Read the full artist talk between Zen Teh & Hera here.

___________

Hera: Hi everyone, thank you for your presence here today. We are proud to present a solo exhibition of Zen Teh, titled Mountain Pass: Negotiating Ambivalence. This exhibition actually began with Zen’s residency in Bandung, at Selasar Sunaryo Art Space in Indonesia. Here, you are able to see some photos of Selasar Sunaryo Art Space. It is quite a big space and Zen’s exhibition occupied two gallery spaces.

This previous iteration of Mountain Pass was curated by Chabib Duta Hapsoro who is Selasar Sunaryo’s in-house curator. Pictured here (second from left) is Pak Sunaryo, an eminent Indonesian artist and also the Founder of Selasar Sunaryo Art Space. So, let’s hear more from Zen about her experience.

Opening Reception of Mountain Pass: Negotiating Ambivalence at Selasar Art Space, Bandung, Indonesia (2019).

Zen Teh (Zen): Firstly, I would like to thank the National Arts Council Singapore, who has generously supported the residency and exhibition. And of course, to Mizuma Gallery and Selasar Sunaryo Art Space for helping to make it happen. Lastly, to SOTA (School of the Arts), where I am a full time educator and I am very glad that the school has been supportive of me doing this residency and having the exhibition.

The two months of residency at Selasar was very important for my practice. I found that it was a very enriching experience because holding a full time job actually makes it difficult to have a continuous length of time where I can dive into developing the depths of my practice, especially in a particular project. In this residency, I was able to have that time and space and the physical and mental capacity to go into that depth which I think for a very long time I have been wanting to do so. I have been feeling that sense of bottleneck in my practice for a while until I was able to go on this residency. So for that, I am very, very thankful.

Selasar Sunaryo Art Space was also a space that helped make the residency and exhibition happen because they provided a very conducive space, a very large studio that I was able to work in. As for the support and staff, there was Pak Sunaryo, whom as Hera mentioned is one of the renowned and established Indonesian artists. He is more than 70 years old now, and has a wealth of knowledge and experience in terms of his practice, some of which he was able to share with me. In fact, just to share a little bit about how I even began with this residency in mind – it first happened when I was in Jakarta and chanced upon a book on Wot Batu by Sunaryo, the artist himself. Wot Batu is a stone temple that he created along a hill, on a piece of reclaimed flat land. There, he created a series of stones installations spread across various parts of the journey, leading up to the hub of the whole temple, to talk about his life experiences. You get to sit and interact, contemplating on how you would interpret his life experiences. I found then that the use of stone as a material in his work was very powerful. I was also able to tell the sense of time and history, which really inspired me to find an opportunity to learn from him. That was about 3 years ago, back then I searched through all my contacts for people who stayed in Bandung that I could start having this conversation with. I managed to contact Roy Voragen, a curator who was based in Bandung with whom I began this conversation with, and I eventually pitched for a project. I flew down several times to present my work to Pak Sunaryo himself and the Selasar team. I am thankful that they accepted my proposal and I was able to undertake a residency there.

During the residency, Pak Sunaryo would often give me feedback about my work, which I think really spurred me to create some works which you may find unusual in terms of what I usually do. Take for example a key installation, After Monument: Aquifer of Time (pictured), which has been recreated here (in Mizuma Gallery). As the exhibition space in Selasar is about three times bigger than Mizuma Gallery, there were two other large installations from the first presentation which unfortunately were not able to be exhibited in this space. We will share a little more about them later on.

Hera: As Zen mentioned, she had a great time in Bandung. For sure an artist residency has a lot of benefits and you emerge from it with new artworks produced. However, it is more than that; it has much bearings for the future and as well as the encounters between people and the relationships you form. That is in fact the focus of our talk today, basically things that were resolved into the form of artworks and also things that kept intriguing us, making us think about what else can we do.

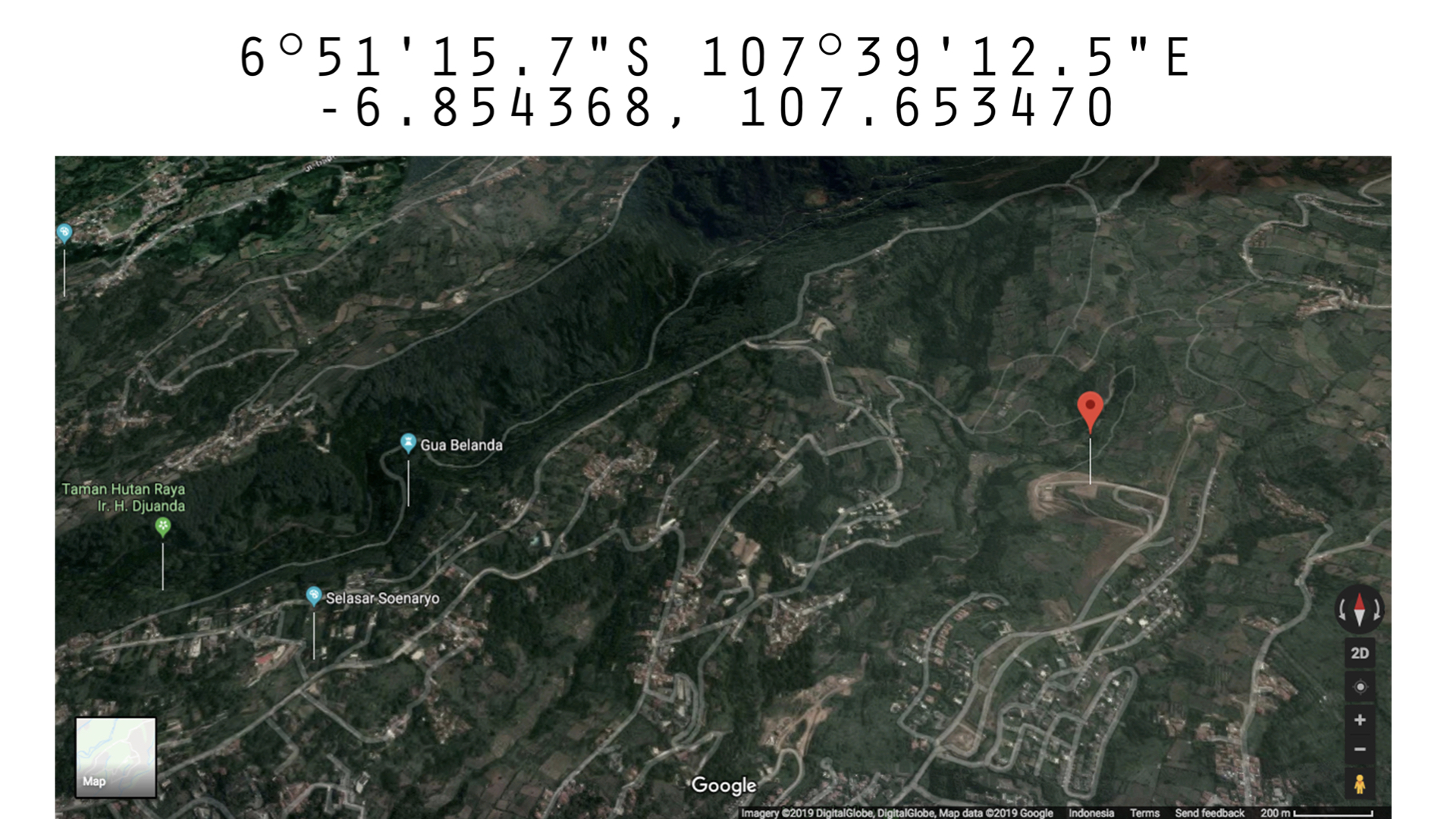

This is Resor Dago Pakar, which is an area within North Bandung. Bandung is a mountainous city in Java, and the lower part (South) of Bandung is quite urban, whereas its Northern part (pictured) is actually still quite green. Bandung, especially the North, thrives a lot on domestic tourism, such as people from Jakarta, a very urban city, who come looking for cooler and fresher air. Lately, what has flourished there is a particular brand of eco-tourism whereby they clear a patch of land and introduce nature-associated activities such as boating, but in an artificial lake, or zip-lining. Another popular attraction is a selfie theme park, spurred by our increasing participation in social media as well as digital photography.

This is Selasar Sunaryo (points at image) and this particular site here is the Resor Dago Pakar, a construction site. It is quite an important site which sets the locus of Zen’s artmaking and interdisciplinary collaboration. So would you like to speak more about how you navigated the whole area?

Zen: So when I first started this residency, I had an idea that I wanted to do something with rocks and stones, but I was not sure exactly what. With a little research prior, I knew that this whole area was a volcanic land. So I wanted to find out the geological history of the site, of the whole area, and that was the starting point. I proposed to work with geologists, initially from UNPAD (Padjadjaran University). But within Selasar’s connections, they managed to find Dr Andri Slamet Subandrio from ITB (Bandung Institute of Technology) who was the first geologist that I spoke to. Speaking with him allowed me to understand the general geological history of the area. Meanwhile, I continued to look for more sources of factual information on Bandung’s history and its urban development. I then met Mas Aji Bimarsono, Director of Bandung Heritage, an NGO that looks into the conservation of the heritage in Bandung. They began with a more colonial, historical aspect, and are developing into other areas as well. He too was very generous in sharing with me about the whole development area, of which I will speak more about later on.

Left to right: Aldiansyah Waluyo (Videographer), I Made Ananta (Artist Assistant), Zen Teh (Artist), and Hera (curator)

It basically all began with the many conversations I had, with the help of I Made Ananta, a Fine Arts graduate of ITB whom I had as a local assistant. He would bring me around on a motorbike, where we travelled the whole vicinity around and close to Selasar, as well as to a few hills. In this picture, Made is the second handsome chap (from the left), and I (third from left) looked very youthful there, and that is Hera (fourth from left). The first guy on the left is our videographer, Aldiansyah Waluyo, who was engaged by Selasar Sunaryo to document our process.

When we were going around, my idea was to have a good understanding of Bandung by surveying the whole area and to find some potential sites to talk about. Besides that, I wanted to talk about a worthy cause; an environmental issue that I want to raise some awareness about. Those initial conversations with Pak Andri and Mas Aji highlighted some environmental issues and I wanted to see how they have surfaced in the land around Selasar. I was also mindful as to not find somewhere too far away because that would not be practical, knowing that I would want to do very intensive research and did not want to go back and forth all the time. It was also rainy season then so after enough experience, we were well-versed on how to protect ourselves from the rain constantly splashing onto our faces while we were on the motorbikes. On our journey, we actually managed to find a waterfall (pictured), which even Made, who grew up and resides in Bandung, did not even know about, so he was able to discover some new things about the land he lives in.

I also made it a point to engage with locals, so with Made’s help I was able to conduct some interviews with the residents of North and South Bandung, which are shown side by side on two screens. We also found the largest construction site in the whole vicinity, and from the conversations we know that this is located at the North of Bandung. The North is actually the green belt of Bandung due to their very lush volcanic soil which acts as the main rain absorbency area. Being on higher grounds, it helps prevent flooding in the lower grounds. From this investigation, we realised that the developments in this area had contributed to the severe flooding in South Bandung.

Pictured here is the top of the construction site, and on the other side is the existing luxury homes built by Resor Dago Pakar. As you can see, this area is the water catchment area, much like a very big well, that taps into the water of the whole area.

One of the things we discovered was that when these big companies come in, they have the resources and technology to tap very deep down into the ground to get the layers of aquifer, the underground layer of water, unlike the residents who can only dig wells, limiting their access to only the top most layer. So what happens is that they (companies) are able to take the water first, leaving water shortages in the North of Bandung and later on selling the water to the residents.

Hera: As Zen has explained and showed to you, she found quite a number of interesting sites around Bandung. For me personally, originally from Jakarta and paying annual visits to Bandung, my experience differed this time as I followed Zen to some of her site visits. I realised then that even Selasar’s staff members and Chabib, the exhibition curator, were keen to tag along, as they were interested to discover more about the area that they live in. This video shows the construction site of Resor Dago Pakar.

Zen: Another interesting discovery I made was when I met a guy named Troy who is a local land owner’s son. He studied in Australia, and we had a wonderful conversation as there was no language barrier. I got to know him when we were on the motorbike going around surveying the area, and I found a lot of debris in just one section, right at the cliff (pictured).

I decided to stop and take a look, wondering what was happening and why there was so much debris. I noticed then that Troy and his father were hanging out there, so I approached them and started a conversation with them. I asked them if they know what this site was and about the debris, and to my surprise he explained that this land belongs to his father, and the reason for the debris was because they were inviting the construction sites from all around the area to deposit their dump onto their land. They further elaborated that this is a very cheap and effective way to reclaim your land, to fill up the land to build flat land. There was a lot of rubbish and they even hired a worker (as seen in the picture) just to go around the cliff picking up plastic rubbish and food waste that cannot be part of this landfill.

Troy also shared with me a little about his backstory and his vision; he was reluctant to leave Australia. But his father lured him back by enticing him with this land and allowing him to develop it into whatever he wants. So he has this vision that in the next few years, he could turn it into a selfie theme park. Selfie theme parks, as Hera previously mentioned, is very popular in the North of Bandung and a little further down as well. As this land is quite steep, he plans to build the theme park in tiers, in terraces with various attractions. His land is also quite strategic as it is located right next to this cafe, a popular haunt for cyclists who cycle from Jakarta to Bandung to go up a very challenging hill. Located uphill is this cafe which is famous for its bandrek, ginger and milk tea.

He was also very generous to introduce me to a farmland close to his area. The farmland has a small cafe with huge sculptures of flamingos, giraffes, and an angel or a Greek goddess. This ad-hoc mix of huge sculptures were placed amidst the alfresco area as a dining experience. These strange encounters were rather interesting. All these conversations about the selfie theme park made me want to find out how does one actually look like. So when my elder sister came to visit me during my residency, we went to Lembang where they had some of these attractions to see what this eco-tourism looks like.

Hera: When I heard these stories from Zen, I was actually quite horrified that the local authorities were not really intervening because the debris were just being thrown down and we were not sure what will happen downstream.

Zen: After the conversations I had with him, it prompted me to ask if he knew of the largest construction site in this area. He pointed us towards Resor Dago Pakar, the same response we received from other locals as well. With this certainty in mind, we went ahead to investigate this site (pictured).

Here (pictured) is Made talking to talking to a construction worker who was at the Dago Pakar Resor site. We also went to visit the houses around that area to find out how their lives have changed as a result of the construction

This volcanic rock (pictured) is included in the exhibition, as part of the rock installation on the wall. The surface of the rock has turned red from the iron, due to the natural weathering process that happened to it. I find that this relates to the metal beams, pillars, and all other structures you see. So these are some of the connections I draw, because regardless of whether it is manmade or natural, interestingly there is an intersection there. So on the surface of it is actually an image of the oil spill from the excavators. I captured this image of the oil spill and imprinted on the surface of the rock that was found and dug out from the construction site.

Hera: There is a particular geological term called ‘outcrop’ which refers to stones that emerge on top of the ground after it has been buried for many years. This happens mostly due to natural forces, for instance earthquakes, being in the fault line, or river erosion. What we have here is a particular outcrop resulted from human intervention – by moving large patches of soil to create flatland in order to build on top of it. I find it very interesting that all the stones in this exhibition were a result of the outcrop from this construction site, with Zen now capturing a particular moment in Bandung’s development.

Zen also collaborated with a geologist, Rinaldi Ikhram from UNPAD (Padjadjaran University). This is Rinaldi alongside Zen at the Resor Dago Pakar construction site.

Zen: I wanted to find out from Rinaldi how can we understand what was here before the construction. We assessed the site together as we picked up some rocks and tried to study what they are. You will see at the back of the gallery a documentation section of some rocks that we picked up and analyzed. The four types of rocks that we picked up are also presented as part of the installation.

From the analysis and the site visits, we found that raw coal was present (pictured). You can also see them in the wall installation of the exhibition, they are the smaller rocks, with a darker shade of brown and are very brittle. They are the coals that are used for fossil fuel burning, but these ones here are thousands of years too early to actually be used. Even though they are about a thousand years old, they are still considered to be at a very early stage.

Site Research: Zen Teh (Artist) with Rinaldi Ikhram (Geologist) at the Dago Pakar Resor construction site

One of the things that was fascinating to me was the understanding of time. As human beings, our lifespans are only so short and our conversations could be only limited to for example, what are going to do next week or what we will be having for dinner later etc. However with geologists, they could be talking about things in the context of hundreds, thousands, and even millions of years ago. When these conversations come about, that sense of time, our understanding and appreciation of how we are in context to the universe becomes something that I started to think about as well.

During the site visits, we found raw coals as well as other clay sediments. Judging from the patterns which have been deposited, we were able to conclude very roughly that about a thousand years ago this area was an ancient marsh. The coal were deposits of all the vegetation; due to the latter’s over time compression and eventual deposit as coal.

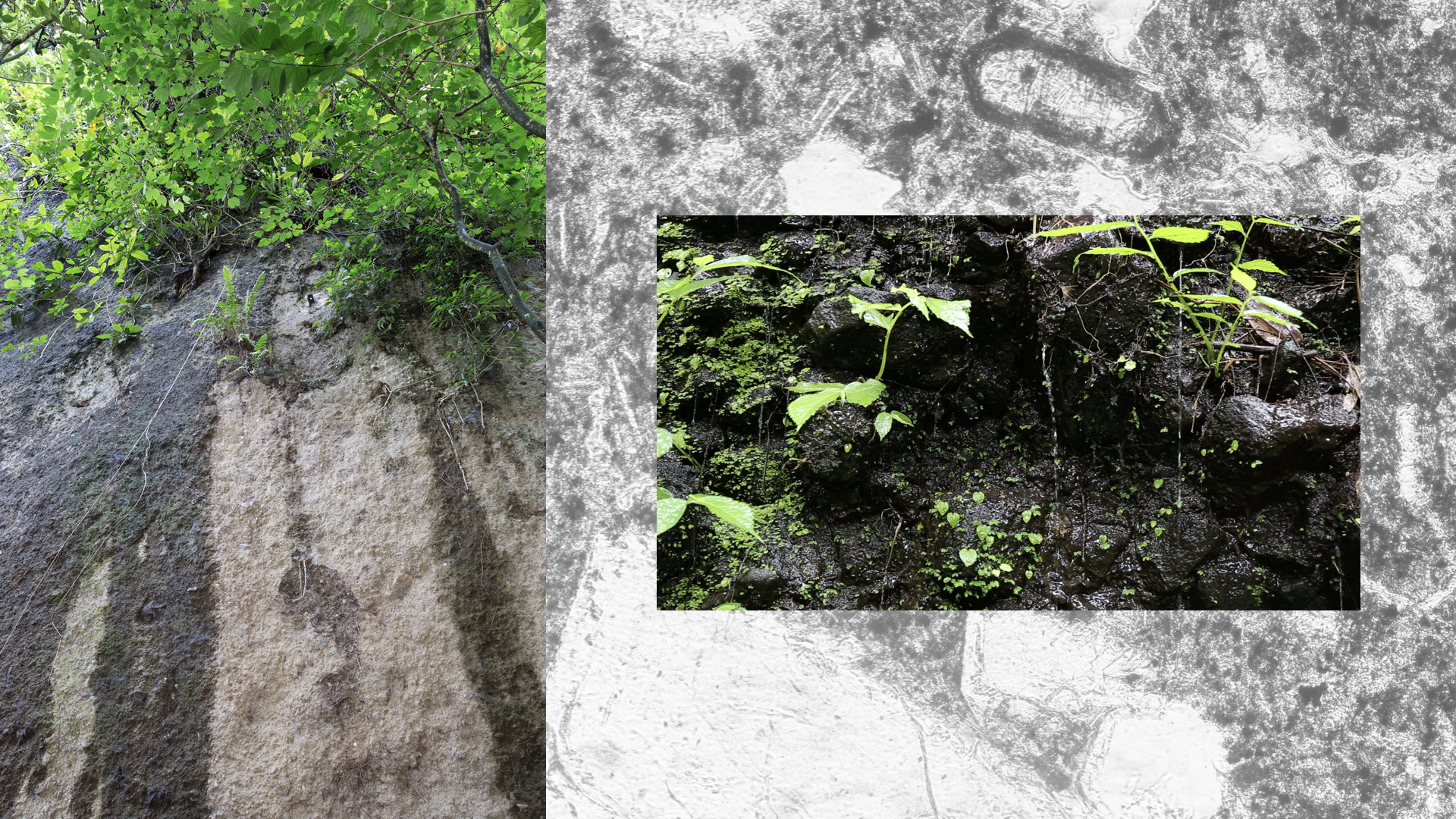

The result of understanding what this place used to be before, in the context of time, is shown as images imprinted onto those found outcrops. The work After Monument: Imprinting Geological Traces 3 (pictured) is an andesite rock, and on the surface of it are images of a marsh I found in Lembang, an area in the same vicinity as the investigated site. On the imprinted image, I wanted to depict what this site could have been in the past. For me, the interesting juxtaposition here is the image of the marsh in Lembang and the found stone – the marsh that used to exist in this site, whereas the stone, containing at least a thousand years of history, was picked up from the ground due to human intervention of digging into the land. So there are many moments in which this sense of time intersects within the work itself.

Similarly, in the work After Monument: Stasis (picture), the stone is placed on a metal disc, presented as part of the rock installation. The stone is placed right at the edge of the disc, any inch further, the stone will lose its balance and fall right over. I wanted to talk about that sense of balance between the constructions and natural elements.

To understand about outcrops and how they naturally looked as a large piece of rock, we had to visit the only conserved forest area called Tahura (Taman Hutan Raya, pictured) located in the north of Bandung, close to both Selasar and investigated construction site. In Tahura, we were able to observe the rocks that were conserved in that area and how they looked in their natural environment. That visit was also joined by Rinaldi, who was able to point out to us what these rocks were, the key functions of having these volcanic materials, and why then is Bandung the greenbelt of the city.

Hera: Rinaldi recommended the visit to this area because it was near a fault line and a river, meaning that there were more spectacular and overt outcrops, and you are able to see the different layers. That was how they came up with the conclusion that the investigated site was once a marsh; from studying its different layers of strata downwards and talking about the narrative from the past.

Zen: Coincidentally when we were there it was the rainy season, so it was easy for us to catch a rainy day. As expected, it rained on the day we visited Tahura with Rinaldi, and we saw the water streaming out of from these rocks (pictured). The water was not flowing downwards over the rock surface, but instead exiting out of the rocks. This was something I had not witnessed before, as I live here in Singapore, so I wanted to understand what this was all about. Rinaldi explained that this was what they call the aquifer effect, a term to describe the ability of volcanic materials to transport water, or also to absorb water downwards. When rain falls, these volcanic materials are able to absorb the rainwater, allowing water to pass through them, and eventually depositing the water into this layer of aquifer, or simply known as the underground water. There are different layers of aquifer at different depths, the natural process is usually a layer of water followed by the rocks, then a layer of water again and so on and so forth.

Earlier on when I shared about the issue of how water tanks (of large corporations) were able to tap water deeper down than locals could, their drawing of water from below cause the water from the top to be sucked out as well, resulting in lesser water nearer the surface for the locals to tap from. From the quality of the aquifer and the ability of the volcanic materials to perform its function, we also discovered that when you construct beyond the recommended amount of 40%, the non-porous concrete will have water running off its surface, flowing downhill towards the lower grounds, and contributing to the flooding in the south of Bandung.

Hera: As we move towards speaking about the installation work After Monument: Aquifer of Time, I would like to begin by showing this picture here of Rinaldi pointing towards a breccia wall (pictured). Breccia is a particular material that is a combination of fine and coarse particles. Though it can be quite brittle, but it is still strong enough to create caves. When the Japanese and the Dutch came during the war, they each had their own caves on either side, using it as weapon storage and bunkers. Rinaldi was using this rock as an example of how it could transport water by virtue of it being porous. This leads to the creation of the installation work and I will now hand it over to Zen to speak more about it.

Zen: Sure, this artwork is titled After Monument: Aquifer of Time (pictured), and the main structure of it is a 2.7 meters tall beam, a second-hand H-beam which was used for construction infrastructure. I made it a point to get this particular H-beam so I could use it as a representation of the infrastructure that I have seen.

Earlier, when I mentioned about the redness on the surface of the rock that was caused by iron, here it also corresponds to the iron content on the surface of the H-beam. So I purchased this from a second-hand metal market and I juxtaposed it with the volcanic soil that runs downstream from the corner of this gallery space. With a spotlight shining on it, a shadow larger than the size of the beam is cast onto the wall behind it, creating this imposing presence and sense of violence. This idea concurrently speaks about the aquifer effect, presented in the video work that intentionally faces the H-beam and soil structure, showing this sort of tense dialogue between the construction infrastructure of the H-beam and the naturally occurring aquifer effect of the volcanic materials.

For the image imprinted on the beam (pictured), the ink is placed directly onto the surface. The image depicts water marks left on the Dutch and Japanese caves, further articulating the sense of time passing and the aquifer effect. Yet, these caves were used in human construction then, sitting between nature and construction.

Here you can see what happened when we purchased it and the welding process of the two metal pieces. It took quite a few men to carry that process out and the most fascinating things to me is that they have to smoke a cigarette when they do anything. You can always see the cigarette hanging from the side of their mouths.

Hera: It is actually a very good welding.

Zen: Yes, it is very strong.

Hera: As you can see in the wall installation, Zen picked up quite a few rocks from Resor Dago Pakar and turned them into artworks. There were also some taken as samples for analysis, and some of the sample slides are presented at the back of the gallery. The geological museum also acts as the center of study where students and even companies could get their stone samples cut into slide samples.

Zen: According to Rinaldi, they are one of the most skillful people in the city, hence explains why many people approach them to get their samples cut.

This rock (pictured) is currently displayed as part of the rock installation, with the label intentionally left on it. They first cut a piece thin strip from the rock, and to get an even thinner slice, they have to sand it down (pictured).

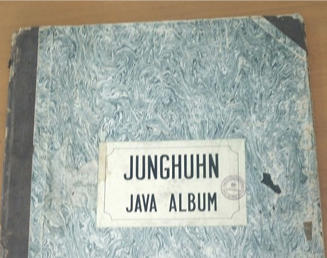

Hera: This is Pak Anton (pictured) and we were in the library of the geological museum. Their museum has a really good library with books dating back to the early 1800s. We have here the Junghuhn Java Album (pictured), Junghuhn is a German geologist and scientist who came to Bandung in the early 1800s, and he refused to leave Indonesia, thus later passing on in Lembang. During his time in Indonesia, he went around Java documenting mountains and partly because of his deep interest in them, he also created lithographies of all of the mountains (pictured).

It was in the museum that we could look at the beginning of a geological survey of Indonesia, as there were previously no other documentation of the mountains. However, this is not considered geological as it did not have a systematic record, such as the materials present. Even when they had learned about the mountains and started to record them, it quickly led to the exploitation of the mountains. Pak Anton was explaining about a particular mountain called Gunung Gamping (pictured), which is a limestone mountain range. Limestone as a material has many uses, such as cooling down metal, making of granulated sugar, and also used for buildings.

Zen: This was still at an early stage of my research. I had told Pak Anton that I wanted to do something with rocks and stones. At that point, I was unsure about venturing into the construction or even the mining sites. He had this book with records of the mining sites from the past ten years or so, which he was quite excited to share with me. This made me realise that if I were to find some of these mining sites, I would be quite far from the vicinity of Selasar and it was not the process that I wanted. I wanted to find a site that was familiar to the viewers; a construction site is something viewers will be able to understand, recognise and relate to in comparison to mining sites. I was not aiming to do something like National Geographic’s linear narrative of mining, and so I wanted to pick a site that is more relatable to everyday people.

Hera: Pak Anton and the other geologists also introduced a lot of different sites in Indonesia that has a more overt examples, something like Gunung Gamping, where it experiences very quick changes to the land. Somewhere there could be a limestone mountain and right next to it is a satellite city built with the materials taken from the mountain. This is currently still happening and I think what is really interesting is this issue of land stewardship; who really owns the mountains, how is geological history important to us, and can we rely on the state to protect the interests of the people and the environment.

This leads us to this particular artwork, After Monument: Mountain Pass, an important work that unfortunately was not able to be brought here as it was made out of soil and organic matter, materials forbidden by customs. Would you like to talk about it, Zen?

Zen: After all the investigations into the issues with the land, we went to find out about the legislation, about the building coverage areas that is allowed by the West Java government. We were told that initially that was twenty percent, meaning if you have a piece of land, only twenty percent can be buildings and the rest of the land must be uncovered to allow the water absorption into the land. As lands develop further, they thought maybe twenty percent may not be that realistic, perhaps we could change it to forty percent. Although the new legislation states forty percent, in actual fact, the building coverage area is more than the stated forty percent. We also looked through the legislation, which we have a thick copy of 82 pages if you would like to have a read, however it is in Bahasa Indonesia. More importantly, we have a summary of it on the shelf, after you see all the images of the site and what I found.

Basically, the whole of North Bandung is broken down into five zones, namely B1 to B5. Each zone has different building coverage percentages according to how much water they could absorb and how close is its location to a densely built areas. If you were to buy a land that is more than the minimum land size, a different legislation or regulation will apply to you. What happened in the case of Dago Pakar is that they had purchased a huge amount of land, and sold it to many different people. So these people own a land smaller than the minimum land size, thus the legislation does not apply to them and they are able to build more. If you were to put them all together, the building coverage area is obviously huge and it is hard for the government to check and accurately calculate the percentage of buildings in the whole area.

Hearing and understanding all of these, there are a lot of grey areas which allow for land exploitation. So this work, After Monument: Mountain Pass talks about that, the aquifer effect, and the violence I have witnessed at the construction sites. I wanted to bring that violence into the gallery, much like After Monument: Aquifer of Time, but After Monument: Mountain Pass is a lot bigger. After Monument: Mountain Pass took about six big trucks of soil. We piled it up to resemble a mountain form in reference to the mountain city, and I made use of the existing panel of wall that was in Selasar’s space, using that panel as a symbol of the construction and intervention into the land, cutting through the soil on both sides.

Viewer standing in the center void of After Monument: Mountain Pass, during the opening of Mountain Pass: Negotiating Ambivalence at Selasar Sunaryo Art Space, Bandung, Indonesia

On each of the sections of soil, I carved and sculpted excavator marks. There was also a huge void in the center, an area that has been carved out and presented to show a very sharp angular mark that has been carved and purposely removed. Viewers are able to stand right in this center void to look at the work, where you can see a trail of gold leaves flowing in a fluid manner downwards almost to the end of the installation. However, it does not reach the end of the installation to show its depletion, and this idea of how the way the land is being treated is not sustainable. You may be able to reap a lot of profits from the start, but the consequence is, along the way you will start to run dry.

Hera: Maybe we could talk more about where the soil came from?

Zen: The soil, in order to be very site-specific to address the current issue, came right from Resor Dago Pakar. To make this a formal request, we sent a letter to them requesting for the soil. We wrote that we are making an artwork and as they are the huge contributors to the development of Bandung, we would like to get the soil in a form of a donation from them. They responded with ‘Oh, you are making an artistic piece of work! Great! We will be happy to give the soil to you.’ They did not ask what it was used for even though the installation was made to critique them. But they were happy to provide the soil to us for free and we only had to pay for the manpower to transport them. If you were to go on to my Instagram, you would be able to view a video of us plowing away in order to loosen the soil to create this whole installation.

Hera: Moving along, this is another installation that did not manage to come to Singapore.

Zen: This installation is called After Monument: Microcosm. Apart from all these issues with the land, I was also very appreciative that I was in a mountainous city. I thoroughly enjoyed the landscape and the view. I started to appreciate the sense of scale, and from the conversations with the geologist, the sense of time, talking about thousands of years, and when I see rocks and landscapes that are so much larger than myself, I think that I was quite overwhelmed by that. I wanted to express that in various ways in which I could interpret the mountain forms.

Pictured here is a found rock from the construction site. When I first saw it, I imagined it as a mountain and led me to add a white patch on the top of it to imitate a mountain.

In this image, I was sculpting a few tonnes of andesite pebbles, also made of volcanic materials. When purchasing and putting together the work, I made sure that they were all related to this investigation. I was trying to sculpt the forms of the mountains and its ranges. In the installation After Monument: Microcosm, you see a whole stretch of sculpted pebbles that interprets the landscape of a mountain range. In the same sense of interpreting mountain ranges, time, and space, there is a video in the background of the installation depicting the currently active volcano Tangkuban Perahu and its crater in the middle (of the video), with clouds passing through.

Another is in the form of a long scroll that is 2.7 meters in length. The image on the scroll is a composite of images of mountains at Kawah Putih, which is in the vicinity of Lembang. I also found the huge rocks in the construction site that I imagine as mountains. Juxtaposing two different sizes of these rocks in the installation creates this sense of scale that is within that island (of the installation). The rocks, which were also outcrops from the construction site, were intentionally selected due to their natural weathering effect rain exposure (pictured). So I have put together all the various interpretations and responses to the mountains in this installation. Even though we managed to bring back this installation, there was unfortunately no space to present it here in this exhibition. Hopefully we will have a chance to show it some time in the future.

Here is a close up of the scroll. (picture)

Hera: On the scroll you are also able to see images of human beings traveling in the fog.

As we come closer to the end of the talk, would you like to share about your future plans and what you have learnt through the residency?

Zen: I hope that I will be able to journey more into the landscapes and be able to learn more. I see the whole point of doing all the work that I do as a learning journey. This has been a very meaningful investigation and the whole project be it in Bandung or for the series of Garden State Palimpsest in Singapore, and much earlier in 2013 I did a residency in Chiang Rai, Thailand, a rapidly developing mountainous city. So this whole line of thought was all to investigate the Anthropocene, when we humans are able to make such a significant impact to the land. My plan is to be able to go into various rapidly developing cities in Southeast Asia in order to uncover more of these stories.

Hera: Thank you very much and we have come to the end of our talk. Before we end, does anyone in the audience have any questions?

Audience 1: Could you talk a little bit about the metal pieces on the rocks? Why and how did you incorporate the metal into rocks?

Zen: They are used in many different ways. The one that I have mentioned, After Monument: Stasis, is balancing on the edge of the metal plate. There are a number of pieces that are balancing with the metal pieces, some are on the shelves in the rock installation. After looking into so many environmental issues in various places, the biggest question to me is how can we strike a balance between progression and development with nature conservation. I recently read an article in the Guardian that talks about the possibility of us planting one trillion trees, and if so, it will be able to take out two-thirds of the carbon emissions in the ozone layer. I feel that it is possible if we could find a way between nations to collaborate together. So it is the idea of striking a balance that is being investigated in these few pieces. Also, when I am balancing them I am mindful of the similarities between the iron and the weathering red surface, and a lot of it is based on what they represent and how they look together visually.

As for the other works which are slicing or cutting through the rocks, those are part of a series called Intrusion. They are the representations of violence that I had repeatedly seen throughout the two-month residency as more and more constructions were being done. I witness that all the time, and it is something I really want to show through many of my works. The metal piece that cuts through After Monument: Intrusion 1 was found in a second-hand metal market where I specifically looked for metal pieces that could evoke that sense of violence. I knew that for this piece in particular, I wanted it to look like an axe cutting through the stone. The metal needs to be in this particular position, not any lower or higher, as it has to look as if it is in the process of being cut through. After Monument: Intrusion 2 has a metal rod piercing through it, interestingly has an image imprinted on the metal rod itself. It is an image of the greenery in Tahura, which is the remaining conserved area of the forest.

Any other questions?

Audience 2: My question is sort of related to this actually. When I saw the slicing and piercing, I thought what you were going for was the sort of antagonism of violence. But when I saw the piece that you just mentioned [After Monument: Intrusion 2] with the metal rod which looked like it sort of crumbles a bit, like you have mentioned with the rust on the surface. I wanted to know if there is a sort of cyclicality that you are after. Do you sense more of this idea as a violence or conflict, or do you see it more as cycle, that the materials will go back to the earth, and so on?

Zen: I suppose both. I think at the moment what I encountered was mostly violence. I always hope that we can find a balance and that we can see the similarity between man-made or man and the natural. When you mentioned it being a cycle, most definitely, we are all going to return back to earth whether we want it or not. So that is something we could live with and sort of live harmoniously together, which I hope I am able to see in my lifetime.

Hera: Thank you all for coming and we would love to catch up more with you during the opening reception. If you have any other questions, we will still be here. Thank you very much.

—

Copyright and Image Credits:

© Zen Teh. All images courtesy of the artist, Selasar Sunaryo Art Space and Mizuma Gallery

Transcribed by Cai Yun Teo, Marsha Tan, and Theresia Irma.