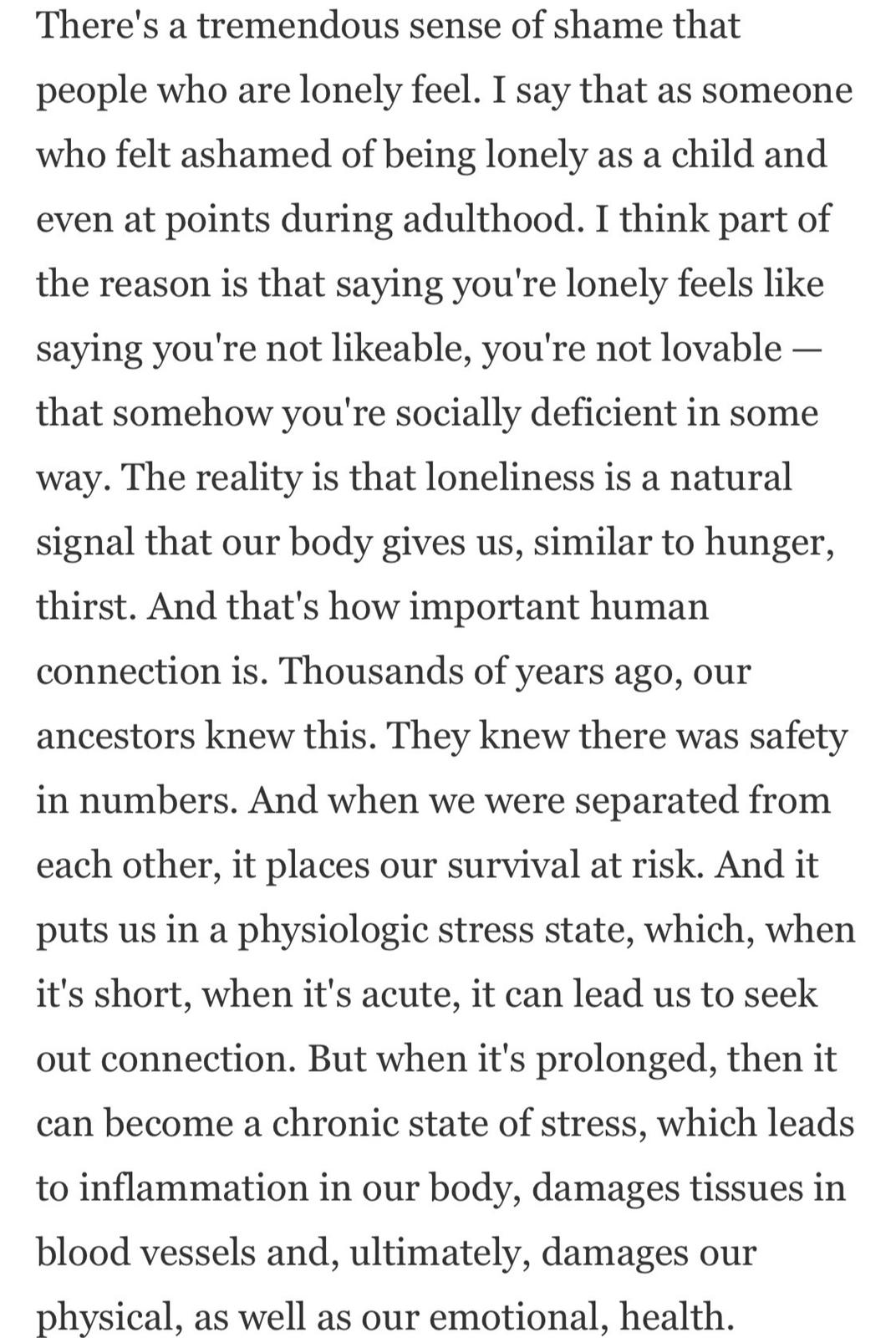

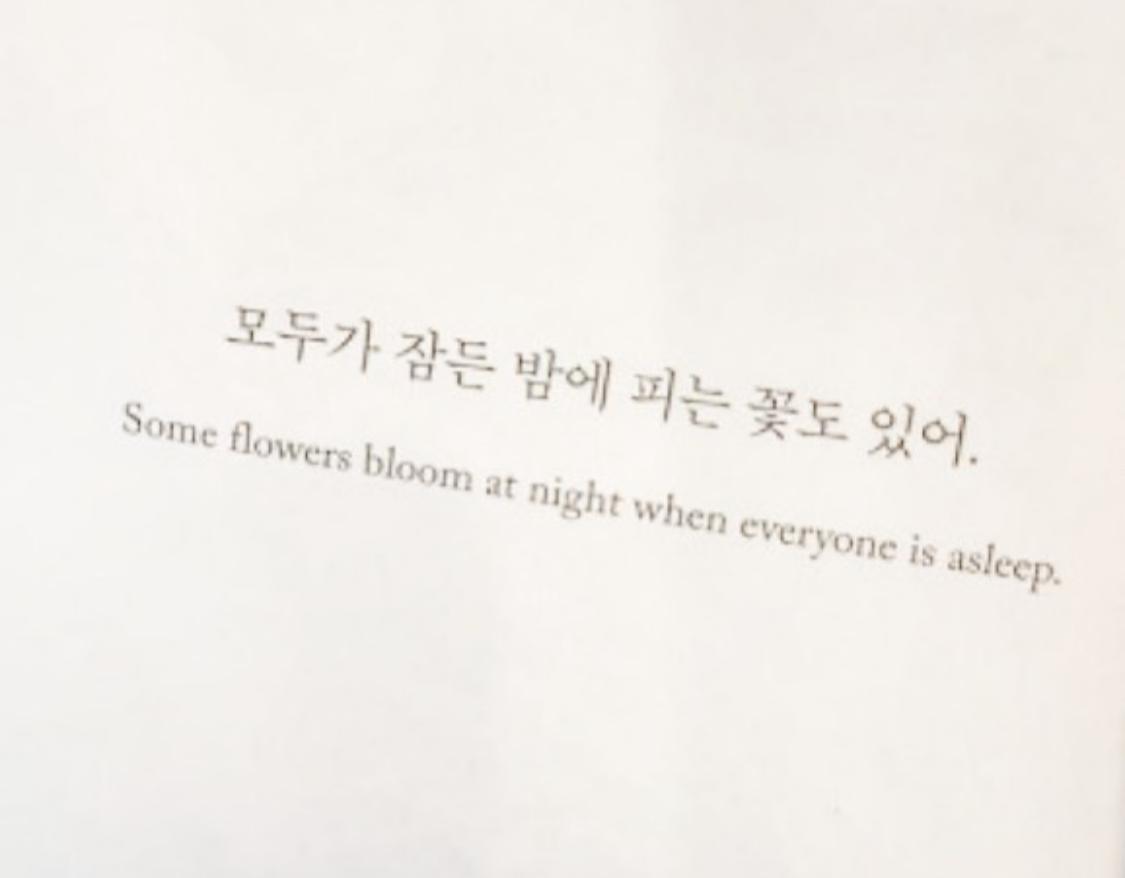

Susie: I think you are already setting the tone to an insight to your work. There is a recurring theme of corporeality, of fleetingness, and dare I say it, even in the facing-off of death – which is suggested even in the titles. Can you share some bits of Yeo’s The Impermanence of Lilies and Collins’ Loss Adjustment? But please don’t feel confined to these; you can share other meaningful literature or works that clunk around in your head. What is it about the aftermath of a daughter’s suicide that have you pondering it?

Ashley: I think suicide in general for me is… Maybe a way to recognise desperation or very deep pain. And to know someone has done it, that it was too much, that they have viewed the world as very unkind, their existence as very unnecessary… I think it’s very heartbreaking. Someone else. So young. Or successful, or, so unexpectedly… To never recognise help until it’s too late, or being unable to help because one lacks the mental facility to do so. Here are a series of quotes/texts I have saved recently. I hope they can perhaps give you more insight to what resonates with me.

Susie: Thanks for the batch of quotes/texts, they are helpful in eking out some themes in my looking at your work. We are left with this subjectivity, of the terrible/beautiful: what would be inane to try to describe this resonance or recognition of suicidal despair, and loneliness, or yearning to connect, except through poetry or art. You describe yourself as “recluse” and you use Princess Mononoke in your Whatsapp profile (let me know if you prefer not to go there). A recluse and yet a kind of warrior. Facets of Ashley. You can comment here, or not.

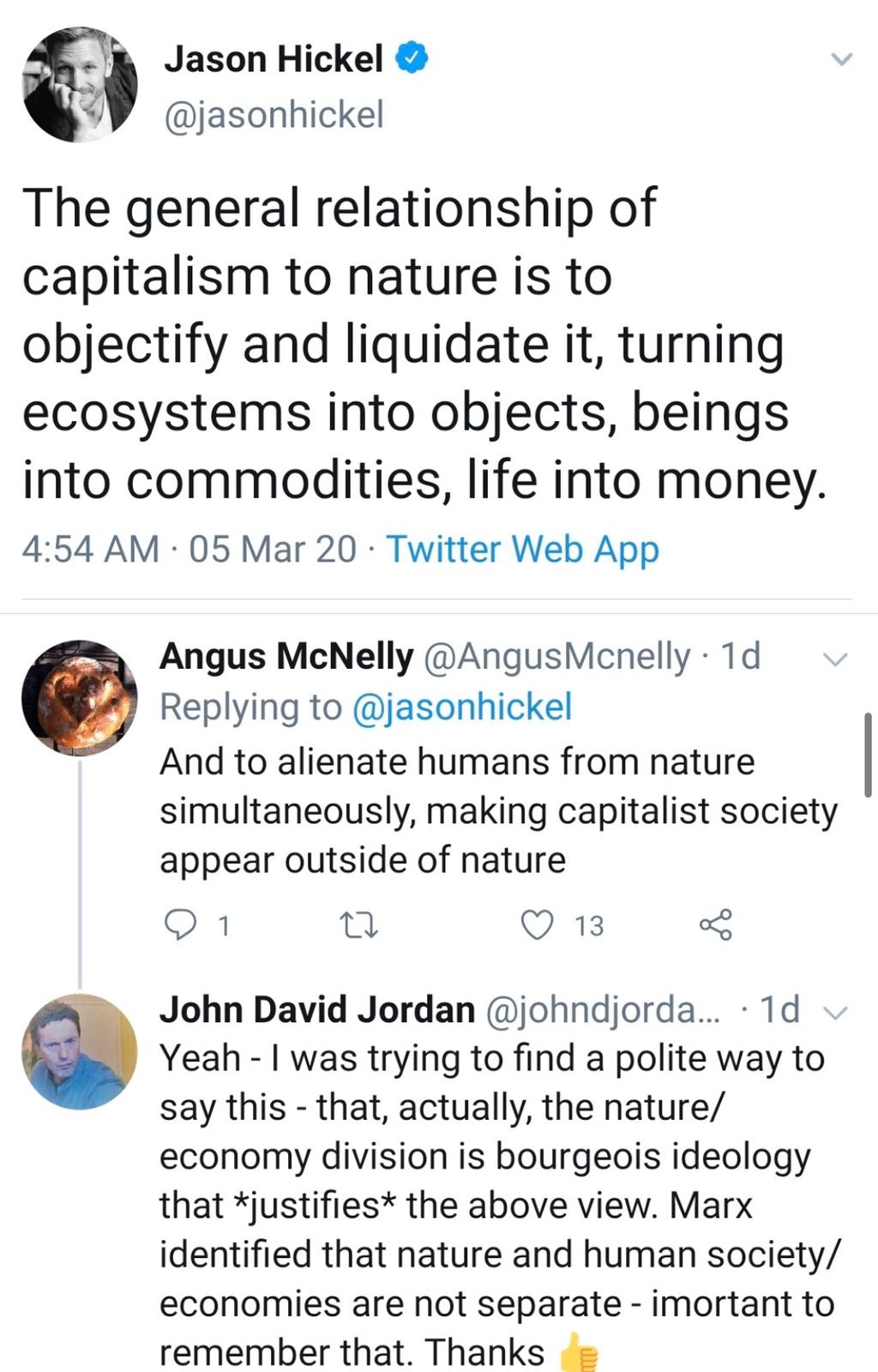

Ashley: That’s a nice observation. I think I admire the character a lot, Princess Mononoke. To live closely with nature, to face wars, to play an active role towards what she wants to protect, also, that she could find someone equally admirable, who can love her and find her beautiful and understand her disdain towards the humans and accept her. I won’t say she’s a representation of me, but I look up to her as a character even if she’s fictional. I lack courage and strength; maybe even lack understanding and have a lot of fear of partaking in any active issues. I have come to accept that’s how certain business and institutional structures at play, their emphasis on profit and how they preserve certain powers or hierarchy. This came to me as I thought about your word “warrior” as much as Princess Mononoke is one, and a very strong one. Even if I have angry feelings towards various exploitations by capitalism, I am very much one of the small cogs in the system because I want to survive and prosper, even if I dislike the conditions. I think that leads to a lot of internal conflicts and anxiety within oneself, distrust towards oneself. The life of an artist can be full of pain and pride.

Susie: Of despair, you shared a quote by Wu Tsao: “vague poetic feelings/ that I cannot bring together.” I read through your batch of quotes/text, and ended up digging my own, so much internal monologue. I need to bring it back to beauty. Clarice Lispector comes to mind (Aqua Viva): “My ravings suffocate me with so much beauty.”

Suffocate as in – I imagine – the minute breath-holding act of cutting, the precise calculations of ellipses and circles that you employ in your craft, speaks of total immersion in a more objective dimension— precision, patterned, repetition, mechanical. It is obvious from what you have said that this helps you “find a quiet and peace from my own anxieties which expanded onto focusing on a kind of craft and taking time to make things.” But the intensity of it, does it become an almost oppressive activity? How do you reconcile it? There is a text/ caption that suggests a “spiritual power of simple materials”. Can you explain more your reason for your choice of paper, and more recently porcelain, as a medium?

Ashley: I won’t say I enjoy melancholy and they don’t drive my work (I cannot work in a depressive state), but I also recognise that my works have all along held something vaguely sad, or vaguely dark quality and I would like to continue to keep it that way. It’s not pointedly so, but I think it’s the vague presence of it that allows me to show my own dissatisfaction towards the world as well, or at least, certain structures of it.

It can be quite difficult to work at times. My works demand a lot of concentration and perseverance to complete a piece. Sometimes I question why I am doing so—but the gallery wants to fill the space, requires more work, etc. Honestly, I have not much desire now to make more papercut at this moment. As much as I appreciated where it has led me, in all honesty I want to return to drawing. But I have spoken to two curators who have no interest in developing my drawings currently, for two separate exhibition possibilities. Of course that response directs what I make. It is another conflict between what I want to make versus what is expected of me as an artist. It started out as peaceful, and as a passage for me as an artist, as a dedication to craft, but now I tire of it. It doesn’t provide me with anything new. I think this is more personal rather than contributing to the content of this. But when I consider colours and surfaces, that gives me slightly more anticipation towards what the works will look like, I feel more excited again as I test colours and pigments and particles. All this can be very exhausting; I am still new at colouring and dyeing paper, at the risk of ruining the paper because it’s quite thin, but I think that’s all part of the process. Rarely do I find enjoyment when I cut the paper, when I make the calculations, when I have to resolve a joint with the patterns so on—I still do, just quite rarely. I have not reconciled with it yet.

Susie: Going back to terrible/beautiful, one of your quotes also refers to beauty and its interlink with violence: a “half brutal reality” and in the context of today’s expectations, the image, “how we grow accustomed to painful procedures until beauty is pain.” Am I right to suppose these passages relate to social expectations of a ‘woman’s beauty’ as a context? Am I right to see some feminist stance in your saved quotes/readings and the resistance to the oppressive male-centric world? What are your own thoughts on this and how does it bear down on your work?

Nature and flowers. There is a context in your batch of quotes to your position on Nature. Should I even put it in upper case? Is the presence of the floral or flowers (natural landscape, water, river) in your works a presentiment in these contemporary times, especially in the light of a devouring capitalism? What is Nature to you?

Ashley: I used to think about violence (towards the self mostly) and also, beauty standards that can be painful to keep, tattooing etc. Yes, very much feminist. I would defend any girl who gets teased for not shaving or not putting makeup or not playing a role man want them to play, but of course there is so much more that I am limited at. I still contest certain issues within myself, societal expectations of women (especially nearing 30… other people’s comments, etc.) I have thought about it a bit, but artistically I don’t think I have been successful in putting such content across. Perhaps not directly. My own insecurity and worries as I make my work seem to stem from doubts that my works are not intelligent enough, not critical enough. But I still make them, because currently I don’t know anything else.

Here is a small excerpt above from my written proposal, as I was trying for myself to understand my own works. I won’t really say I am a big follower of the OOO (Object-Oriented Ontology) theoretical structures, but it did give me a certain basis of how I understand my own interest towards objects and making art objects. I tried to address some questions which I have yet to resolve or reconcile:

How can aesthetic experiences through objects of the small, disregarded and intimate be a conduit for moments of equanimity, particularly to address the diminishing moments of contemplation brought about by the digital era. To expand on the study of objects and their aesthetic qualities, how objects can generate space for contemplation through aesthetic experiences and allow for re-examination of how one consumes experiences.

1) Will exercising Chinese aesthetics through objects offer better accessibility to an aesthetic experience? 2) How can we invite contemplation and recover equanimity through art-objects? 3) To consider alternative possibilities to modes of display and exhibitions based on Chinese and critical aesthetics.

While Spuybroek dismisses natural texture that is inspired by Japanese aesthetics Wabi-Sabi and calls it “weak decoration”[1] because he sees that the material has more responsibility than the design and has no relationship between pattern and design. I believe that natural textures can contribute to generating sparks in the dialogue between objects and their qualities. In Chinese aesthetics, the term ‘雾里看花’ [wù lǐ kàn huā][2] (appreciating flowers in the fog) values vagueness to create possibilities of form, where the unknown and inarticulate becomes a quality. Metaphorically, is veil not like a fog? This also returns to my interest in the beauty of concealment and the unknown in Chinese aesthetics.

By considering surfaces as objects, we are able to consider a metaphorical volume and create a deep surface[3]; it consists of the depth of space and flatness of a surface and refers to charging surrounding space by adding atmosphere that immediately draws everything in. Object-Orientated Ontology (OOO) refers to this quality as Sensual Quality, though I would prefer to refer to it as energy[4]. Jane Bennett believes in energy as the one matter that makes things seen and unseen and that objects are able to generate energy and continually do things. It is similar to Walter Benjamin’s term aura[5]. By extension, the energy can be an unknown, as something difficult to articulate and invisible. I would like to expand from Bennett’s ontological ideas between humans and things, a term she refers to as vital materialism, to consider the invisible qualities of artworks and how we can manifest energy from materials and forms as objects to create an aesthetic experience.

The unknown and mystery of artworks has been well discussed, though sometimes difficult to specify and articulate. The inability to articulate the special quality becomes part of the artwork. From D.H Lawrence’s a third thing[6] to Willi Baumeister’s The Unknown in Art, their words became a defence for the unknown as a natural force that generates an imagined experience or exchange. Lee Ufan refers to the experience of the personal exchange between the artwork and viewer a secret dialogue[7]; how the artwork is experienced and how the viewer contemplates their experience with the artwork becomes personal and intimate. The secret dialogue allows the viewer to enter a space of contemplation and in return, initiating a moment of slowness.

[1] Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2016), p94. [2] Zhu Liangzhi, Quyuan Fenghe: Zhongguo Yishu (Hefei: Anhui Education Publishing House, 2006), p51. [3] Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2016), p58. [4] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (United States of America: Duke University Press, 2010), p 22. [5] Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (London: Penguin, 2008) [6] “Water is H2O, hydrogen two parts, oxygen one, but there is also a third thing, that makes water and nobody knows what that is.” D.H. Lawrence, Pansies, 1929. [7] Lee Ufan, The Art of Encounter (London: Lisson Gallery, 2004), p46.

I’m a big fan of Rei Naito’s works – perhaps why I am trying to expand the scale of my own works as well. I appreciate natural textures a lot, either to accentuate them with a little colour, or to present them quite pristine (paper or porcelain), my experience of such surfaces is very precious to me, that I could see beauty in them and I wanted to share them, through my technical applications; could I continue to share their beauty (of the material and surfaces) with the viewer?

Of course it is not so much of Chinese aesthetics currently, I have yet to apply them as I would like, but I think that’s why I enjoy the colours and particles of pigments because it brings me a step closer to the materials, also to reflect the affinity Chinese aesthetics have with nature, how they portray birds and flowers, their mountains and bodies of water. I love flowers very much, and always always wanted to be closer to them. I draw them a lot, maybe as a way to escape from what I’m doing as well. But I have only taken a very touristy approach to them; I have yet to be uncomfortable in nature. I think I yearn to look at nature from the window, not be part of the brutality of nature. I want to at least preserve what remaining yearnings I have towards it, to present it.

I hate the disregard towards nature that big corporations show. But the power of a few is nothing compared to their influence… How can I continue to protect nature? I’m not sure, even when I do change my lifestyle and habits, or be more conscious, only to see in recent research we really as individuals can’t really do anything without stopping or at least limiting what big corporations do. I digress, but yes, nature to me is vastness, and freedom, beauty and silence, not necessarily peaceful or comfortable, but the potential that it can be.

Susie: Thanks for sharing, many touchpoints. Yes, we are always intrigued, drawn to the “mystery of artworks,” and the vagueness of feelings. And a lovely phrase “a secret dialogue.” It seems to run counter to what we are doing now: to pry open and to try to put in some form of context, when contemplation is subjective. Can you let us know the source of the excerpt from the proposal that you included? In it, you mentioned Chinese aesthetics, which perhaps provide another context for thinking of your work; it would be necessary to know the scope of this thinking, perhaps just what and how it links to equanimity.

Rei Naito’s work, in which light plays a major and necessary aesthetic element, brings me back to your title under consideration, “gentle daylight”. For me, this points to the in-betweenness of things, the flailing areas, between the concrete and the dream, the waking-from space.

Ashley: My research on Chinese aesthetics comes from a Mandarin book by Zhu Liangzhi, Quyuan Fenghe: Zhongguo Yishu on Chinese Art in China. It is a proposal I wrote in order to attempt to understand my own context for my artworks and theoretical interest, in the hope of reconciling them. I wonder if it’s helpful at all?

Yes, I like the concept of daylight a lot, if I can even call it a “concept”. I have not actually tried to play with light as much, as light sources for me are ultimately artificial light, but I am always attracted to daylight or “natural lighting” in architectural spaces but I myself have not utilised that in my own works.

Susie: I note the importance of the material for you; it is important to contemplate the work, and you have made effort in generating and allowing for this contemplative experience. How have you played with light in your work? Has the development of dying in colour and introduction of glitter changed the way you think of light in your work?

The aesthetic quality of your works, the beauty, is inherently linked with that fear of impending loss through the fragility of medium and handling in craft. Can you further talk about the colouring and dyeing process that is at “the risk of ruining the paper because it is quite thin.”

Ashley: Yes, the amount of glitter I used in the work becomes quite subtle, and lighting becomes necessary. I think it is something I can tackle more straightforwardly when I have placed the work in the gallery. I don’t think it changed my way of thinking about light per se, but that I am able to apply it more in practice, that I can try to come closer to what I want to achieve, through playing with colours and materials.

The process: I start with preparing the colours from pigments, the binding agent is animal glue (deer glue if that matters) — I use it because I have it available, but also it is relatively long lasting. Sometimes I mix with readymade watercolour to have more depth in the colour. I also add the glitter particles at this point. I then apply the colours in multiple layers, but each layer is applied after the previous layer is semi-dry to avoid disturbing the initial layers. I repeat on the other side until the paper is saturated as desired. I then press the paper between wooden blocks to remove any warping. Usually long fiber papers like Japanese paper (washi such as kozo paper is very suitable) takes the colour very well. But those papers are unsuitable for cutting. The papers that I use for cutting are too thin, and usually have a kind of coating that does not eat the colour well, and often break down due to the amount of water I apply, or dries very unevenly such that the paper is unable to be pressed (unfortunately I do not have a commercial press that perhaps would have helped a great deal in this process). Regardless, it is a long and slow process for me that can take a few days just to prepare the papers. I am just happy with a few successful pieces, which I do have and will use them for the upcoming show.

Susie: I am interested in your wishing (as you expressed in your proposal) “to address the diminishing moments of contemplation brought about by the digital era.” What are your concerns about contemplating the art object in the digital era?

Daylight is not a singular matter without its context of physical space, the world, relationship of the earth to the sun. Likewise, for the digital culture, daylight and space are replaced by the lit screen. May I ask how much do you rely on or don’t rely on (as in resist) digital resources and devices in the process of your work?

Ashley: I think it returns to demanding time from the viewer when looking at an artwork, whether it’s to spend more time with the object, observing it, thinking about it etc. As the internet and digital media brings about more excitement, knowledge, and entertainment, I think the quiet becomes more invisible. To make something that can attract and demand attention, whether it’s through shock / controversial value, more visceral, etc. When it comes down to it, to pay attention to something, the viewer themselves must be in a quiet or peaceful mood as well. And I think it’s hard to arrive at that when everyone is living in a very fast paced and usually stressful environment now.

My papercut sculptures themselves require a computer program to do the repetitions and to make precise sizes for the calculations and forms that I need, so that everything closes seamlessly when I create the form. In that sense, without the program and printer, I cannot make my work. But at the same time, because of the details and size, the work itself also cannot be cut by a machine (not on paper, at least). In terms of time, I spend about 2-3 weeks to make a pattern depending on the complexity of the sculpture. Then another 2-3 months to do the paper cut. I work about 5 to 6 hours everyday.

Susie: Thanks, Ashley. It has been very illuminating in understanding your processes and the very personal thoughts that underlie your work. If I may say so, though your art springs from the interiority of your mind, they are reflexive of the world around you, the struggles that you encounter everyday, and distilled into these delicate artworks.

—

This dialogue took place through email exchanges between Susie Wong and Ashley Yeo between 14 and 26 June 2020.

Copyright and Image Credits:

© Susie Wong, Ashley Yeo, Mizuma Gallery.