“Some people believe these stories you tell them, even if they only look at the pictures, they believe Rihanna was raised in Indonesia, and some others don’t. Do you think this makes people more vulnerable to hoaxes or to conspiracy theories as well? That people really believe what they see in the pictures?”

– Anna-Catharina Gebbers

This weekend onwards, we will be posting a special segment of Mizuma Conversations, featuring artists in conversation with curators.

Tune in to our very first session of Artist Dialogues: Anna-Catharina Gebbers, curator of Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin in conversation with Indonesian artist Agan Harahap.

Anna-Catharina Gebbers is a curator of the Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, where she is responsible for international media and performance art. An essential part of her curatorial practice are international collaborative projects like the exhibition chapter Making Paradise. Places of Longing from Paul Gauguin to Tita Salina (in collaboration with Grace Samboh and Enin Supriyanto) for Hello World. Revising a Collection (2018), as well as the research and exhibition project Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories (curated with Gridthiya Gaweewong, Grace Samboh, and June Yap, MAIIAM/Chiang Mai, Galeri Nasional Indonesia/Jakarta, National Gallery Singapore, and Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, 2017-2022). As a freelance curator she has recently developed Deep Sounding – Histories as Multiple Narratives (curated with Melanie Roumiguière, daadgalerie, Berlin, 2019). Gebbers also runs the interdisciplinary project space Bibliothekswohnung in Berlin and is an editor at polar – Politik, Theorie, Alltag.

Agan Harahap graduated from STDI Design and Art College in Bandung, Indonesia, where he majored in Graphic Design. After which, he moved to Jakarta and photographed for Indonesian-based music magazine, Trax Magazine. He held his first solo exhibition in 2009 and has since been exhibited in various photography shows around the globe. Harahap’s photographs depict his subjects in surreal situations that mislead the realism of his work and question our reliance on photography to inform us of reality.

Scroll through to watch a video excerpt of this dialogue. A full audio recording of this dialogue is available on our podcast, and as a text transcript below.

Watch the Video:

Tune in to the Podcast:

| |

| |

___________

Anna-Catharina Gebbers (Catharina): Hi Agan!

Agan Harahap (Agan): Hi Catharina!

Catharina: How are you today?

Agan: I’m good, just finished fishing – eh, swimming with my children. Catharina: Wow. Where did you go? To a pool, nearby?

Agan: Yes, nearby. There is a hotel and there is a swimming pool, and it’s discounted, because of this Covid, there is no visitor in that hotel. Very cheap.

Catharina: Wow. So, because of the pandemic, I can imagine. I’ve heard that there are 3,000 artists living in Jogja, which I think is quite a lot for a city with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, so it’s a high ratio of artists.

Agan: Yes, but like you know we are in the same neighbourhood, most of all it’s the same region. Yeah, next to my studio is my friend’s studio, 100 meters is another friend’s studio, so we’re in the same area, same district. But because of this pandemic, we cannot see [each other as] often as usual.

Catharina: When did you move to Jogja? You were born in Jakarta, right?

Agan: Yup, I was born in Jakarta and I moved to Jogja on 1st of January 2014. Yeah, I moved to Jogja in the New Year.

Catharina: And for what reason? Why?

Agan: Because it’s more reasonable to live here as an artist. When I was in Jakarta, it didn’t make sense, because I had to spend a lot of money just to pay all the bills. In here [Jogja], it’s cheaper and it’s very reasonable for artists like me.

Catharina: Can you explain a little about how your artistic work developed? Can you say how it all started? So when and how, for example accentuating the artificiality of photography, which were the first series you were working on. For us, at Nationalgalerie [Berlin] we are very happy that we now have Mardijker Photo Studio in our collection, but there were more series of works before, like Our Memory Album, which is a series from 2015-2018. So maybe you can explain a little bit which were your first works and how they’ve developed.

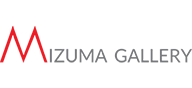

Agan: Okay, my first artwork was called Octopus’s Garden from 2008 I guess, or 2009. There was an open submission in the National Gallery [of Indonesia] in Jakarta at that time, so I just submitted it and was nominated. So that’s the first time I exhibited at the National Gallery in Jakarta. After that, I started to know other artists, because of the exhibition, I had more confidence, because before that I was just –if there’s an opening at the National Gallery, there must be free food and free beer [laughs], so I had to go there. And I never talked to anybody, I knew this [person] was an artist, that [person] was an artist, but I never talked.

But since I was nominated and I had the exhibition at the National Gallery, I had more confidence to talk with other artists. So I met Angki [Purbandono] from MES 56, and we talked a lot about photography, especially in digital photography. And in 2009, he invited me to have my solo exhibition in MES 56. After that, I had a sense of what is good and what is not good, you know what I mean? I can make artwork based on what I see from the timeline on Facebook, I see what happened, I read about politics; so I can make something, I can make artwork. And it has continued up till today, there’s Mardijker Photo Studio, yeah, it’s part of it.

Catharina: Mm-hmm, and how many online projects do you have? For example, you’re posting on your blog “Melman and the Hippo”, and you have the Instagram account @sejarah_x, and also you can tell us how you are involved in @pingpongaffair_?

Agan: At first, I was using Multiply. But since Multiply closed, I moved to Blogspot. And then Twitter started, Facebook, and recently Instagram. Actually for @pingpongaffair_, it’s my wife’s account, her business account where she can sell her products. Next, @sejarah_x is another part of my artwork, it’s about a combination of true and fake history, so it’s very hard to tell whether it is real or not. And then I manage @mustaqim_tailor, it’s my merchandise, and of course lastly there’s @aganharahap, it’s my account. So how many, around 4 or 5? [laughs]But I don’t use it every day; for example for @sejarah_x, if I have an idea, “Oh okay, this is interesting to post”, then I’ll post. I don’t maintain it daily.

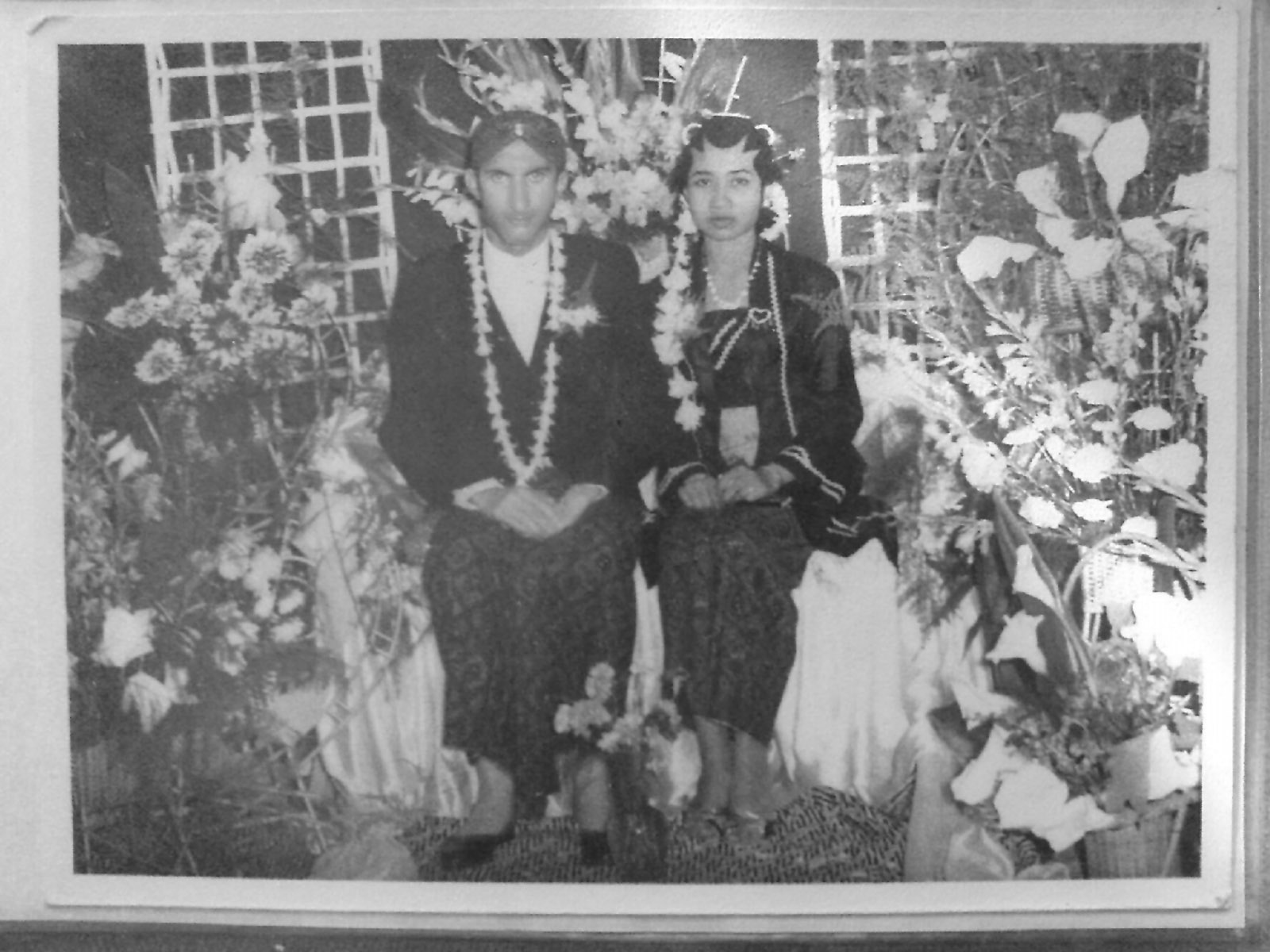

Catharina: And for example, for your Our Memory Album series, you also take – you use people’s social media accounts as a resource. So you are sourcing, for example, the family snaps from other accounts, and by this you are showing also to the users what can happen if they don’t resize their images, or if they don’t set their accounts on private settings. Correct?

Agan: The funny thing is that I have a series of photographs, the title is And Justice For All, which is a title of a song from Metallica. So it’s celebrities who got caught by Indonesian police, so where can I get the images of police? You know, Indonesian police have Blogspot or WordPress – minimum is a Blogspot. I don’t know, they never resize the photos. It’s very weird, you can print it up to 1 metre. And I get them from the official police. There are many police offices in here, random police offices in Jogja, so I can get very big, good quality [images] for my editing. Even the police – they don’t realise they have to resize, or they have to at least put a watermark. So okay, I pay tax, so I think I can use it.

Catharina: Your interventions are, let’s say, rather unexpected. People don’t – they’re really surprised by this. I think these are inventions in popular, but also in archival imagery, like the archives of ethnological museums. And so you use these strategies which we call ‘appropriation’ and ‘digital manipulation’, allegory and, I always love the way, how you also use irony. So along with the photographs, for example in the series Our Memory Album, you also appropriate or make up personal stories attached to them in order to give them a truthful context. I always – I mean I use Instagram’s translation tool, so I translate them and I read them and they’re so dense, and so poetic, I really really love them.

But also, in this celebrity series, you use for example, photos of Rihanna or Brad Pitt or somebody, and so you kind of “Indonesianate” them. I would say, the stories you tell are also as important as the pictures, and they tell – they talk about what a good storyteller you are, you’re a really brilliant storyteller. And I think this is another way of how you’re telling your viewers or recipients that pictures also always tell stories, there is always a layer of made up truth or reality which, – and I think this goes even deeper if they realise that there is an algorithm behind what comes into their feed of their stories. Would you say this is correct, that this is another storyteller – the algorithm, maybe?

Agan: Yeah talking about algorithms, yeah, maybe. But to me, the situation has changed in Indonesia. Now there’s a law that – there’s a law on how to use social media correctly. The caption, the story, for me it’s like, for my safety also. Because, before there was this new law, people can take my photo on Instagram and they can spread it and they can use it for their political purpose, or for everything.

I have an example, I edited – when the Arab King, King Salman from Arab came to Indonesia and I edited him with one of the religious leaders from here [Indonesia]. And then they captured it and they spread it, and told people that this is true – King Salman was meeting with our leader. But it’s not true.

King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, King of Saudi Arabia pictured with Habib Muhammad Rizieq bin Shihab, leader of The Islamic Defenders Front.

So for me nowadays, the caption is for my safety. Because people cannot use [the image], people have to read [the caption] and they realise “Okay, this is not real, this is not real, it’s impossible.”, because they read my caption. But mostly, they never read the full caption. They just capture and they spread. It’s still a problem for me and I’m still finding a way to solve that problem.

Catharina: So I think this also brings in another layer, because some people believe these stories you tell them, even if they only look at the pictures, they believe Rihanna was raised in Indonesia, and some others don’t. Do you think this makes people more vulnerable to hoaxes or to conspiracy theories as well? That people really believe what they see in the pictures?

Agan: It depends. But for most people, Indonesian people, if they see that the source is Agan Harahap, they don’t – they start to not believe it. They never believe it. Because I usually edit the photo, so even when I post [pictures of] my children, and my followers would say “Okay, this photoshop is not good, the lighting is not the same.” But I just took my children’s photo from my phone and just posted it, and people always comment about the editing technique. And it’s like, okay. [laughs]

But for conspiracy, it becomes more complex, if you want to talk about this pandemic era. So many news that we, at some point, I’m choosing like – not to believe everything. Believe what you want, believe what I want; what I wanna believe, I will believe it. But that’s the only option for me right now, I cannot – with the news. And if I just start to believe, no. But at this time, I think I have to calm down first and then be more attached with my family, don’t get involved with the news, with what’s happened recently.

Catharina: So Agan, I remember – Agan when you were in Berlin and you met Mike Tyson and you posted the photo and everybody said “Oh wow, this is photoshopped!”. You remember? When you came to Berlin and met Mike Tyson?

Agan: Oh, yeah, yeah. They said, “No way. You’re taller than Mike Tyson? No, it’s impossible!” What, yeah. But that’s my risk. [laughs]

Catharina: How many of the celebrities whose pictures you’ve used are commenting on your posts? I know that at least, Jokowi answered your hoax with a fun post – this was really great.

Agan: You know like, yesterday – I didn’t edit a photo, I painted one celebrity, a porn actress from Japan. I painted her and she commented, and reposted it. And like okay, wow! [laughs] She’s a porn star, but the other celebrities never commented a lot about it. Because every day, in an hour, many people would tag the photos of them, so it’s very hard to get attention from them. Yeah, just yesterday, I had a comment and repost from a Japanese porn actress. [laughs]

Catharina: In addition to the projects based on family snaps, as mentioned, you also use photographs from the ethnological collections from online portals of museums. You have posted some of your “revisions” of these photographs on @sejarah_x. Can you please talk a little bit about how this work series differs from the Our Memory Album? Is there also a difference in regard to which layer of truth you are addressing. I mean, which reality you are addressing.

Agan: It’s different, I have two accounts, @aganharahap and @sejarah_x. Most people never know that it’s me behind the @sejarah_x account. If I have to edit Our Memory Album, it’s more like a joke, you can see all the celebrities. But in @sejarah_x, it’s different. So people, most followers of @sejarah_x are youngsters, very young, and they are really happy if they think they know something, “Oh our history!” – so I play with that narration. It depends on me, what narration I want to drive.

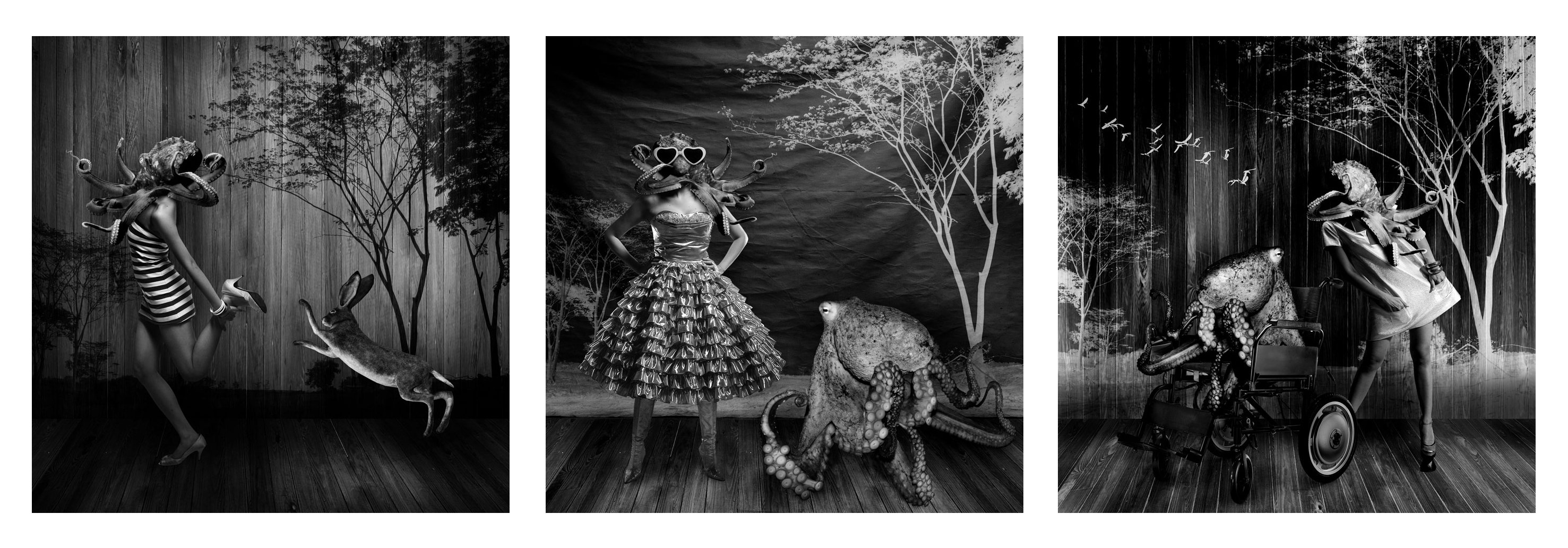

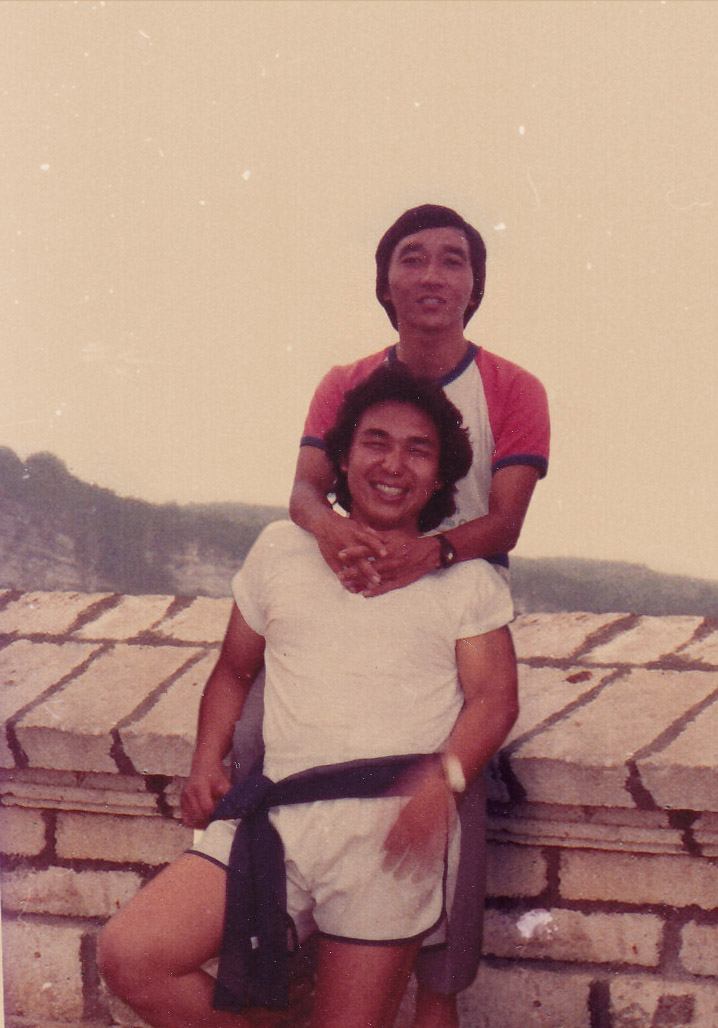

For example, for the Jogja Biennale, I made some of the family portraits series [Dear Sara (2014)], but the narration was about marriage of different religions, different cultures, and mixed weddings. There’s also [a narration] about a gay uncle who falls in love with another man, stuff like that, and people commented “Oh, so this is from long time [ago]”. So I can play that narration, but with no joke. Because at that time, people never published their private photos. So I made the photo, I made the narration, and people believed. And I think, yeah, I think it’s good.

Catharina: Are you also interested in the history of photography in Indonesia and Southeast Asia in general, and the medium of photography as a specific tool as an artistic device?

Agan: Yes, as artistic yes, but for me, I’m more interested in the smartphone era, photography and smartphone era, because it’s the new technology, people still adapt to use it. Even my mother; she just learned this week how to send a photo from her new smartphone. Yeah, and that’s my mother. So many people like, I don’t know where in Indonesia, they think what they see on their smartphone is real, but it’s actually not. People just start to believe “Oh, this is real, this is not true”, stuff like that. Of course I have concerns about photography history since colonial era in Indonesia, but my concentration is more on the digital and smartphone era, and social media.

Catharina: When you use Photoshop, is it for you like a painting tool? You do a composition of the picture?

Agan: Yeah, of course. But in Photoshop, it’s not like a painting, it’s like composing. How to create photos realistically, so people won’t think “Oh it’s edited”. It’s a different composition from painting, we have to take – like if you take a snapshot, it’s different when you do staged photography, right? So it’s quite hard to do things like depth of field, lighting, and the technique is quite difficult. But that’s the challenge.

Catharina: Since spreading images and stories online: What made you decide to print out some of your images? What is the difference between using social media as an artistic medium or using photographic prints as an artistic medium? At Nationalgalerie, we bought prints.

Agan: So okay, it depends. If I want to make artwork to show at a gallery or for people to collect, of course I have to print. Because I’m still thinking about how to make my online artwork become offline. That’s my other challenge. But it depends. Not all my artwork can be printed but yeah, sometimes I put it just online. It’s more powerful if some of my artwork stays online, not to be printed.

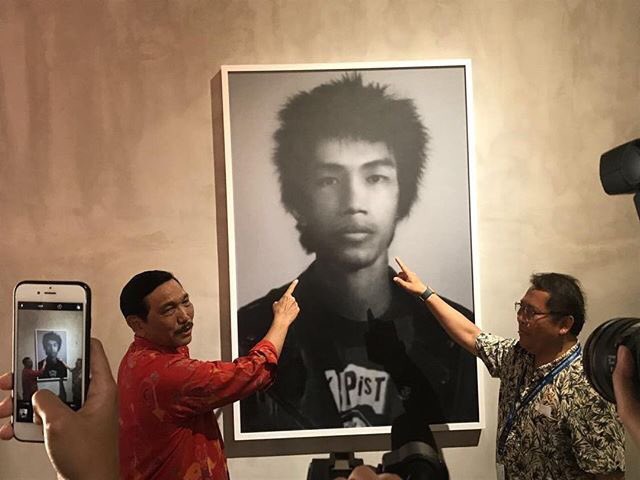

But yeah, even like for example, the Jokowi image [I Was a Punk Before You (2018)], it’s powerful online but in Art Bali two years ago, we had to print the Jokowi because all ministers were coming to see the exhibition! [laughs]. So they are equally as powerful. So yeah, I have to decide which ones to print, which ones stay online, which ones can take both, yeah, stuff like that.

Exhibition view of I Was a Punk Before You by Agan Harahap at Art Bali, 2018. Posed in front of the artwork are, L: General (Ret.) Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs of Indonesia; R: Rudiantara, former Minister of Communication and Information Technology of Indonesia.

Still image from video interview between Agan Harahap and Anna-Catharina Gebbers on Skype, 13 June 2020.

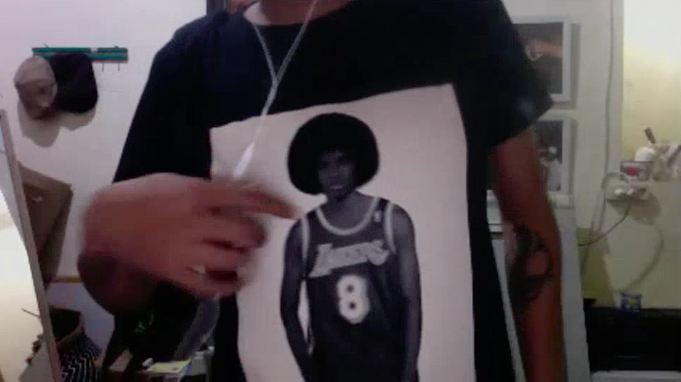

Catharina: And you have it on the T-shirt as well?

Agan: Yeah, the T-shirt of course.

Catharina: Are you wearing a Jokowi T-shirt as well?

Agan: Oh no, no. It’s Michael Jackson and Kobe Bryant. [stands up to show T-shirt]

Catharina: The interesting thing about the Jokowi print at Art Bali was of course that people used it as a selfie spot, and it re-entered social media – so it was a perfect circle, it was really great.

I miss the stories behind the photos, [the stories] you tell when you post the photos. But I think you have a very interesting way of doing a wall layout with the prints and you have specific decisions on which frames you are using. Maybe you can talk a little bit more about this arrangement of – for example Mardijker Photo Studio, I saw it in different variations, I saw it in Singapore, and you made a specific wall layout for Berlin, for example.

Exhibition view of Mardijker Photo Studio by Agan Harahap at the “Singapore Biennale 2016: An Atlas of Mirrors” at Singapore Art Museum, Singapore, 2016.

Agan: We cannot say only for Mardijker, but some of my artworks can be framed, some are better not to be framed. Like Jokowi [I Was a Punk Before You] in Art Bali, it’s not in a frame. But for Mardijker, I got inspired by the photo industry in Indonesia. I have some giga of archives and I saw the studio in that era, the photo studio in that era, they printed a whole wall full of photos. That’s what I’m thinking. In the Noorderlicht Photo Festival, I made gold frames. But for Berlin, it’s cool to be very simple, minimalist, with wood. But because in Berlin, the colour of the wall is white, so it’s perfect. If I put a gold frame or shiny frame, it’s not good. But in Singapore, the wall is red, I can talk with the curator ‘I want the wall colour to be red’, so yeah it’s about technical aesthetics. It’s different, I can make another layout actually.

Catharina: I think this is interesting, this shift from the online space to the actual space and that you really use the actual space and you can see this, if I for example do research on how you composed Mardijker Photo Studio, really in different ways, and it also tells different stories. For example, if you use the golden or the ornamental frames, it has something a little bit more of a family wall, or in a more academic style hanging. In Berlin, it was really almost like in an ethnological museum, and on this wall I also had the images from the ethnological museum, so it fitted perfectly. So I think this is also, it’s very great how you also played with the actual space and also tell stories by hanging the pictures in a specific way. So it was another layer which I really, really liked.

Exhibition view of Mardijker Photo Studio by Agan Harahap at “Hello World. Revising a Collection” at Hamburger Bahnhof – museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany, 2018.

As you already mentioned, a lot of your friends are musicians and I know you’re also a great musician, I was witnessing some really fun evenings when you played music, someone was just –it was always at the end of the evening when someone picked up a guitar, I didn’t see it before, it was somewhere in the corner, and then everybody starts singing together. This is something you would rarely experience in Berlin. So which kind of songs do you sing?

Agan: Yeah, yeah I usually sing Indonesian folk songs, or sometimes traditional Indonesian songs. It’s like a habit for – because my culture, I’m from Batak, my mother is from Ambon. Singing is an important part of their culture in Batak and Ambon. In my high school or in my college, it’s always like that, when three or four people hang around together and then we play guitar and drink beer and we can sing until morning, stuff like that. So this is very common for me and some of my friends, but sadly, singing together now is – not because of the pandemic but because electronic music is now a trend here, so it’s not that often that I see people in the corner playing guitar, it’s [something] very five or ten years ago, maybe. But me and my friends sometimes in here, we will still sing together, gather and sing together and play guitar, yeah.

Catharina: I had the impression that whenever there was a gathering in someone’s home, it ended like this. I remember the evening at Agus Suwage’s home, with a lot of people, in the end everybody was singing. I think you or Enin played the guitar and it was really fun. [laughs]

Agan: Aww, man, I was drunk at that time. [laughs]

Catharina: I think everybody was drunk. But it’s really – I really liked it. So what is the different Batak music for example and Javanese music? Can you tell a little bit about that as well?

Agan: Sure, sure. I cannot talk much about the root, it’s impossible for me. Of course there’s a difference but, if we can say in the traditional pop music, there’s a lot of difference, there’s a lot of interesting things. But usually Batak always sing – Batak people always get out from their home, they go to Jakarta, they go to everywhere else and they sing about how they miss their mama, they miss their village. It is songs about that, songs about how they struggle in the big city, yeah, it’s a kind of ballad.

But the difference in Java, it’s quite the same, it’s about love, about struggle, struggle of life. But the difference is the tone. In Batak we can say like – very loud, we can separate the voice, like ‘voice 1, voice 2, voice 3’, like a vocal group. But in Java, maybe there’s [such harmonization], but mostly only one person sings with one tone, one voice. I’ve never seen Javanese music in which the musicians sing with ‘vocal 1, vocal 2, vocal 3’, they combine [and create a harmony]. But in Batak, it’s very, very common.

Catharina: There were also some posts about the history of music, so I think what you really do is that you open up new channels for people to discuss how media, how identity, politics, history, narrations about history, and power structures are connected. Do you think that kids mostly learn about history also, besides from school, from these sources?

Agan: Yup, yup. Like I said before, people, mostly young people, they really want to – nowadays, young people really want to dig for their own identity, our identity. Like “Oh this is the old era stuff”, and they’re proud and they share it. It means “Okay, I’m more experienced than you, than [my] friends”. So that’s what I see on social media right now. I was digging the history. If you see Indonesian history accounts on Instagram, they have so many followers, and mostly they are young. So it’s interesting. Of course for me, it’s like I can manipulate it. But it’s just a small part.

Catharina: Maybe one last question, because talking about these kids, but where do you get your inspiration from? I mean, there are some series where you for example, use video games like “Call of Duty” and “Medal of Honour”. So how do you find your sources of inspiration and maybe is there something you get out of the pandemic right now? Like we were just talking about the conspiracy theories, and things like this. How do you proceed, or how do things get your attention and become sources of inspiration?

Agan: So many ways I get my inspiration. The easiest ways are by scrolling my timeline, or watching people playing games, or hearing someone talk with me. But for this pandemic, about conspiracy, I don’t get any idea about this pandemic actually, I don’t get any inspiration to make artwork from this pandemic. It’s very hard, because like I said before, I cannot – at some point I cannot believe which one is right? Because the media [keeps bombarding us with information], like “Aww man, which one is right?”, I never know. And in reality, so many people got fired from their job yeah, like my cousin, he got fired because of this pandemic, it’s so sad. I cannot make any joke about this pandemic, but I don’t know. And for the conspiracy, I think it’s like, I take it as another – If for my pleasure, behind this bad news [that we hear everyday] from the media, there’s another interesting news for me that can make me think more positively, more optimistically to get through this pandemic. Because of all the conspirations, for me, we have to be optimists to work through this pandemic.

Catharina: Okay, thank you so much for this very interesting chat. I can’t wait to see you live again, soon.

Agan: Yes soon. [laughs]

Catharina: Hopefully there will be a vaccine and some remedy so that we can travel!

Agan: Sure.

Catharina: Thank you so much.

—

Copyright and Image Credits:

© Anna-Catharina Gebbers, Agan Harahap, Art Bali, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Thomas Bruns, Singapore Art Museum, and Mizuma Gallery.

Transcribed by Marsha Tan and Theresia Irma.